-

On this page

Preliminary page

Privacy and Government

July, 2001

Prepared for:

Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner

8/133 Castlereagh Street

Sydney NSW 2000

Prepared by:

Roy Morgan Research

232 Sussex Street

Sydney NSW 2000

Prepared by:

Roy Morgan Research

232 Sussex Street

Sydney NSW 2000

Supported by:

and the Australian Taxation Office

Preface

The Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Act 2000 is due to commence on 21 December 2001. The purpose of the Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner (OFPC) is to promote an Australian culture that respects privacy. Our strategic Plan 2000 identifies four key result areas in the lead up to the commencement of the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Act. Important among these is gaining a comprehensive understanding of current community (including commonwealth government agencies) attitudes towards privacy. The research will contribute significant input into the networks we are developing with, among others, business organisations, government agencies, community groups and the health sector. Most immediately the outcomes of this research will inform the Office’s communication strategy.

Federal Government Agencies have had responsibilities under the Privacy Act since 1988. It is an opportune time for the Office to review its approach to supporting good privacy practice in government agencies, to ensure we continue to work at a strategic level. Privacy and Government will inform this review of focus and strategy as it provides a very useful picture of privacy in practice, twelve years on.

Key trends in today’s government include: on-line service delivery, fraud prevention, developing a more focussed and individual relationship with clients, and contracting of government services. These activities involve handling of personal information and can place a greater value on its collection and use. They can also have significant impact on client access to government services. It is a good sign that agencies are recognising the impact that activity in these areas may impact on privacy outcomes. I would encourage this awareness, and also encourage agencies to review privacy impacts in developing systems in these areas.

Importantly though, compliance with the Act should not be the sole concern of agencies. The OFPC research Privacy and the Community illustrates that individuals care about their privacy and these concerns are growing. In this climate, the potential impact on public relations and government generally, of getting privacy wrong, is very high.

Finally I would like to thank our Privacy Partners in this project: Australian Information Industry Association; Centrelink; Freehills; and Pricewaterhouse Coopers; and our project sponsor, the Australian Taxation Office. The generous support of these organisations enabled us to take a more thorough look at privacy, and corporate and government culture in Australia today.

Malcolm Crompton

Federal Privacy Commissioner July 2001

1. Executive summary

The Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner (OFPC) commissioned Roy Morgan Research to research the privacy knowledge, attitudes and practices of Commonwealth Government Agencies. Outcomes of this research will feed into communications, compliance and policy frameworks for the OFPC.

Roy Morgan undertook a process of qualitative and quantitative research, focusing on Privacy Contact Officers (PCOs), officers with responsibility for facilitating compliance with privacy obligations within their agency, and also operational managers, working in areas that involved the handling of personal information.

Currently, it would appear that awareness of privacy responsibilities amongst Commonwealth agency officers is high. Further, the research demonstrates that these officers confer a high importance on these responsibilities. Privacy is considered to be important area in terms of its significance to clients, staff and agency stakeholders. Overall 74% of respondents thought that privacy was very important to their agency.

More than half of the respondents (57%) ranked protection of personal information first or second in order of importance relative to the other business factors listed.

Overall 63% of respondents thought their agency had implemented privacy practices at some level. In addition, 74% indicated that their agencies had privacy guidelines and protocols in place. The areas most commonly thought to be covered by these included; personnel record management (66%), database management (59%), client service functions (56%), Internet based information policies (53%).

However, despite the high level of perceived importance and recognition that some level of implementation of privacy practices had occurred, only a little less than a third (32%) rated their agencies ‘current level of understanding / implementation of the privacy principals’ as high.

In terms of their personal knowledge of privacy matters the majority of respondents claimed to have some level of knowledge. Just under half the PCO respondents (48%) and just over half of other officers surveyed (non-PCOs 55%) felt that their privacy knowledge was actually high.

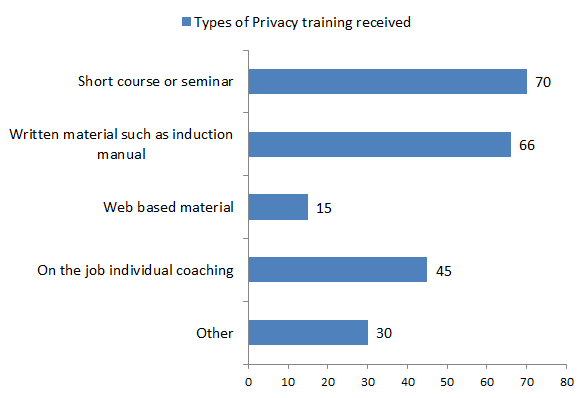

Most also reported having received some form of specific training or information on privacy laws and obligations. PCOs were more likely than other officers to have received such training (86% cf 75% for non-PCOs). The majority who had received training in privacy had attended a short course and or received written material such as via the agency’s induction or other training manuals.

Despite the high level of general knowledge of privacy issues there were some apparent gaps in the understanding about the types of information included in the term ‘personal information’. Nearly all in the survey thought that the term included a person’s name coupled with home-address, phone number and or facts such as income details, age, marital status, etc. However, far fewer people that thought ‘opinions about people’ and ‘a person’s business title, business address or phone number’ were also personal information.

PCOs reported awareness of a wide range of information flows and transfers within and between departments. Nearly four out of ten PCOs reported that agencies were involved in data-matching processes.

However, non-PCOs were much less aware of these activities taking place as part of the day to day operations and procedures in government agencies (21% Don’t know cf 5% for PCOs).

Awareness amongst PCOs of imminent change to the Privacy Act was high but non-PCOs were much less aware (86% PCOs cf 51% non-PCOs). In addition there appears to be uncertainty about what precise impact these changes might have on federal agencies.

Amongst those who were aware of the forthcoming changes, 17% of non-PCOs and 6% of PCOs did not expect any impact on federal government agencies. The 81% of respondents that were aware of the changes, expected effects on ‘government out-sourcing contracts and relationships’. Around one third of this group thought that ‘international obligations’ and ‘archiving and access to client records’ might be impacted by the legislative changes.

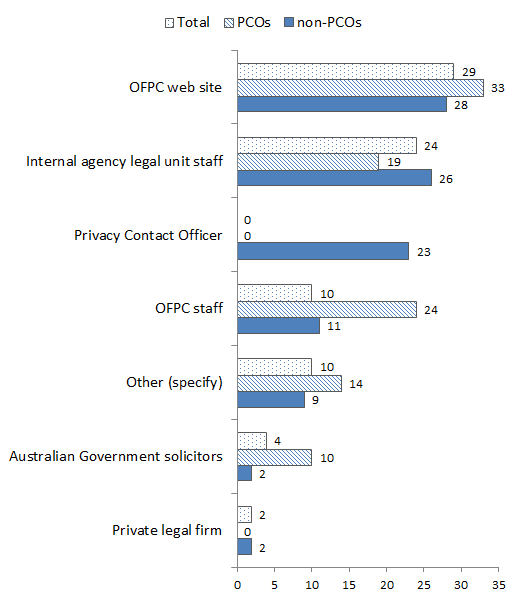

The OFPC Website was the most commonly listed (29%) main source of privacy related information for government officers. PCOs also used internal agency legal staff and OFPC Staff as key sources of advice.

Nearly one in four non-PCOs gave the agency Privacy Contact Officer as their main source of advice on privacy matters. While the incidence of PCOs as the main source of advice is encouraging, it is probably lower than might have been expected given that the non-PCOs in this survey have key roles in the management of personal information in agencies.

Raising the profile of PCOs and the advice they can provide may need to be a focus for OFPC communications, and also a strategy for individual agencies.

In addition utilisation of other forms of advice and information such as the Attorney General’s Department, private law firms, published materials and other PCOs are all currently quite low.

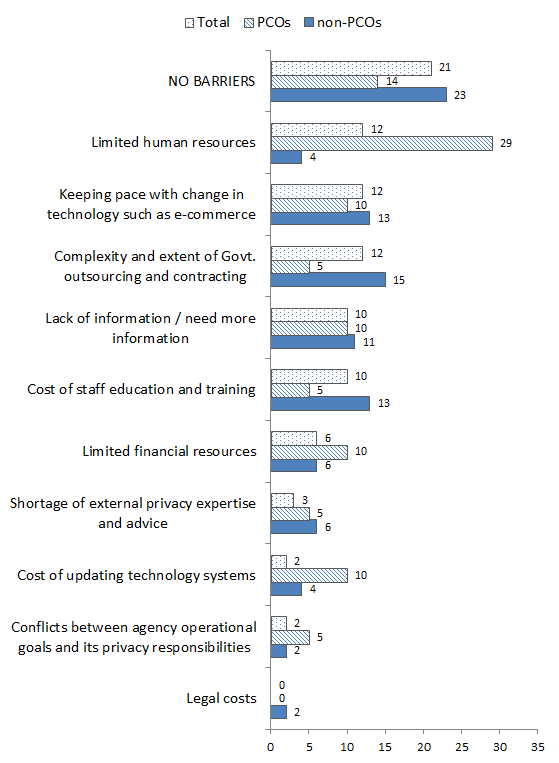

On-line service delivery was the area that created the greatest sense of unease about the capacity of agencies to implement and maintain good privacy practice. Amongst PCOs on- line service delivery was seen as by far the area of greatest challenge (48%) and ‘keeping pace with change in technology such as e-commerce’ was perceived as the main barrier to privacy best practice (29%).

PCOs were more likely to recognise barriers to good privacy than non-PCOs (only 14% of PCOs saw no barrier cf 23% of non-PCOs). The top areas seen as main barriers by non- PCOs included ‘limited human resources’ (15%), cost of staff education’ (13%), and ‘complexity of Govt. outsourcing’ (13%). While non-PCOs were less likely to see technological change as a main barrier this did top the list of other barriers nominated by this group (43%).

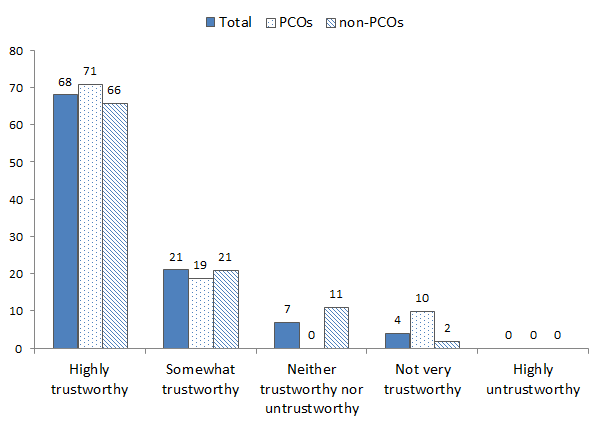

Generally government officers showed a high level of trust in their agencies’ handling of employment records and staff personal information. Over two thirds of those surveyed considered the agency where they worked to be highly trustworthy.

However, concern expressed about outsourcing of HR functions may mean that this issue could be significant to many staff in terms confidence that their personal records are well protected. Nearly one in five said they would be greatly concerned about possible HR outsourcing.

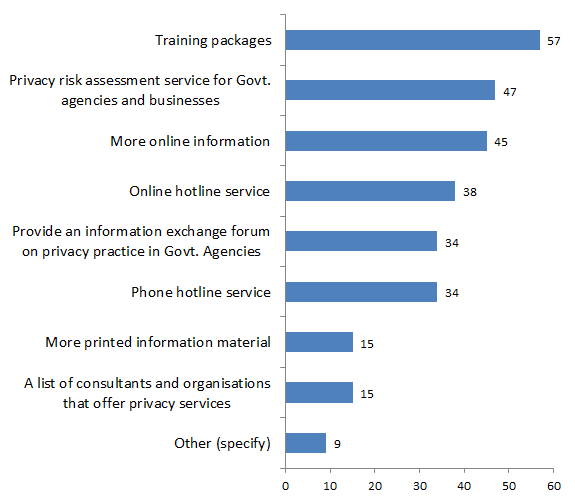

In its ongoing work with Commonwealth agencies, the OFPC may need to consider both promoting existing OFPC services to a higher degree, and also explore the development of new information services. Respondents did not exhibit a high level of knowledge about the services offered by the OFPC, and voiced some needs not currently being met by the current collection of information.

Online information and hotline services were universally supported. However, the types of information required from these services for PCOs and non-PCOs are likely to differ.

PCOs are looking for more specific and detailed information that will assist them in delivering advice to managers in the agency on particular privacy concerns. The information required would include; case studies, best practice examples and recent court decisions in the area. They also support of more effective use of the PCO network in particular mentoring or training of new PCOs by more experienced PCOs (52%).

Non-PCOs felt that training packages (57%), privacy risk assessment service (47%), more online information (45%) and online hotline service (38%) were the top four ways the OFPC could better assist agencies. Support for privacy risk assessments (an idea that was raised in the earlier qualitative research) is the result of non-PCOs feeling uncertain that processes are in place across all policy and program areas in an agency to identify practices that potentially risk breaching privacy obligations. Greater awareness of PCOs and their role and greater dialogue within agencies on these issues would also help address these concerns.

The survey results confirm that there is a high degree of concern and awareness amongst government officers in relation to privacy responsibilities and obligations. Federal agency personnel are therefore likely to be receptive to OFPC communications that address their knowledge gaps and promote useful information and alternative sources of privacy assistance across the public sector including online services, PCOs and AGs.

2. Introduction

2.1 Background

It is now 13 years since the introduction of the Federal Privacy Act 1988. The Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner (OFPC) is an independent statutory office responsible for promoting an Australian culture that respects privacy. The office currently has responsibilities under the Privacy Act for promoting protection of individuals’ personal information.

The responsibilities of the Office, however, will alter substantially in December 2001 when the Privacy Amendment Act (passed by Federal Parliament in December 2000) takes effect.

The amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 extend privacy standards to the private sector, thus requiring private sector organisations to meet specified standards for the handling of personal information.

These amendments also have implications for public sector agencies in terms of management of relationships with private sector stakeholders including; client representative organisations, suppliers, and contractors.

In January 2001 the OFPC commissioned Roy Morgan Research to undertake research to assess the current level of knowledge and implementation of privacy practices within federal government agencies.

This survey was part of a broader project to also ascertain the views of community and business in relation to privacy issues. Three separate projects: Privacy and the Community, Privacy and Business, and Privacy and Government were conducted each involving a qualitative and quantitative component. In each case the qualitative component of the project was used to inform the development of the survey design and questionnaire for the quantitative stage. A web-based survey approach was used in the quantitative element for the federal agency project.

2.2 Research objectives

The specific objectives of the survey of federal government officers were to identify:

- Current levels of knowledge, training and implementation of privacy laws and practice;

- Awareness of proposed changes to the Privacy Act and implications for government agencies;

- Perceptions and attitudes to agency privacy responsibilities and practices;

- Perceptions of challenges and barriers to best privacy practice being achieved in agencies;

- Views about agency handling of employee personal information;

- Sources of privacy information and advice; and

- Possible OFPC information services to better assist and support federal agencies in the implementation of best practice standards for privacy protection.

2.3 This report

The following report provides a descriptive analysis of results to each of the survey questions. Given the small sample achieved for this survey (68) limited sub group analysis is provided. Caution should be used when examining the results, in particular apparent differences between Privacy Contact Officers (PCOs) and other federal government agency officers (non-PCOs) on individual survey questions.

Please note the use of “cf.” throughout the report notates “compared to”.

3. Methodology

3.1 Survey approach

In response to an e-mail request from the OFPC, to CEOs of Federal Government Agencies (approximately 120), nomination for survey participants were forwarded to Roy Morgan Research, again via e-mail. Agencies provided nominations for two officers who had some responsibility for privacy policy and or practice in the agency. Usually the PCO and one other operational manager from areas such as human resources, IT, knowledge management was nominated.

Responses to the OFPC request were generally positive but slow. After two weeks e-mail addresses had been received for 112 nominated officers from 61 federal government agencies. As expected approximately half the individuals nominated by agencies were PCOs. The response level overall at this stage was about half that anticipated in pre-survey estimates by the OFPC and resulted in a smaller than expected final survey sample.

E-mail invitations to participate in the survey were sent to a total of 112 individual government officers. Overall 11 working days were allowed for survey responses. 62% of survey responses were received in the first five working days of the survey period.

3.2 Survey sample and response rate

By the time the survey was closed 68 individuals had completed the survey, which represented an effective response rate of approximately 61%. A further 16 people started but only partially completed the survey.

Slightly less than one third of the final sample were Privacy Contact officers (PCOs). The non-PCO group was comprised of HR Managers or officers as the largest group, followed by policy or program managers and other legal advisers. 18% gave a job description outside those listed. These individuals came from a wide variety of areas but Freedom of Information officer was the only job listed more than once. A full breakdown of the sample by job description is shown in Table 1.

While the response rates for the survey as indicated above were acceptable the final sample achieved was small. Consequently, the extent of analysis of the results was restricted. Although results have been reported for PCOs and non-PCOs, caution is recommended when examining differences in responses at this level for individual survey questions.

Table 1: Breakdown of Sample Respondents by role in Government Agencies

| Which best describes your current job? | % (68) |

|---|---|

| Privacy Contact Officer | 31 |

| Human Resources manager or officer | 26 |

| Information or knowledge Manager | 4 |

| IT Manager or officer (technical) | 1 |

| Legal Adviser (other than PCO) | 9 |

| Policy or program manager | 10 |

| Other | 18 |

Base: All respondents

3.3 Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was developed in close consultation with staff from the OFPC. The OFPC input was informed by discussion with a Reference Group of OFPC stakeholders. Questionnaire design was aided by the findings from the qualitative phase in terms of specific issues and attitudes to be evaluated and appropriate pre-codes to questions.

The final questionnaire consisted of 32 questions although not all respondents needed to answer all questions. A copy of the survey questionnaire is attached at Appendix 1.

After final approval, the draft questionnaire was programmed onto the web survey system and tested by Roy Morgan Research to ensure that the program logic and question sequencing was correct prior to the questionnaire going ‘live’ on the survey Website.

3.4 Web-based survey Method

Overall, a web-based methodology offered an efficient research method for this survey. Industry figures suggest that results for all web-based surveys give comparable results to other survey methods in terms of direction, interpretation and preferences[1].

Due to the high level of Internet and e-mail usage in the Australian Federal Public Service the web-based survey approach allowed for easy interviewing and data collection.

Roy Morgan Research sent out an e-mail invitation containing a hyperlink to the survey Website. Invited participants were able to click on the link in the e-mail and be instantly transferred to the survey.

The e-mail invitations contained a unique computer generated pin number. Individuals were required to enter this number to gain access to the survey on the Internet site.

To ensure participant confidentiality survey responses were never stored against respondent names, and were seen only by Roy Morgan Research and its agents. Only de-identified data was provided to the OFPC and e-mail address lists (both electronic and hard copies) were destroyed at the conclusion of the survey.

The survey web system provided complete tracking of survey responses (showing day by day numbers that had started, not started, completed and partially completed the survey). In addition, the pin number system allowed us to identify those who have not completed the survey and after a pre-determined period of time send an e-mail reminder message. Our methodology ensured no one who had completed the survey on the initial e-mailing was asked to complete it a second time.

Through this tracking mechanism Roy Morgan Research was able to monitor responses to the web survey on-line and keep the OFPC up to date with survey progress. All results were kept and collated by Roy Morgan. OFPC was provided with statistical summaries of the total results.

4. Main findings

4.1 Perceived levels of privacy knowledge

Almost all federal government agency officers that participated in the survey considered they had at least some knowledge of privacy laws and responsibilities (refer Table 2). Just under half of the PCOs and just over half of non-PCOs felt that their privacy knowledge was high (48% cf 55%).

Table 2: How would you rate your level of knowledge of privacy matters?

| Level of knowledge | Total Respondents % (68) | Privacy Contact Officers % (21) | Non PCO officers % (47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A high level of knowledge | 53 | 48 | 55 |

| Some level of knowledge | 46 | 48 | 45 |

| Very little / no knowledge | 1 | 5 | 0 |

Base: All respondents

Results suggest a logical relationship between perceived levels of privacy knowledge amongst PCOs and time in the role (although the sample at this level of disaggregation was very small). The only PCO to rate their privacy knowledge as low had only been in the role less than one year and all individuals with more than four years experience in the role (4) rated their privacy knowledge as high.

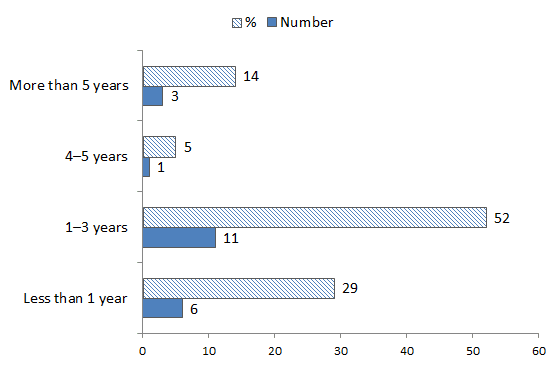

Overall the majority of PCOs (52%) in the sample had between one to three years experience in the role and 14% had been more than five years as a PCO (either with their current or another federal agency).

4.2 Privacy Training and information received

Overall the percentage of respondents that had received specific training on privacy laws and obligations was high (78% had received some specific training) and PCOs were more likely than other officers to have received such training (86% for PCOs cf 75% for Non PCOs).

Respondents that received some form of training were more likely to rate their knowledge of privacy matters as high (refer Table 3). Non-PCOs who received training were more likely than PCOs to feel confident about their knowledge of privacy matters (63% of non- PCOs who received training rating their knowledge as high cf 50% for PCOs).

It appears that many PCOs, perhaps because of their role in providing advice to others in this area, feel that they need both training and a few years experience in privacy matters before they would rate their privacy knowledge as high.

Table 3: The effect of specific training on perceived privacy knowledge

| Have you ever received specific training or information on privacy? | Yes % Total (53) | Yes % PCOs (18) | Yes % Non-PCOs (35) | No % Total (15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A high level of knowledge | 59 | 50 | 63 | 33 |

| Some level of knowledge | 42 | 50 | 37 | 60 |

| Very little / no knowledge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

The majority of those who had received training in privacy had attended a short course and or received written material such as in the agency induction or other training manuals.

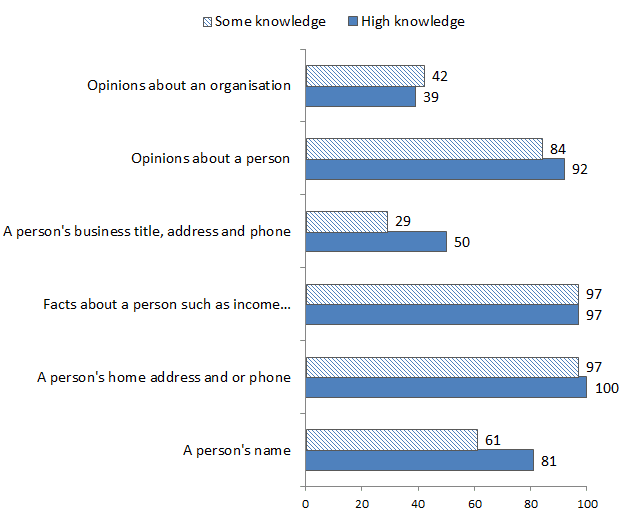

4.3 Defining ‘personal information’

When asked ‘what types of information was included in the term personal information’, 99% of respondents included a ‘person’s home address and or phone number’ and nearly as many (97%) thought that it also covered ‘facts about a person such as income details, age, marital status, etc.’

A lesser but still high percentage (88%) thought that ‘opinions or comment recorded about people’ were also personal information under the definitions used in the Privacy Act.

Far fewer people (41%) thought that ‘a person’s business title, business address or phone number’ was personal information. Most did not think that information or opinions about organisations were personal information but some thought it could be (40%).

Table 4: Respondents understanding of the term ‘personal information’

| Type of information | Total % (68) | PCOs % (21) | Non-PCOs % (47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A person’s name | 72 | 91 | 64 |

| A person’s home address an or phone… | 99 | 95 | 100 |

| Facts about a person such as income… | 97 | 100 | 96 |

| A person’s business title, address and phone | 41 | 43 | 40 |

| Opinions about a person | 88 | 91 | 87 |

| Opinions about an organisation | 40 | 5 | 55 |

Earlier qualitative research for this project, found that a significant number of people were uncertain about the application of the Privacy Act to information about individuals in the context of carrying out their business or professional roles.

PCOs recognised situations in government agencies in particular, where implied or positional consent may exist to disclose apparently personal information regarding certain individuals due to their jobs. For example, a CEO or other senior manager would be assumed to consent to their photos appearing in public material for the agency. For other staff or situations it may be less clear where an individual’s public role and their personal rights intersect. This may be why people remain divided on whether details about a person in a business role or context is ‘personal information’ in terms of obligations under the Privacy Act.

Those that considered they had a high level of privacy knowledge were more likely than those that said they only had some knowledge to include ‘information on a person’s business title, address and phone number’ in their definition of personal information (50% cf 29%). The only other area where there was some difference in the understanding between these two groups was whether a ‘person’s name’ in isolation was personal information (refer Figure 3).

Figure 3: Claimed level of privacy knowledge by percentage that included each type of information in their definition of ‘personal information’.

4.4 Sources of privacy information and advice

The OFPC Website was the main source of privacy related information for most people (refer Figure 4). 29% overall gave this as their main source of advice (33% of PCOs cf 28% of non-PCOs).

‘Other internal agency legal staff’ are the next most common source of main advice. Nearly a quarter of non-PCOs gave the agency PCO as the main source of advice on privacy matters.

Interestingly other legal staff was mentioned as the main source of advice for one in five PCOs, many of who are legal officers themselves, indicating that they perhaps routinely consult with internal colleagues before seeking any external advice.

PCOs were more than twice as likely compared with non-PCOs to give OFPC Staff as their main source of advice (24% for PCOs cf 11% for non-PCOs). PCOs were also more likely to consult the Australian Government Solicitors and a range of other sources that included mainly published privacy materials such as the OFPC’s Privacy Handbook, as published by CCH, federal privacy handbook, legislation texts and Australian Government Solicitor training materials.

Only 12% of those in the survey did not mark the OFPC as a main or other source of advice (eg. OFPC Website and /or staff). However, lack of awareness was not the reason for not seeking advice from the OFPC for this small group of respondents. Seven out of the eight people who did not seek advice from the OFPC said that they were aware of the office prior to the survey.

4.5 Awareness of proposed changes to the Privacy Act and implications for government agencies

Overall there was a high level of awareness of forthcoming changes to the Privacy Act to come into effect on 21 December 2001 but not of the likely impact of these changes.

Approximately 86% of PCOs indicated that they were aware compared with only 51% of non-PCOs officers.

Amongst those who were aware of the changes 17% of non PCOs and 6% of PCOs did not expect that it would have any impact on federal government agencies. Amongst those that were aware of the changes and expected some impact on agencies 68% thought their agency was at least prepared for these effects.

Approximately 81% of individuals that were aware of the planned changes expected effects on ‘government out-sourcing contracts and relationships’. Around one third of this group thought that ‘international obligations’ and ‘archiving and access to client records’ might be impacted by the legislative changes.

Non-PCOs were more likely to think that these changes might impact on ‘practices for sharing of information between agencies’ (29% for non-PCOs cf 17% for PCOs).

Table 5: Perceived impact of forthcoming changes to the Privacy Act

| Practice | Total % (42) | PCOs % (18) | Non-PCOs % (24) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practices for share information between agencies | 24 | 17 | 29 |

| Government out-sourcing contracts | 81 | 89 | 75 |

| International obligations and arrangements | 31 | 33 | 29 |

| Archiving and client access to records | 31 | 28 | 33 |

| Other | 12 | 11 | 13 |

| NO EFFECT on agencies | 12 | 6 | 17 |

Base: Aware of amendments

4.6 Perceptions and reporting of privacy practices in government agencies

Just under a third (32%) of respondents rated their agencies ‘current level of understanding / implementation of the privacy principals’ as high and almost all other respondents thought their agency currently had ‘some level of knowledge and implementation’ (63%).

There was no significant difference in the perceptions of PCOs and Non-PCOs about the level of privacy implementation in government agencies.

Table 6: Perceptions of current levels of privacy understanding in agencies

| Level of understanding | Total % (68) | PCOs % (21) | Non-PCOs % (47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A high level of understanding and implementation | 32 | 33 | 32 |

| Some level of understanding and implementation | 63 | 67 | 62 |

| Very little understanding and implementation | 5 | 0 | 6 |

4.6.1 Existence of privacy guidelines in agencies

Approximately 74% of respondents thought that the agency where they worked had ‘guidelines in place that outline protocols for the collection, use and protection of personal information’.

The areas most commonly thought to be covered by these guidelines included; personnel record management (66%), database management (59%), client service functions (56%), Internet based information policies (53%).

PCOs were more likely to include data-matching as being specifically covered in the guidelines for the agency (33% cf 17% for non-PCOs). On the other hand more non-PCOs thought that the guidelines included personnel record management and public relations protocols.

4.6.2 Reported participation in information sharing activities

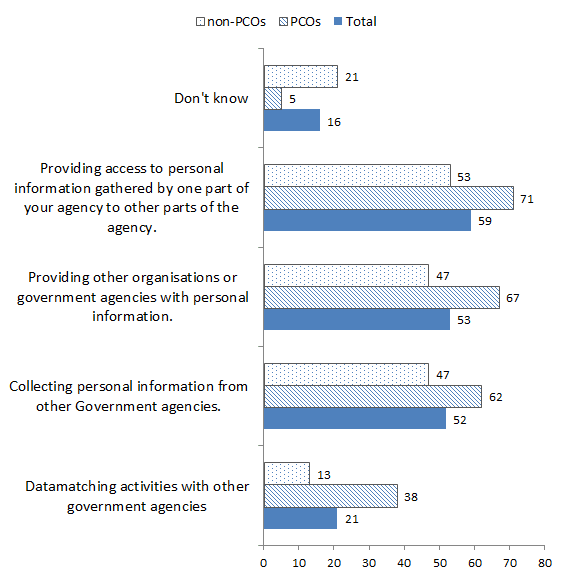

Overall PCOs showed a high level of awareness of a range of information flows and transfers within and between departments. Non-PCOs who were more likely to be unaware of any of the information sharing activities listed being undertaken by their agency (21% Don’t know cf 5% for PCOs) (refer Figure 6).

Around two thirds of PCOs reported that the agencies where they worked participated in:

- collection of personal information from other agencies (62%),

- providing other agencies with information (67%), and

- sharing of personal information within the agency (71%).

Nearly four out of ten PCOs reported that agencies were involved in data-matching processes.

Figure 5: Reported levels of sharing of personal information within and between government agencies

4.7 Perceived importance of privacy protection in government agencies

Overall 74% of respondents thought that privacy was very important to their agency and 77% thought it very important to clients of the agency.

The PCO group were slightly more likely than non-PCOs to rate privacy as very important to both the agency and its clients (81% cf 70% for the agency and 86% cf 72% for clients respectively).

In the context of a survey about privacy issues respondents ranked ‘security of personal information’ as equivalent to ‘efficient service delivery’ in terms of perceived importance to agency clients.

Overall 57% of respondents ranked protection of personal information first or second in importance relative to the other business factors listed (refer Table 7). When privacy protection was considered in the context of these other issues there was no difference in perceived importance amongst PCOs when compared with non-PCOs (57% of both groups ranked privacy protection one or two).

More PCOs (33%) ranked ‘friendly service’ first or second importance to clients and non- PCOs were more likely to rank ‘ease of access to products and services’ in the top two issues for clients.

Table 7: Perceived importance to clients of Privacy compared with other product and service factors

| Other factors | Ranked Mean scores (Out of 5 — Where 1 is most important and 5 least important) | Percentage ranking each item as 1 or 2 (ie. most and next most important) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total % | PCOs % | non-PCOs % | ||

| Protection and security of personal information | 2.44 | 57 | 57 | 57 |

| Efficient service delivery | 2.49 | 57 | 62 | 55 |

| Minimal service fees and charges | 2.94 | 21 | 14 | 23 |

| Friendly and helpful staff | 3.34 | 21 | 33 | 15 |

| Ease of access to products and services | 3.38 | 47 | 29 | 55 |

Almost all respondents considered a breach of privacy to be at least somewhat damaging to an agencies public reputation (83%) and to its relationship with the Minister (90%). More than half thought that any breach would be extremely damaging to public reputation (66%) and to the relationship with the Minister (56%).

4.7.1 Level of agreement with statements about privacy issues

In order to assess the attitudes of federal government officers to a broad range of issues relating to privacy they were asked to indicate their level of agreement with a range of statements (refer Table 8).

The responses to these scenarios are detailed below:

Generally people are more aware about privacy and their rights than a decade ago.

Almost all agreed that privacy was a more salient issue in general then it used to be (91% agreed).

Government agencies must always have a person’s consent before using or disclosing personal information.

Less than half the respondents agreed that prior consent was always required before disclosure (49%). PCOs were more likely to agree with this statement (52%) than non- PCOs (37%).

New technology is making the storage of and access to information easier but it also makes protection of information much tougher.

There was a high level of across the board agreement with this statement (88%).

An opinion about someone whether it is true or not is personal information.

PCOs were more likely to agree with this statement (81% cf 57% for non-PCOs).

The overall level of agreement on this statement (65%) is lower than the percentage of respondents that included ’opinions or comment recorded about people’ when asked the ’types of information included in the term personal information’.

This may be due to the fact that the previous question relates to opinions about clients of government agencies (and is therefore captured by the current Privacy Act) and this statement is about opinions more generally. However, it may indicate that this is an area that requires some clarification of the obligations on agencies and individuals implied when dealing with opinions recorded about individuals.

Good privacy protocols can be an impediment to providing good service to some government clients.

Level of agreement with this statement was low overall (15%). However, non-PCOs were more likely to agree with this than PCOs.

Privacy policy implementation is about risk management, with limited money and staff you can’t guarantee absolute privacy protection.

Opinion on this statement was divided overall 47% agreeing and 43% disagreeing with the statement. A similar pattern existed amongst PCOs (43% agree and 38% disagree) and non-PCOs (49% agree and 43% disagreed). This split may suggest a division between the ‘idealists’ (who would strive for absolute privacy at all times and at whatever costs) and pragmatists (who can accept a concept of affordable privacy standards).

At the end of the day government can outsource functions but not responsibility

Once again this statement generated almost universal agreement amongst respondents overall (91%) and with PCOs (91%) and non-PCOs (92%).

Government clients can always trust the government’s use and handling of their information

Only a very small minority could agree with this (6%). About a quarter was neutral (24%) and the majority disagreed (68%). This may be a natural cynicism that says that no organisation can always be trusted despite that fact that they felt that government agencies consider privacy of personal information to be an important issue (refer Section 4.7).

Table 8: Level of agreement with statements about privacy issues

| Agreement (strongly agree/agree) with… | Total % (68) | PCOs % (21) | Non-PCOs % (47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generally people are more aware about privacy and their rights than a decade ago | 91 | 95 | 89 |

| Government agencies must always have a person’s consent before using or disclosing personal information. | 49 | 52 | 37 |

| New technology is making the storage of and access to information easier but it also makes protection of information much tougher. | 88 | 90 | 87 |

| An opinion about someone whether it is true or not is personal information. | 65 | 81 | 57 |

| Good privacy protocols can be an impediment to providing good service to some government clients. | 15 | 10 | 17 |

| Privacy policy implementation is about risk management, with limited money and staff you can’t guarantee absolute privacy protection. | 47 | 43 | 49 |

| At the end of the day government can outsource functions but not responsibility | 91 | 91 | 92 |

| Government clients can always trust the government’s use and handling of their information | 6 | 0 | 9 |

4.7.2 Level of concern about scenarios involving handling of personal information

Respondents were asked to consider a number of scenarios that might occur in government agencies and involved the handling of personal information. For almost two thirds of people all three scenarios would be a source of great concern if each occurred in the agency where they worked (refer Table 9). There was no difference in the level of concern felt about these scenarios between PCO and non-PCOs.

Table 9: Percentage greatly concern about scenarios involving handling of personal information

| Would have great concern about these situations and practices if each occurred in the agency | Total % (68) | PCOs % (21) | non-PCOs % (47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| An officer discovers that a colleague in a regional office is providing staff in another government agency with regular access to client data to assist with locating individuals that may be connected with a crime. | 69 | 67 | 70 |

| A colleague tells you that they have given medical record information to a relative of an aging client to assist the relative in accessing benefits on the client’s behalf. The relative did not have the client’s power of attorney. | 75 | 86 | 70 |

| At morning tea a colleague tells you a funny story about an incident that occurred during a client’s recent hospital visit. The colleague read about this on the client’s file. | 68 | 67 | 68 |

4.8 Perceptions of challenges and barriers to best privacy practice in government agencies

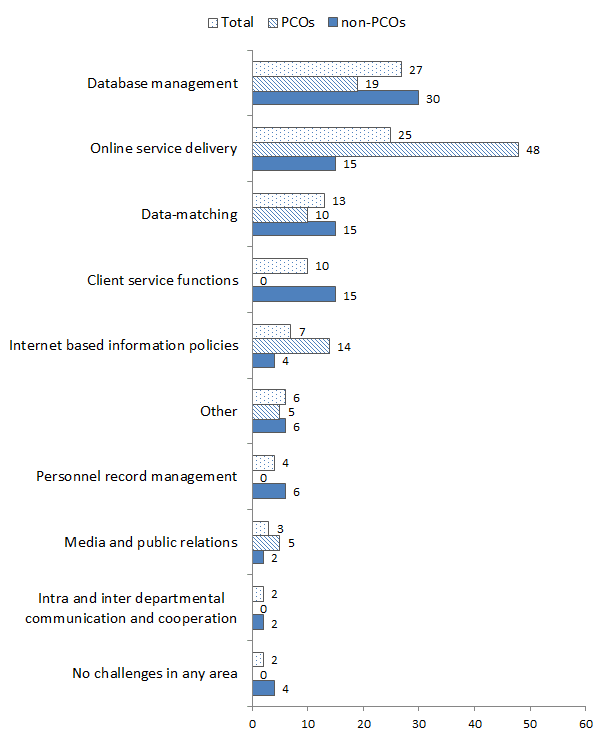

Overall database management (27%) and on-line service delivery (25%) were the areas that federal government officers considered as providing the greatest challenge for achieving privacy best practice in their agencies.

Amongst PCOs on-line service delivery was seen as by far the area of greatest challenge (48%) to good privacy. Non-PCOs were more likely to see more general database management as being the primary area of challenge (refer Figure 6).

When asked about other challenges PCO were more likely to indicate client service functions (62%) and database management (48%). More non-PCOs than PCOs gave on- line service delivery (45%), intra and inter departmental communication and cooperation (43%) and personnel record management (40%) as the other key areas representing challenges.

Figure 6: Area of business activity given as the greatest challenge for agencies with privacy responsibilities (percentage of sample)

Despite the high perception of challenges that needed to be addressed by agencies in the area of privacy (only 2% thought there were no challenges for agencies) one in five respondents did not name a primary resource or knowledge barrier to achieving best privacy practice. However, PCOs were more likely to recognise barriers than non-PCOs (only 14% of PCOs saw no barrier cf 23% of non-PCOs)

More PCOs considered that ‘keeping pace with change in technology such as e-commerce’ is the main barrier to privacy best practice. This is consistent with one of the findings of the earlier qualitative research namely that;

’Some PCOs thought that their current skills (mostly legal training) were only part of what will be needed in the future. Privacy and FIO management will need to be part of the overall knowledge management functions of agencies. IT and information management knowledge will be as critical as legal understanding in developing best practice approaches for privacy in the new millennium.’

When asked about other challenges PCOs included factors such as ‘complexity of Govt. outsourcing’ (43%), ’costs of staff training and education (38%), cost of updating technology (29%) and ‘conflicts between agency and operational goals and its privacy responsibilities’ (29%).

Although non-PCOs tended to see less barriers overall, those that did nominate a main barrier saw resource issues as key to better implementation and standards for privacy practice in agencies. The top areas seen as main barriers by this group included ‘limited human resources’ (15%), cost of staff education’ (13%), and ‘complexity of Govt. outsourcing’ (13%).

While non-PCOs were less likely to see technological change as a main barrier this did top the list of other barriers nominated by this group (43%).

4.9 Views about agency handling of employee personal information

Over two thirds of the federal agency officers in the survey considered the agency where they worked to be highly trustworthy in relation to the handling of employment records and staff personal information. On the other end of the scale no one consider their agency to be highly untrustworthy (refer Figure 8).

Figure 8: Trust in agencies handling of employment records and staff personal information

4.9.1 Levels of concern about uses of staff personal information

In order gauge individual expectations of the standards of protection that should apply to staff personal information, they were asked to rate their level of concern about two specific scenarios relating to the handling of their personal information at work.

The first scenario involved the use of staff information in connection with a social event in the agency:

- Scenario 1: ‘In some agencies it is customary for staff members to ask for information from employment records such as date of birth, work commencement date and work history so that they can make speeches at farewell or retirement events. HR staff and colleagues routinely provide this information.’

This scenario is based on real experiences (discussed in the qualitative research) and is one that most would feel could occur in any organisation. So it is of interest that six out of ten individuals reported that they would find this situation of concern if it happened in their agency.

Although this was only one scenario and the level of concern expressed may be somewhat overstated due to the research context (ie. a privacy survey), the result does suggest that individuals can identify common situations in the work environment that may in fact involve an intrusion on individual privacy. It would seem that tolerance of these activities might be a matter of organisational culture rather than a failure to understand the literal obligations of privacy legislation.

4.9.1 Levels of concern about uses of staff personal information

In order gauge individual expectations of the standards of protection that should apply to staff personal information, they were asked to rate their level of concern about two specific scenarios relating to the handling of their personal information at work.

The first scenario involved the use of staff information in connection with a social event in the agency:

- Scenario 1: ‘In some agencies it is customary for staff members to ask for information from employment records such as date of birth, work commencement date and work history so that they can make speeches at farewell or retirement events. HR staff and colleagues routinely provide this information.’

This scenario is based on real experiences (discussed in the qualitative research) and is one that most would feel could occur in any organisation. So it is of interest that six out of ten individuals reported that they would find this situation of concern if it happened in their agency.

Although this was only one scenario and the level of concern expressed may be somewhat overstated due to the research context (ie. a privacy survey), the result does suggest that individuals can identify common situations in the work environment that may in fact involve an intrusion on individual privacy. It would seem that tolerance of these activities might be a matter of organisational culture rather than a failure to understand the literal obligations of privacy legislation.

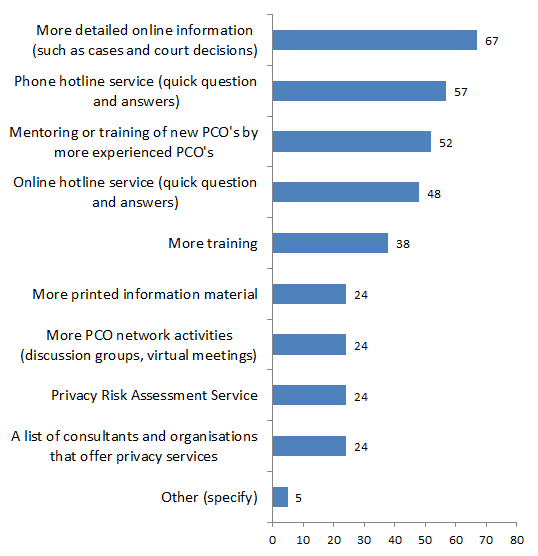

Figure 10: Views of non-PCOs about ways the OFPC could better assist agencies

PCOs also supported the idea of more online information on privacy such as cases and court decisions (67%). Other suggestions supported by around half the PCOs surveyed included; a phone hotline service (57%), mentoring or training of new PCOs by more experienced PCOs (52%) and an online hotline service (48%).

Appendix 1: Privacy Govt. Agency Quantitative Web Survey Questionnaire

Welcome to the Roy Morgan Research Web survey site and THANK YOU for agreeing to participate in this important survey on Privacy in Australia.

This research is being undertaken on behalf the Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner (OFPC) by Roy Morgan Research, the people who conduct the Morgan Gallup poll.

How to Answer

Please read all instructions and information carefully. To mark your response or responses to each question simply mouse click on the button next to your chosen answer/s.

You may also be asked to provide a short written response or clarification to some questions. Please type your answer in the space provided under or near each question.

Help messages and instructions are provided to guide you through the survey. For example the survey system will not accept multiple responses where they are not required and will not let you continue until the current question has been answered.

Should you be called away while carrying out the survey your responses will be automatically saved when you leave the survey site. When you return to the site you will be able to continue answering the remainder of the questionnaire.

1. Which of the following best describes your current job?

- Privacy Contact Officer (PCO)

- HR Manager or officer

- Information or knowledge manager

- IT Manager or officer (technical)

- Legal adviser (other than PCO)

- Policy or program manager

- Other (Please specify)

2. If PCO in Q1 ask>How long have you been a PCO (include time in your current agency plus any time in this role elsewhere)?

- Less than one year

- One to three years

- Four to five years

- More than five years

3. All other answers to Q1 ask> Does your organisation have a nominated staff member to oversee privacy issues relating to the collection, transfer and use of clients and staff personal information?

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

4. How would you rate your level of knowledge of privacy matters, in relation to managing or handling personal information, as part of your work?

- A high level of knowledge

- Some knowledge

- Very little knowledge

- No knowledge at all

5. Does your agency have guidelines in place, that outline protocols for the collection, use and protection/storage of personal information?

- Yes

- No (skip to Q7)

- Don’t know (skip to Q7)

6. Which of the following areas do you think are specifically covered by these guidelines?

Please mark as many or as few as you think applies.

- Client service functions

- Database management

- Internet based information policies

- Online service delivery

- Data-matching

- Personnel record management

- Intra and inter departmental communication and cooperation

- Media and public relations

- None of the above

- Other (specify)

7. Federal privacy legislation outlines procedures for the collection, use and storage of personal information.

What sort of information handled by your agency do you understand the term ‘personal information’ to include?

Please mark as many as or as few as you think applies.

- A person’s name

- A person’s home address and / or phone number

- Facts about a person such as, income details, age, marital status, etc.

- Information such as a person’s business title, business address and phone number.

- Opinions or comments recorded about people that the agency deals with.

- Opinions or comments recorded about organisations that the agency deals with.

- None of the above

8. Have you ever received specific training or information materials on privacy obligations, laws and regulations governing federal government agencies?

- Yes

- No (Skip to Q10)

9. What types of privacy training or information material have you received?

- Short course or seminar

- Written material such as in the agency induction manual, etc.

- Web based tutorial or reference material

- On the job individual coaching or instruction

- Other (please specify)

10. There are a number of amendments to federal privacy laws that will come into effect on the 21st of December this year. Are you aware of what these are?

- Yes

- No (Skip to Q12)

11. To your knowledge what areas of your agency’s activities will be effected by these changes, if any?

Please mark as many or as few areas as you think applies.

- Practices for sharing of information between government agencies

- Government outsourcing contracts and relationships

- International obligations and arrangements with other overseas government agencies

- Archiving and client access to government records in some areas.

- Other (specify)

- No effect on government agencies at all. (skip to Q13)

12. How well prepared do you think your agency is for the impact of forthcoming changes to the Privacy Act?

- Well prepared

- Prepared

- Not at all prepared

- Don’t know

13. In your view, how important an issue is protection of personal information in your agency?

- Very important

- Important

- Neither important or not important

- Not very important

- Not at all important

14. In your view, how important an issue is protection of personal information to the clients and stakeholders of your agency?

- Very important

- Important

- Neither important or not important

- Not very important

- Not at all important

15. In your view, how important are the following to clients of your agency?

Please rank from 1 to 5 where:

1= MOST IMPORTANT ---> ----> -----> 5 = Least Important

- Ease of access to products or services

- Efficiency of service delivery

- Friendly and helpful staff

- Protection and security of personal

information - Minimal service fees or charges

16. How damaging could publicity concerning a breach of customer privacy be to your agency’s PUBLIC REPUTATION?

- Extremely damaging

- Somewhat damaging

- Neither damaging or not damaging

- Not very damaging

- Not at all damaging

17. How damaging could publicity concerning a breach of customer privacy be to your agency’s RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR MINISTER?

- Extremely damaging

- Somewhat damaging

- Neither damaging or not damaging

- Not very damaging

- Not at all damaging

It is thirteen years since the implementation of the Federal Privacy Act.

18. How would you rate the current level of understanding and implementation of the privacy principles in your agency?

- A high level of understanding and implementation

- Some level understanding and implementation

- Very little understanding and implementation

- No understanding or implementation.

19. How would you rate your level of concern about the following situations and practices if each were to occur in your agency?

| Situation | Great Concern | Some concern | Neither great or little concern | Little concern | No concern at all |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An officer discovers that a colleague in a regional office is providing staff in another government agency with regular access to client data to assist with locating individuals that may be connected with a crime. | |||||

| A colleague tells you that they have given medical record information to a relative of an aging client to assist the relative in accessing benefits on the client’s behalf. The relative did not have the client’s power of attorney. | |||||

| At morning tea a colleague tells you a funny story about an incident that occurred during a client’s recent hospital visit. The colleague read about this on the client’s file. |

20. Which area of government business activity if any do you believe, represents the GREATEST CHALLENGE for Government agencies with privacy responsibilities?

- Client Service functions

- Database management

- Internet based information policies

- Online service delivery

- Data-matching

- Personnel record management

- Intra and inter departmental communication and cooperation

- Media and public relations

- Other

- No challenges in any area (skip to 23)

21. Why do you think this area is the greatest challenge?

22. Which OTHER AREAS, if any are likely to represent significant challenges for Government agencies with privacy responsibilities?

- Client Service functions

- Database management

- Internet based information policies

- Online service delivery

- Data-matching

- Personnel record management

- Intra and inter departmental communication and cooperation

- Media and public relations

- Other

- No other challenges

23. Please indicate whether you agree or disagree with each of the following statements: (We are after your personal views)

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Can’t say |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generally people are more aware about privacy and their rights than a decade ago | ||||||

| Government agencies must always have a person’s consent before using or disclosing personal information. | ||||||

| New technology is making the storage of and access to information easier but it also makes protection of information much tougher. | ||||||

| An opinion about someone whether it is true or not is personal information. | ||||||

| Good privacy protocols can be an impediment to providing good service to some government clients. | ||||||

| Privacy policy implementation is about risk management, with limited money and staff you can’t guarantee absolute privacy protection. | ||||||

| At the end of the day government can outsource functions but not responsibility | ||||||

| Government clients can always trust the government’s use and handling of their information |

24. Which of the following information sharing activities does your agency participate in?

- Datamatching activities with other government agencies

- Collecting personal information from other organisations or Government agencies.

- Providing other organisations or government agencies with personal information.

- Providing access to personal information gathered by one part of your agency to other parts of the agency.

- Don’t Know

25. What do you believe is the main barrier, if any, for your agency in terms of achieving and maintaining privacy best practice?

- Lack of information / need more information

- Cost of staff education and training

- Cost of updating technology systems

- Legal costs

- Conflicts between agency operational goals and its privacy responsibilities.

- Shortage of external privacy expertise and advice

- Keeping pace with change in technology such as e-commerce.

- Complexity and extent of Govt. outsourcing and contracting

- Limited financial resources

- Limited human resources

- NO BARRIERS (skip next question)

- Other (specify)

26. What other barriers if any, do you believe there are for your agency in achieving and maintaining privacy best practice?

- Lack of information / need more information

- Cost of staff education and training

- Cost of updating technology systems

- Legal costs

- Conflicts between agency operational goals and its privacy responsibilities.

- Shortage of external privacy expertise and advice

- Keeping pace with change in technology such as e-commerce.

- Complexity and extent of Govt. outsourcing and contracting

- Limited financial resources

- Limited human resources

- No other Barriers

- Other(specify)

Now thinking about protection of your personal employment records and information at work.

27. How trustworthy would you say your agency is when it comes to protection or use of your employment records and personal information?

- Highly trustworthy

- Somewhat trustworthy

- Neither trustworthy nor untrustworthy

- Not very trustworthy

- Highly untrustworthy

28. How would you rate your level of concern about the following situations and practices if each were to occur in your agency?

| Situation | Great Concern | Some concern | Neither great or little concern | Little concern | No concern at all |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In some agencies it is customary for staff members to ask for information from employment records such as date of birth, work commencement date and work history so that they can make speeches at farewell or retirement events. HR staff and colleagues routinely provide this information. | |||||

| An e-mail is sent to all staff in your agency stating that HR functions are going to be market tested as the first step towards planned outsourcing of these functions. |

29. What or who would be your main source of information and advice on privacy matters connected with your job?

- Internal agency legal unit staff

- Privacy Contact officer(ask only for non PCO participants as answered in Q1)

- Private Legal firm

- Australian Government Solicitors

- OFPC Web site

- OFPC staff

- Other (specify)

30. What OTHER SOURCES of privacy information and advice might you also use?

- Internal agency legal unit staff

- Privacy Contact officer(ask only for non PCO participants as answered in Q1)

- Private Legal firm

- Australian Government Solicitors

- Privacy Commission Web site

- Privacy Commission staff

- Other

If did not mark Privacy Commission Website or staff in Q29 or 30 then ask Q31, otherwise go to Q32 a or b>

The Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner exists to uphold privacy laws and to investigate any complaints made with regard to privacy breaches.

31. Were you aware of the Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner before being invited to complete this survey?

- Yes

- No

32. A ASK ONLY FOR NON PCO’s In what ways, if any, do you think the Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner could better assist your agency improve its privacy practices?

- More online information

- More printed information material

- Training Packages

- Provide an information exchange forum on privacy practice in Govt. agencies

- Phone Hotline Service

- Online Hotline Service

- Privacy Risk Assessment Service for Govt. agencies and businesses

- A list of consultants and organisations that offer privacy services

- Other (specify)

32. B ASK ONLY FOR PCO’s> In what ways, if any, do you think the Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner could better assist and support you in your role as PCO for your agency?

- More detailed online information (such as cases and court decisions)

- More printed information material

- More Training

- Phone Hotline Service (quick question and answers)

- Online Hotline Service (quick question and answers)

- More PCO network activities (discussion groups, virtual meetings)

- Privacy Risk Assessment Service

- Mentoring or training of new PCO’s by more experienced PCO’s

- A list of consultants and organisations that offer privacy services

- Other (specify)

Thank you for your cooperation with this survey.

If you would like more information on privacy laws you can call the Privacy Office Hotline on 1300 363 992 or obtain further details on their web site at www.privacy.gov.au.

Long text descriptions

Figure 1: Percentage and number of PCOs by time in the role.

Figure 1 is a column chart showing the time PCOs have had in the role. The majority (52%) had been in the role for 1–3 years. The percentages and numbers are as follows:

| Time | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | 6 | 29 |

| 1–3 years | 11 | 52 |

| 4–5 years | 1 | 5 |

| More than 5 years | 3 | 14 |

Figure 2: Types of privacy training and Information received

Figure 2 is a column chart showing the types of privacy training and information received. The most common type was Short course or seminar, at 70%. The full list by decreasing order of frequency is as follows:

- Short course or seminar: 70%

- Written material such as induction manual: 66%

- On the job individual coaching: 45%

- Other: 30%

- Web based material: 15%

Figure 3: Claimed level of privacy knowledge by percentage that included each type of information in their definition of ‘personal information’.

Figure 3 is a column chart showing the types of information respondents included in their definition of ‘personal information’, comparing whether the respondents claimed some knowledge or high knowledge. The most common type of information for both levels of knowledge was A person’s home address and or phone.

| Type of information | High knowledge % | Some knowledge % |

|---|---|---|

| A person’s name | 81 | 61 |

| A person’s home address and or phone | 100 | 97 |

| Facts about a person such as income… | 97 | 97 |

| A person’s business title, address and phone | 50 | 29 |

| Opinions about a person | 92 | 84 |

| Opinions about an organisation | 39 | 42 |

Figure 4: Main sources of advice on privacy matters

Figure 4 is a column chart which shows the main sources of advice on privacy matters for PCOs and non-PCOs.

| Source of advice | non-PCOs % | PCOs % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|

| OFPC web site | 28 | 33 | 29 |

| Internal agency legal unit staff | 26 | 19 | 24 |

| Privacy Contact Officer | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| OFPC staff | 11 | 24 | 10 |

| Other (specify) | 9 | 14 | 10 |

| Australian Government solicitors | 2 | 10 | 4 |

| Private legal firm | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Figure 5: Reported levels of sharing of personal information within and between government agencies

Figure 5 is a column chart that shows reported levels of sharing of personal information within and between government agencies, comparing responses from non-PCOs and PCOs.

| Level of sharing | non-PCOs % | PCOs % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datamatching activities with other government agencies | 13 | 38 | 21 |

| Collecting personal information from other Government agencies. | 47 | 62 | 52 |

| Providing other organisations or government agencies with personal information. | 47 | 67 | 53 |

| Providing access to personal information gathered by one part of your agency to other parts of the agency. | 53 | 71 | 59 |

| Don’t know | 21 | 5 | 16 |

Figure 6: Area of business activity given as the greatest challenge for agencies with privacy responsibilities (percentage of sample)

Figure 6 is a column chart showing which areas of business activities were reported as the greatest challenge for agencies with privacy responsibilities, comparing responses from PCOs and non-PCOs. The greatest challenge reported by PCOs was online service delivery at 48%, while for non-PCOs it was database management at 30%.

| Area of business activity | non-PCOs % | PCOs % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database management | 30 | 19 | 27 |

| Online service delivery | 15 | 48 | 25 |

| Data-matching | 15 | 10 | 13 |

| Client service functions | 15 | 0 | 10 |

| Internet based information policies | 4 | 14 | 7 |

| Other | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Personnel record management | 6 | 0 | 4 |

| Media and public relations | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Intra and inter departmental communication and cooperation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| No challenges in any area | 4 | 0 | 2 |

Figure 7: Perceived Main Barriers to Privacy Best Practice

Figure 7 is a column chart showing what the perceived main barriers to privacy best practice were, comparing responses from PCOs and non-PCOs. PCOs perceived limited human resources to be the main barrier (29%) while non-PCOs reported no barriers (23%).

| Perceived barrier | non-PCOs % | PCOs % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO BARRIERS | 23 | 14 | 21 |

| Limited human resources | 4 | 29 | 12 |

| Keeping pace with change in technology such as e-commerce | 13 | 10 | 12 |

| Complexity and extent of Govt. outsourcing and contracting | 15 | 5 | 12 |

| Lack of information / need more information | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| Cost of staff education and training | 13 | 5 | 10 |

| Limited financial resources | 6 | 10 | 6 |

| Shortage of external privacy expertise and advice | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| Cost of updating technology systems | 4 | 10 | 2 |

| Conflicts between agency operational goals and its privacy responsibilities | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Legal costs | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Figure 8: Trust in agencies handling of employment records and staff personal information

Figure 8 is a bar chart showing the levels of trust the respondents had in agencies handling employment records and staff personal information, comparing responses from PCOs and non-PCOs. The majority of all respondents considered their agency to be highly trustworthy (68%).

| Level of trust | Total % | PCOs % | non-PCOs % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly trustworthy | 68 | 71 | 66 |

| Somewhat trustworthy | 21 | 19 | 21 |

| Neither trustworthy nor untrustworthy | 7 | 0 | 11 |

| Not very trustworthy | 4 | 10 | 2 |

| Highly untrustworthy | 0 | 0 | 0 |

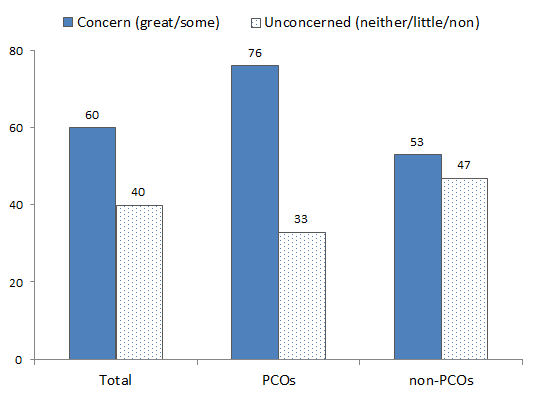

Figure 9: Concern about use of personal information in speeches

Figure 9 is a column chart showing the level of concern respondents had to the following scenario: ‘In some agencies it is customary for staff members to ask for information from employment records such as date of birth, work commencement date and work history so that they can make speeches at farewell or retirement events. HR staff and colleagues routinely provide this information.’ It compares responses from PCOs and non-PCOs. The majority of respondents found it more concerning than unconcerning (60% compared to 40%) but PCOs were far more concerned (76%) than non-PCOs (53%).

| Level of concern | Total % | PCOs % | non-PCOs % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concern (great/some) | 60 | 76 | 53 |

| Unconcerned (neither/little/non) | 40 | 33 | 47 |

Figure 10: Views of non-PCOs about ways the OFPC could better assist agencies

Figure 10 is a bar chart showing the ways that non-PCOs thought the OFPC could better assist agencies. The most popular way was Training packages at 57%. The full list is as follows:

- Training packages: 57%

- Privacy risk assessment service for Govt. agencies and businesses: 47%

- More online information: 45%

- Online hotline service: 38%

- Provide an information exchange forum on privacy practice in Govt. Agencies: 34%

- Phone hotline service: 34%

- More printed information material: 15%

- A list of consultants and organisations that offer privacy services: 15%

- Other (specify): 9%

Figure 11: Ways the OFPC could better assist PCOs

Figure 11 is a bar chart showing the ways that PCOs thought the OFPC could better assist them. The most popular way was More detailed online information (such as cases and court decisions) at 67%. The full list is as follows:

- More detailed online information (such as cases and court decisions): 67%

- Phone hotline service (quick question and answers): 57%

- Mentoring or training of new PCO’s by more experienced PCO’s: 52%

- Online hotline service (quick question and answers): 48%

- More training: 38%

- More printed information material: 24%

- More PCO network activities (discussion groups, virtual meetings): 24%

- Privacy Risk Assessment Service: 24%

- A list of consultants and organisations that offer privacy services: 24%

- Other (specify): 5%

Footnote

[1] Market Research Society of Australia – Internet Research workshop June 2001.