-

On this page

Assessment undertaken: October 2017

Draft report issued: May 2018

Final report issued: September 2019

Part 1: Executive summary

1.1 This report outlines the findings of an assessment of the Department of Human Services’ (DHS) Non-Employment Income Data Matching (NEIDM) program, undertaken by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC).

1.2 The scope of this assessment was limited to the consideration of DHS’s handling of personal information for the purposes of the NEIDM program under Australian Privacy Principle (APP) 1.2 (open and transparent management of personal information), APP 3 (collection of solicited personal information) and APP 5 (notification of collection of personal information).

1.3 The assessment found that DHS has taken steps to build privacy awareness and risk management into their data matching processes. Specifically, DHS has a generally robust privacy impact assessment process that assists with the early detection of privacy risks.

1.4 However, the OAIC identified potential risks associated with the NEIDM program and has made four recommendations to address these risks and improve overall privacy management within DHS. The OAIC recommended that DHS:

- develops and implements internal policies related to the handling of personal information, specifically:

- a Privacy Management Plan (PMP) that sets out its privacy goals and targets

- an effective data breach response plan that guides staff to take appropriate actions and follow procedures in the event of a breach.

- reviews the NEIDM program protocol to identify what additional information should be included, in accordance with the APPs and the OAIC’s Guidelines on Data Matching in Australian Government Administration. Specifically, DHS should expand on the use of business rules and filtering within the program protocol. Should these details be considered sensitive in nature, the OAIC suggests that DHS consider also creating an internal, more detailed version of the protocol for auditing, monitoring and quality control purposes.

- develops a process for monitoring the implementation of privacy impact assessment (PIA) recommendations, in particular the recommendations from the NEIDM PIA to ensure their relevance to the current NEIDM operating processes. This could involve the process currently being developed by the DHS privacy team.

- ensures the requirements of its operational privacy policy, including requirements for business areas to conduct twice-yearly audit checks of information in the public-facing APP 1 privacy policy, are followed.

Part 2: Introduction

Background

2.1 The Department of Human Services (DHS) undertakes compliance activities through data matching programs to ensure ongoing eligibility entitlements and to maintain the integrity of customer payments and services.

2.2 Data matching is the bringing together of at least two data sets that contain personal information, and that come from different sources, and the comparison of those data sets with the intention of producing a match.[1] Agencies must comply with the Privacy Act 1988 and this encompasses the data-matching related activities that they undertake.

2.3 The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has been allocated funding to provide regulatory oversight of privacy implications arising from DHS’s increasing data matching activities using new methodologies, for the period 1 January 2016 to 30 June 2019. This funding is part of the ‘Enhanced Welfare Payment Integrity – non-employment income data matching’ 2015-16 budget measure.

2.4 DHS conducts a number of data matching programs to determine whether a customer’s entitlement payment or debts are accurate based on the type of income customers earn or the payments they receive.

2.5 The Non-Employment Income Data Matching (NEIDM) program focuses on identifying discrepancies between the non-employment income reported by customers to Centrelink and to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).[2] It replaced the previous tax return income matching process adopted by the DHS set out in the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 (DMP Act). The purpose of the NEIDM program is to identify non-compliant customers requiring administrative or investigative action.

Overview of the NEIDM program

2.6 In the 2015-16 mid-year economic and fiscal outlook, the Australian Government announced the Non-Employment Income Data Matching program.[3]

2.7 This program addresses non-declared and under-declared income. While originally intended to eventually utilise an online compliance capability as the main communication and assessment platform, DHS has deferred this development due to operational issues. Customers continue to receive a letter requesting them to contact Centrelink and a staff member then works with the customer to confirm, or if appropriate, correct the discrepancy identified during the data matching process.

NEIDM program - information flows

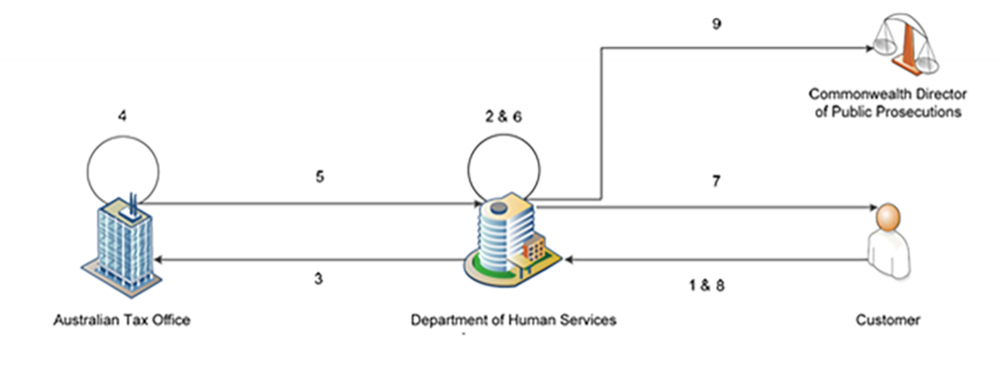

2.8 The diagram and table below outline the data flows between entities involved in the NEIDM data matching program, as well as how a DHS customer’s personal information is handled internally by DHS.

Figure 1 Map of information flow in the NEIDM process (Source: Non-Employment Income Data Matching Process PIA, page 6).

Flow | Key process | Description |

|---|---|---|

1 | Collection (DHS) | The customer provides information to DHS in order to receive various services and payments via hard copy application forms such as the Income and Assets declaration or the Claim for Disability Support Pension form. Information can also be provided over the phone or online. This initial collection includes, but is not limited to full name, address, marital status, living arrangements, and a declaration of assets and income. Depending on the payment or services the customer receives, they may also need to provide sensitive information such as their medical history to ensure their entitlements are accurately calculated by DHS. |

2 | Use (DHS) | This information is placed in a customer file, and this file can potentially be used for a number of data analytics purposes across DHS (see ‘Secondary use of customer data’ section). |

3 | Disclosure (DHS) | DHS provides the ATO with a request data file containing the following customer information for identity matching:

DHS provides this information for customers who have received entitlement payment, including partners of those customers. DHS makes this request twice a year to the ATO. It is estimated that DHS requests between 4,000,000 and 6,000,000 customer files per year from the ATO. |

4 | Collection/Use (ATO) | The ATO uses the customer’s personal information in the data file to identity match to any data that the ATO holds about that customer. While DHS is aware that proprietary software is used to conduct this process, it is not aware of the specific process used within the ATO to match the DHS file to the ATO income data. The ATO assigns a confidence level to the quality of the data to indicate to DHS the accuracy of the match. This is discussed further in Part 3 of the report. This assessment report does not consider the ATO’s personal information handling practices. |

5 | Collection (DHS) | Once identities have been matched, the ATO sends a response data file to DHS, which contains the customer’s file with their:

|

6 | Use (DHS) | DHS reviews the matched data in the response data file against its own records to identify discrepancies in the income declared by the customer. DHS then applies filters to the matched pool of data to narrow the number of potential discrepancies for consideration in the next stage. Some filters are embedded in the process and are routinely applied to the records of customers with known vulnerabilities. DHS also applies ‘live’ filtering, which is selectively and temporarily applied to individuals, depending on their circumstances, for compassionate reasons. For example, filtering records of individuals who reside in locations that have been declared natural disasters areas or for bereavement reasons. DHS stores the income tax return data set and PAYG data set in its SAP HANA system, an in-memory platform used for processing high volumes of data. |

7 | Collection (DHS) | In circumstances where DHS is considering undertaking compliance activity (e.g. debt recovery) with a customer, DHS may contact a customer via letter or telephone to request further information and provide the customer with their income tax return information. DHS sends letters to a customer’s last known address or sends a myGov notification, in the form of an email notifying the customer to log into their account to view a secure online letter, to initiate the compliance intervention process. |

8 | Collection (DHS) | The customer is asked to confirm the accuracy of the income tax return information or to update it to ensure the DHS records are accurate. The additional information provided by customers is a part of the compliance intervention process. |

9 | Disclosure (DHS) | Where fraud is suspected, a customer’s matter may be referred to the Fraud Investigations Branch for further investigative action and then potentially to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions for further action. |

Table 1 Information flow in the NEIDM process, updated to match the current information process (Original source: Non-Employment Income Data Matching Process PIA, page 6-7).

Part 3: Findings

Our approach

3.1 The key findings of the assessment are set out below under the following headings:

- Implementing practices, procedures and systems to ensure APP compliance

- Collection of solicited personal information

- Collection notices

- Data analytics – secondary use of customer data

3.2 For each issue, we have outlined a summary of the OAIC’s observations, the privacy risks arising from these observations, followed by suggestions or recommendations to address those risks.

3.3 As part of this assessment the OAIC has considered:

- the APP Guidelines, which outline the mandatory requirements of the APPs, how the OAIC will interpret the APPs and matters the OAIC may take into account when exercising functions and powers under the Privacy Act

- the Guidelines on Data Matching in Australian Government Administration (the Data Matching Guidelines), which aim to assist Australian Government agencies to use data matching as an administrative tool in a way that complies with the APPs and the Privacy Act, and is consistent with good privacy practice.[6]

3.4 In accordance with the NEIDM program protocol, DHS seeks to comply with these guidelines for the purpose of its data matching activities.[7]

Implementing practices, procedures and systems to ensure APP compliance

3.5 APP 1.2 requires an entity to take reasonable steps to implement practices, procedures and systems that will:

- ensure that the entity complies with the APPs; and

- enable the entity to deal with privacy related inquiries or complaints from individuals.

3.6 DHS will also need to consider how it will comply with the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code (the Code) which was registered on 27 October 2017 for commencement on 1 July 2018. The Code sets out specific requirements and key practical steps regarding privacy governance and personal information management, that agencies must take as part of complying with APP 1.2. The OAIC notes that while the Code was not in scope at the time of the assessment, DHS will be required to comply with the Code as of 1 July 2018.

Internal practices, procedures and systems

Observations

DHS privacy framework

3.7 DHS has articulated the structure of its internal privacy staff and responsibilities within its privacy framework document. This framework is a one-page matrix and outlines the management of privacy responsibilities across DHS with references to key positions and business units.

3.8 The Programme Advice and Privacy Branch (privacy team) within DHS provides privacy advice and guidance to the business units, as well as conducting various other privacy responsibilities outlined in the DHS privacy framework. Business units request and are responsible for implementing the advice the privacy team provides. Business units actively monitor changes to a project that involves the handling of personal information and consult the privacy team to ensure continued compliance with the APPs. DHS’s privacy framework is discussed further in the ‘Governance, culture and training’ section.

3.9 The OAIC notes that the Code will require agencies (including DHS) to have privacy governance mechanisms in place, including appointing:

- a Privacy Officer or Privacy Officers, and ensure that particular privacy functions are undertaken

- a senior official as a Privacy Champion to provide privacy leadership and promote the values of personal information.

Privacy guidance for DHS staff

3.10 DHS’s internal operational privacy policy[8] outlines the importance of privacy and the responsibilities of all its staff to comply with the Privacy Act. The operational privacy policy extends to non-ongoing employees, contractors and consultants.

3.11 Staff are presented with the operational privacy policy when they begin their employment with DHS. Responsibilities outlined in this document include:

- only using personal information in the performance of their duties. Staff are required to sign a declaration holding them accountable for their handling of customers’ personal information

- conducting privacy threshold assessments (PTAs) and privacy impact assessments (PIAs) when starting new projects or changes to existing programs. The ‘Privacy impact assessments’ section discusses PIAs further

- the reporting of all complaints about suspected or actual privacy breaches to the DHS privacy inbox.

3.12 The OAIC was informed that the team responsible for implementing the NEIDM program followed the operational privacy policy in seeking legal advice regarding DHS’s legislated power to conduct the NEIDM program. DHS also engaged a third party to conduct a PIA to identify privacy risks and make recommendations to mitigate those risks for the NEIDM program.

3.13 The DHS intranet is also a source of privacy information for staff. This information is presented as a series of ‘frequently asked questions’ (FAQs) on general privacy questions such as sending personal information to an incorrect email address or what to do when unrequested personal information is received. The responses to these questions outline DHS’s expectations on how employees should conduct themselves when handling personal information.

Privacy incident management

3.14 DHS advised that staff use a template to report ‘privacy incidents’ to the privacy team. This template requires staff to provide:

- details about the incident

- the types of information involved and individuals affected

- any escalation or remedial action taken.

3.15 The template does not contain information about what constitutes a ‘privacy incident’, though this topic appears to be covered by FAQ 14 on the DHS intranet. Staff must then email the completed template to the DHS Privacy Team via a dedicated privacy inbox, as mandated by the DHS operational privacy policy, for investigation of the incident.

3.16 None of the materials given to the OAIC provided guidance to staff about when or how to escalate a privacy incident. Staff interviewed during fieldwork indicated that DHS is reviewing its privacy training materials to include privacy incident response training. This is discussed further in the ‘Governance, culture and training’ section of this report.

3.17 DHS’s privacy incident processes are also supported by its privacy framework. As part of its functions, the Privacy team is responsible for investigating reported privacy breaches and reporting on privacy matters. The Privacy team provides quarterly reports on privacy risks to the Executive Committee, General Managers and annually to the Secretary. This will be discussed further in the ‘Risk management’ section of this report.

3.18 DHS also has a document called ‘Guidelines for managing privacy incidents’, which sets out the steps to take following a ‘serious’ privacy incident and a ‘routine’ privacy incident. This document identifies some relevant position titles of whom are involved at different points of the incident response process, including who should be notified about certain incidents and what action should be taken. Whilst it identifies position titles and often nominates that a person in a particular role is to determine a course of action, the documents does not set out the information or criteria that this person can use to make their decision.

3.19 In addition, none of the documents discussed above mention the obligations of the Notifiable Data Breach (NDB) scheme, which commenced less than three months after this assessment fieldwork.

3.20 DHS advised that privacy incidents are recorded but did not provide any such evidence or register to the OAIC.

Managing customer complaints

3.21 DHS has an APP 1 privacy policy[9] that provides customers with information on how DHS handles customers’ personal information. DHS also has a number of linked web pages[10] that further expand on individuals’ rights to privacy, how privacy affects customers and when DHS shares customers’ personal information. Customers also have the right to ask DHS to review a decision about a Centrelink payment or service, Medicare debt or child support.[11]

3.22 There are a number of ways a customer can make a privacy related enquiry or complaint to DHS. Customers are able to contact DHS via phone, email, web or fax. DHS’s privacy policy advises customers on how to make a privacy complaint and explains how DHS will deal with such a complaint. DHS also provides further information on complaints and feedback on its website. If a customer wishes to make a complaint to DHS, they can call a dedicated phone number or complete a web form. Once a complaint is received, DHS will aim to resolve the issue within 10 working days. If this is not possible, DHS will explain why and let the customer know if there are other options available to resolve their complaint.

Analysis

Privacy management plan

3.23 Good privacy management requires the development and implementation of robust and effective internal policies, practices, procedures and systems that ensure the handling of personal information in line with DHS’s privacy obligations. This includes the development and implementation of a PMP. A PMP assists in embedding a culture of privacy that enables privacy compliance. It identifies specific, measurable privacy goals and targets and sets out how an entity will meet its compliance obligations under APP 1.2.

3.24 The OAIC notes that while the DHS’s privacy framework sets out roles and responsibilities of privacy management within DHS. It should go further to meet its compliance obligations, by identifying specific, measurable goals and targets for privacy management.

3.25 As mentioned earlier, the Code sets out specific requirements and key practical steps that agencies must take as part of complying with APP 1.2 (agencies will still need to take other steps under APP 1.2 to ensure compliance with all the APPs). One of the requirements for agencies under the Code is to have in place a PMP.

3.26 As part of meeting its obligations under APP 1.2 and the Code, DHS should develop and implement a PMP, reviewed annually, that sets out specific goals and objectives for its privacy management with consideration of the specific issues that apply to its operations.[12]

3.27 Whilst DHS has a number of documents that cover some of the OAIC’s expectations regarding a data breach response plan, the information is dispersed over several documents. This arrangement may be difficult for staff to understand how to identify a privacy incident, and to report and escalate an incident in a timely manner. If staff are not aware of all the various documents needed to assist in reporting or escalating an incident, then there is a medium risk that the incident will not be managed appropriately.

3.28 The OAIC recommends that DHS review its current policies and procedures about responding to privacy incidents with the view of creating a single streamlined data breach response plan document, which sets out DHS’s strategy for containing, assessing and managing breaches from start to finish. Having a clearly documented process will enable staff to follow clear identification and mitigation procedures and escalation channels in the event of a breach involving the NEIDM program. In doing so, DHS should consider the OAIC’s guidance on data breach response plans as set out in Part 2 of the OAIC’s Data breach preparation and response - A guide to managing data breaches in accordance with the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

3.29 The documents described above could, if collated and amended, be used as the basis of a data breach response plan. For example, information about what constitutes a privacy incident could be included in the reporting template, rather than separately in the FAQ section of the intranet.

3.30 For the Guidelines for managing privacy incidents, it is not clear whether this document is intended for use by all staff, or whether it is for the benefit of a specific team, such as the Privacy Team, once an incident is reported.

3.31 As of 22 February 2018, the NDB scheme, contained in Part IIIC of the Privacy Act, imposes requirements for entities (including DHS) in responding to data breaches. DHS now has data breach notification obligations when a data breach is likely to result in serious harm to any individuals whose personal information is involved in the breach.

3.32 Any data breach response documentation should specifically set out the criteria for determining when and how to notify affected individuals and external stakeholders, including, any legislative or contractual requirements such as those under the NDB scheme.

Recommendation 1

The OAIC recommends that DHS develop and implement the following policy documents:

- a privacy management plan articulating DHS’s overall goals and objectives for privacy. This will also become a mandatory requirement under the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code, which commenced on 1 July 2018.

- a clear and cohesive data breach response plan. Having a single streamlined document will enable staff to follow clear identification and mitigation procedures and escalation channels in the event of a breach involving the NEIDM program.

Program protocol

Observations

3.33 The NEIDM program protocol provides customers with an overview of the data matching program and how customers’ personal information is used in the program. DHS stated that it followed guidance set out in Appendix A of the OAIC’s Data Matching Guidelines when developing the protocol. DHS published the NEIDM program protocol in August 2016. DHS advised that the protocol must be reviewed every three years.

3.34 DHS advised that the ATO, while provided with a copy of the program protocol by DHS, was not actively involved in its development. When asked if the ATO complies with the program protocol, DHS could not comment at the time of the assessment.

3.35 DHS also advised that it is currently developing its strategy for appropriate handling of partner and nominee information under the NEIDM program. This issue is not discussed in the current version of the protocol.

3.36 The OAIC noted that the current program protocol, available online, references an attachment B (the public notice) but the public notice is no longer included in the protocol.

Analysis

3.37 Under the OAIC’s Data Matching Guidelines, Guideline 3 outlines that before commencing a data matching program, the primary user agency should:

- prepare a program protocol in accordance with Appendix A (of the Data Matching Guidelines)

- provide a copy of the program protocol to the OAIC

- make the program protocol publicly available.

3.38 Guideline 3 also indicates that each entity involved in the data matching program should ensure its participation complies with the program protocol.

3.39 Appendix A of the Data Matching Guidelines indicates that the program protocol should contain the following information:

- a description of the data matching program

- reasons for deciding to conduct the data matching program.

3.40 Guideline 4 of the Data Matching Guidelines suggests the matching agency detail the technical standards for governing the conduct of the data matching program in a technical standard report as set out in Appendix B. The technical standard report should clearly document, among other things, the following information about the data matching techniques to be used in the data matching program:

- description of data used during the matching process

- matching techniques used in the data matching program, for example matching algorithm used, rules for recognising matches, techniques adopted to overcome identifiable problems with the quality of data and to standardise data items that have been compared but have different meaning (for example, ‘annual income’ and ‘financial year income’)

- risks posed by the data matching program including, but not limited to, risks to the privacy of individuals, reputational risks, and risks relating to incorrect matches

- precautions proposed to be taken at all stages of a data matching program to ensure that personal information used in and arising from a data matching program is protected.[13]

3.41 While the NEIDM program protocol provides customers with an overview of the purpose, scope and objective of NEIDM, it does not fully meet the requirements outlined in the Data Matching Guidelines. Specifically, details regarding the use of business rules and filtering should be added or expanded in existing text of the program protocol to provide a clearer explanation of the data processes once the matched data is collected from the ATO.

3.42 Under APP 1, entities are required to manage personal information in an open and transparent manner. This requirement is also emphasised in the Data Matching Guidelines to ensure that entities provide a level of transparency and accountability for their data matching programs. By having a clearly written and informative program protocol, entities will be able to inform the public about the existence and nature of the data matching program[14] and demonstrate their transparency and accountability obligations.

3.43 A program protocol is also important for guiding DHS staff on how personal information is handled under the NEIDM program. Under APP 1.2, entities are required to take reasonable steps to implement practices, procedures and systems that ensure compliance with the APPs. Entities are at risk of losing corporate knowledge and its staff not following appropriate procedures if they fail to accurately document their internal processes in detail. By clearly articulating their data matching processes in the technical standards report, DHS can ensure that they have documented this corporate knowledge to prevent losing it in the future and maintain continuity for staff within a program.

3.44 The OAIC acknowledges that adding additional information into the protocol regarding how DHS processes the matched data from the ATO will need to be considered carefully as there may be issues of confidentiality or sensitivity. With these considerations in mind, the OAIC recommends that DHS, as part of its scheduled review of the program protocol, identify what additional information should be included, in accordance with the APPs and the Data Matching Guidelines.

3.45 As noted above, while the program protocol is an external document, published to provide the community with information on DHS’s data matching activities under the NEIDM program, it is also a vital source of corporate knowledge to ensure departmental consistency. Therefore, the OAIC considers that there may be value in creating an internal version of this protocol, which would expand on the technical aspects of the program. The internal protocol will also assist with DHS’s own internal risk management and audit processes as well as demonstrating compliance to external regulators.

3.46 The OAIC also suggests that DHS removes any reference to Attachment B (the public notice) from the program protocol, as the public notice is no longer included in the protocol published on the DHS website.

3.47 As indicated earlier, DHS could not comment, at the time of the assessment, if the ATO complies with the program protocol. The OAIC suggests that DHS increase their oversight over how the ATO conducts data matching. This issue is discussed later in the report.

Recommendation 2

The OAIC recommends that DHS review the program protocol to identify what additional information should be included, in accordance with the APPs and the Data Matching Guidelines. Specifically, DHS should expand on the use of business rules and filtering within the program protocol. Should these details be considered sensitive in nature, the OAIC suggests that DHS consider also creating an internal, more detailed version of the protocol for auditing, monitoring and quality control purposes.

Privacy impact assessments

Observations

3.48 DHS’s operational privacy policy requires its staff to undertake a PTA for all new projects, and for any other activities that involve changes to the way DHS manages (i.e. collects, discloses, stores or uses) any personal information.

3.49 If the PTA identifies that the project or activity involves a significant change to DHS’s management of the personal information involved or has a significant impact on the privacy of individuals, a PIA is required, unless otherwise authorised by the Secretary or a Deputy Secretary of the DHS.

3.50 The privacy team has implemented a process for DHS staff to undertake PTAs, with information and guidance on how to complete a PTA available on DHS’s intranet. The privacy team also provides support or assistance where required.

3.51 In regards to the NEIDM project, DHS engaged Clayton Utz to conduct an independent PIA. The focus of that PIA was on the privacy risks of collecting, using and disclosing customers’ personal information in a manner that is different to the legislatively prescribed arrangements set out in the DMP Act. Clayton Utz provided DHS with seven recommendations.

3.52 DHS has accepted and taken steps to implement all the recommendations. The OAIC notes that some of these recommendations, such as recommendation 4 (regularly review the operation of the algorithms used to data match as part of the NEIDM process) are ongoing in nature and require monitoring to ensure they are carried out. DHS advised that currently, there is no ongoing monitoring of the implementation of these recommendations.

3.53 DHS also advised the OAIC that the scope of the NEIDM program has changed since the finalisation of the PIA. In particular, whilst the original PIA was based on the NEIDM program using automatic intervention, the program has remained primarily manual, with staff assisting customers to ensure information used in debt calculation is accurate. DHS advised that the PIA for the program has not been revised following this change to the program.

3.54 The OAIC notes that DHS does not have a formal process for following up on ongoing recommendations from PIAs but understands that the privacy team is currently implementing processes to do this.

Analysis

3.55 PIAs are key to identifying privacy risks and controls to mitigate the risks during the planning stages for a project and can also be useful in managing ongoing risks.

3.56 The OAIC notes that DHS has thorough PIA processes in place regarding changes to projects or on boarding new projects, yet there is still a gap regarding the follow up of PIA recommendations, including recommendations made under the NEIDM program’s PIA. This raises the medium risk that privacy risks identified in PIAs will not be addressed.

3.57 The OAIC recommends that DHS develop a process for monitoring the implementation of PIA recommendations. This could involve the process currently being developed by the DHS privacy team.

3.58 For the NEIDM PIA, the OAIC recommends that DHS review and monitor the impact and relevance of its implementation of this PIA’s recommendations against the current NEIDM operating processes. In addition, by following up with ongoing recommendations made in the NEIDM PIA, the Data Strategy and Analytics business unit, which is part of the Compliance Risk Branch and is responsible for the NEIDM program, will have an increased awareness of potential privacy risks associated with its data matching activities.

3.59 For further information about the PIA process, the OAIC has published the Guide to undertaking privacy impact assessments, which may be of assistance in considering future PIAs.

3.60 From 1 July 2018, the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code will require DHS to keep a register of all PIAs conducted and publish this register, or a version of the register, on its website. This register may assist DHS in monitoring the implementation of its PIAs.

Recommendation 3

The OAIC recommends that DHS develops a process for monitoring the implementation of PIA recommendations, in particular the recommendations from the NEIDM PIA to ensure their relevance to the current NEIDM operating processes. This could involve the process currently being developed by the DHS privacy team.

Governance, culture and training

Observations

3.61 DHS appears to have a good privacy culture. Based on the OAIC’s review of DHS documents and interviews with DHS staff, there is a general awareness of privacy and security issues and a good general understanding of the importance of appropriate information handling practices.

3.62 DHS has a privacy framework that outlines its oversight and responsibility for privacy issues. The Chief Counsel, Legal Services Division has responsibility and oversight of the centralised support function for privacy within DHS. Centralised support functions are carried out by the privacy team. The framework also outlines the responsibilities of business areas and the information management branch. As mentioned, DHS staff must actively seek advice from the privacy team to ensure privacy is included as a consideration for new and evolving projects.

3.63 As outlined in the DHS operational privacy policy, it is the responsibility of business area officials to ensure that the management of personal information in their business areas correctly reflects the DHS privacy policy. The operational privacy policy requires business area officials to conduct twice-yearly audit checks ensuring that the privacy policy reflects any changes to process or practice. Based on information provided by DHS, it is unclear whether relevant data matching business areas are conducting these audit checks.

3.64 All staff at DHS are also required to undertake mandatory privacy and fraud awareness training upon commencement of employment. Each year all DHS staff are also required to complete refresher training on privacy and fraud. The OAIC understands that at the time of this assessment, this training material was under review to take into consideration upcoming changes to privacy laws.

Visibility over the ATO data matching process

3.65 As mentioned earlier in this report, the ATO conducts the data matching for NEIDM but the activities of the ATO were out of scope for the purposes for this assessment. Therefore, this assessment was limited to examining what governance or oversight that DHS has in place over ATO functions for ensuring compliance with the APPs.

3.66 DHS understands that the ATO uses proprietary software to conduct this data matching.

3.67 DHS is aware that the ATO uses confidence ratings to indicate the estimated level of accuracy for matched data. These confidence ratings are based on the number of identifiers such as name, address and birthday that the ATO is able to match to the DHS file. DHS receives files which fall within the top three confidence ratings from the ATO.[15] DHS was unable to provide the OAIC with further information regarding the confidence ratings used on the data by the ATO.

3.68 DHS advised that a number of communication channels exist between the ATO and DHS, allowing either entity to raise issues, trends or concerns including regular meetings and email correspondence. The two agencies have a number of high-level arrangements in place, including a general head agreement to manage their relationship, as well as a specific data exchange service schedule and a related arrangement to manage the exchange of data between the two agencies, which include references to the data exchanged for the NEIDM program. These written agreements are complemented by a governance committee and a data management forum.

Analysis

3.69 The DHS privacy team relies on business units to engage with them for advice and guidance when undertaking any action that may have a privacy implication. For this model to operate effectively, DHS staff and contractors need to be aware of potential privacy risks that may arise in the business as usual functions, as well as privacy risks that might arise when beginning a new project. DHS does have governance, training and PIA mechanisms (discussed in the ‘Privacy impact assessment’ section above) in place to ensure that staff work effectively with the privacy team to identify privacy issues.

3.70 Regular evaluation of DHS’s governance mechanisms will assist in the appropriate management of privacy risks. This correlates to the need for a documented PMP (discussed earlier), which would include ongoing evaluation as one of its privacy goals. DHS should then measure its performance against the PMP.

3.71 APP 1.2 requires entities to take steps as are reasonable to implement practices, procedures and systems relating to the entity's functions or activities that will ensure that the entity complies with the APPs.

3.72 Following fieldwork, the OAIC was advised that the Customer Compliance Division within DHS conducts ongoing reviews of its practices relating to the PAYG and NEIDM programs, driven by internal continuous improvement approaches, and linked with reviews by the Commonwealth Ombudsman and other departmental stakeholders.

3.73 Based on the information provided by DHS, it is unclear whether relevant data matching business areas within DHS are conducting twice-yearly audit checks to ensure the public facing APP 1 privacy policy correctly reflects the management of personal information in their business area.

3.74 By not ensuring that business areas comply with this requirement of the operational privacy policy, there is a medium risk that the public-facing APP 1 privacy policy does not accurately reflect the way that personal information is being collected, held, used and disclosed by DHS. The OAIC therefore recommends that DHS ensures the requirements of its operational privacy policy, including requirements for business areas to conduct twice-yearly audit checks of information in the public-facing APP 1 privacy policy, are followed.

3.75 Noting that the activities of the ATO were out of scope for this assessment, the OAIC suggests that DHS consider the visibility it has over how the ATO conducts the data matching process as part of the NEIDM program. This may include reviewing whether the ATO’s APP 1 privacy policy and APP 5 collection notices indicate that data matching will be conducted on income data.

3.76 The written agreements between DHS and the ATO, along with the forums, provide a level of assurance that these agencies are making adequate and appropriate arrangements to meet their privacy obligations and provide greater accountability, oversight and guidance in handling ongoing issues and disputes relating to data matching.

Recommendation 4

The OAIC recommends that DHS ensures the requirements of its operational privacy policy, including requirements for business areas to conduct twice-yearly audit checks of information in the public-facing APP 1 privacy policy, are followed.

Risk management

Observations

3.77 DHS has implemented a number of processes within its Customer Compliance Division (CCD) to assist with the management and mitigation of privacy risks in this division. While these processes are not specific to NEIDM, they assist in mitigating risks identified within that data matching program.

3.78 The CCD Executive oversees the data matching programs that DHS undertakes. Staff can raise or escalate issues or recommendations to the Executive directly, or through a Programme Performance Committee (PPC). This structure enables DHS to monitor program risks.

3.79 Failure to protect customer privacy and personal information is identified as one of DHS’s strategic risks. A quarterly report on this risk is provided by the Programme Advice and Privacy Branch, specifically by those responsible for responding to and monitoring this risk. This team has the responsibility to inform DHS’s Executive Committee about privacy incidents in the quarterly report.

3.80 DHS is also developing risk registers as part of a broader risk management plan to keep track of treatments and controls, and currently has created a dashboard to review risks. DHS aims to use this register to view the level of risks and their treatments and controls.

Analysis

3.81 The OAIC suggests that DHS continue with the development of its risk management initiatives, including the development of proposed risk management plan, risk registers and a risk management dashboard. These activities should assist DHS with the identification of privacy risks across its operations, including the NEIDM program.

Collection of solicited personal information

3.82 APP 3 provides the circumstances in which an agency may collect solicited personal information, including sensitive information.

3.83 APP 3.1 provides that an agency may only collect personal information (other than sensitive information) that is reasonably necessary for, or directly related to, one or more of its functions or activities.

3.84 APP 3.3 imposes an additional requirement for collecting sensitive information. An agency must not collect sensitive information about an individual unless:

- the individual consents to the collection of the information and the information is reasonably necessary for, or directly related to, one or more of the agency’s functions or activities, or

- one of the situations in APP 3.4 applies (this includes, for example, where the collection is required or authorised by law, or where the collection is necessary to reduce or prevent a serious threat to the life or health of an individual).

3.85 Under APP 3.5, an agency must only collect personal information by lawful and fair means.

3.86 Under APP 3.6, an agency must collect personal information about an individual only from the individual unless the individual consents to the collection of the information from someone other than the individual, or the agency is required or authorised by or under an Australian law, or a court/tribunal order, to collect the information from someone other than the individual.

Sources of personal information

Observations

3.87 The types of personal and sensitive information DHS collects are outlined in its APP 1 privacy policy.[16] Individual customers provide this personal and sensitive information to DHS to support a claim for payments or services. This information may include, for example, contact details, employment records and income, or medical reports. They are collected from customers using online and/or hard copy forms relevant to the services or payments that customers are seeking.

3.88 The personal information collected using these forms is part of the DHS data set that is used in the NEIDM data matching program. An example of this is the information DHS collects using its Income and Assets form, which requires customers to declare their annual income and assets. The Income and Assets form contains a privacy notice that refers customers to the link for DHS’s privacy policy and further information relating to privacy concerns. For further information on how this information is collected please refer to Figure 1.

3.89 The PIA undertaken for NEIDM considered APP 3 as a relevant privacy principle for this program and did not raise any issues in regards to its implementation or practice.

Purpose of collection

Observations

3.90 DHS’s functions and activities are governed by the Social Security Act 1991 and the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999, which allow DHS to determine individuals’ eligibility for, and provide them with access to, social, health and other payments and services.

3.91 The NEIDM program protocol states that, ‘[t]he program is related to…DHS’s lawful function of limiting payments to those eligible under relevant legislation’.

3.92 The OAIC did not encounter any documents or other information to suggest that DHS collects information from customers beyond what is reasonably necessary for DHS’s functions and activities. When further information is requested from customers who are the subject of compliance action under the NEIDM program, such information appears to be directly related to determining whether a customer has received the correct payment amounts from DHS.

Collection of sensitive information

Observations

3.93 As noted above, part of DHS’s governing legislation requires that information is collected from customers to determine their eligibility for payment as such the collection would be required by law.

3.94 In circumstances where that information is sensitive information, such as health information, DHS collects this information to determine eligibility for certain payments such as disability payments.

Lawful and fair means

Observations

3.95 The APP Guidelines state that a ‘fair means’ of collection is one that ‘does not involve intimidation or deception, and is not unreasonably intrusive’. Examples of unfair means of collection include, for example, collection from an individual who is traumatised or in shock, collection from a file accidentally dumped on a street, or collection by deception.[17]

3.96 There was no indication that DHS’s collection of information used in the NEIDM program involves unlawful or unfair means.

Collection of personal information from individuals and the ATO

Observations

3.97 As part of the matching process, DHS uses data that is collected from the ATO. This collection meets the requirements of one of the exceptions in APP 3.6, being that an entity can collect personal information from a source other than the individual where such collection is authorised by or under an Australian law.

3.98 As noted in the program protocol, the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 provides that DHS may require the provision of information of relevance to the assessment of claims for DHS’s payments, including whether a payment is or was payable to the person who received it or whether the rate is or was correct.

Collection by creation

Observations

3.99 Collection by creation is the creation of new personal information through data matching, data mining and data analytics.[18] An example of creating information through collection is when inferences are drawn about an individuals’ health (e.g. information about disability payments) or sexual orientation (e.g. individuals who report the name of their partner revealing they are in a same sex relationship), thus creating sensitive information.

3.100 The NEIDM program includes the processing of non-earned income, which in some customer payments may include medical payout, allowing for the inference of personal health information, and this could constitute collection by creation.

3.101 While DHS uses a generally robust privacy assessment process, the PTA form and the PIA report do not consider how personal information could be created in the future in a ‘collection by creation’ situation either through data matching or data analytics.

3.102 The OAIC notes that the PIA and the initial legal advice for the NEIDM program did not consider issues related to creation of new personal information (including sensitive information) from either matched data collected from the ATO or from undertaking data analytics.

Analysis

3.103 The OAIC does not have any major concerns about DHS’s collection of solicited personal information in relation to its obligations under APP 3. Personal and sensitive information is collected as required by DHS’s governing legislation and appears to be collected by lawful and fair means. The PIA conducted on this program supports this reasoning.

3.104 However, the use of customer data within DHS has changed through the increase in data matching activities and potentially through data mining and analytics. It is important that DHS recognises the potential privacy risk of ‘collection by creation’ when it matches datasets or undertakes data analytics, which can allow for the inference of new personal or sensitive information. The risk itself is in not making the customers aware that by providing their personal information, DHS may be able to create new personal or sensitive information about the customer, especially if a customer did not wish to provide that personal or sensitive information.

3.105 The OAIC suggests that DHS considers whether data matching under the NEIDM program leads to the generation of new personal information. If so, DHS should review its privacy training for staff, APP 5 collection notices, PTA form (for future projects) and its APP 1 privacy policy to ensure they properly reflect this issue.

3.106 The OAIC notes that the PIA and the legal advice did not consider issues related to creation of new personal information (including sensitive information) from matched data collected from the ATO or from data analytics.

3.107 The OAIC suggests that DHS review the initial legal advice it received to ensure that it is compliant with APP 3, in particular whether it has properly considered any ‘collection by creation’ issues with the NEIDM program.

3.108 When undertaking data analytics activities, which may result in collection by creation, DHS should consult the OAIC’s Guide to Data Analytics and the Australian Privacy Principles. This Guide may assist in reducing privacy risks when processing customer data.

APP 5 collection notices

3.109 APP 5 requires an APP entity that collects personal information (including sensitive information) about an individual to take reasonable steps either to notify the individual of certain matters or to ensure the individual is aware of those matters. An APP entity must take these reasonable steps before, at, or as soon as practicable after it collects the personal information.

3.110 The matters that an individual must be notified about are listed in APP 5.2 and include:

- the APP entity’s identity and contact details

- the fact and circumstances of collection

- whether the collection is required or authorised by law

- the purposes of collection

- the consequences if personal information is not collected

- the entity’s usual disclosures of personal information of the kind collected by the entity

- information about the entity’s APP Privacy Policy

- whether the entity is likely to disclose personal information to overseas recipients, and if practicable, the countries where they are located.

Observations

3.111 Under the NEIDM program, DHS provides APP 5 collection notices on the back of its claim forms and when it writes to customers requiring further information to accurately assess their circumstances. DHS provided the OAIC with template letters to customers and their partners used for the NEIDM program.

3.112 If, following the NEIDM data matching process, a customer is identified as having an income discrepancy, DHS sends them an initial letter. The letter outlines the customer’s income information and the discrepancy that DHS has identified. The letter requests that the customer contact DHS to confirm the accuracy of the income information, or to provide further clarification regarding the income information outlined in the letter.

3.113 If a customer does not respond within 28 days, then DHS staff attempt to reach the customer by telephone. As part of DHS meeting its obligations under APP 5, DHS includes a collection notice in the initial letter. This collection notice states that DHS undertakes data matching activities, provides customers with a list of the agencies DHS works with when conducting data matching, and gives information about how customers can provide feedback or lodge a complaint. The initial letter includes a brief description of the department’s data matching activities, a short paragraph on DHS’s privacy obligations and a link to DHS’s privacy web page where customers can find further information.

Analysis

3.114 DHS provides notification in its forms and letters before the collection of its personal information in accordance with the requirements of APP 5.

3.115 Under the NEIDM program, DHS will, in most cases, require customers to provide the department with personal information to assist in determining the existence or size of a debt they may have incurred. In order to determine this amount, DHS processes this personal information, which can have consequences to the customer.

3.116 DHS notifies the public about NEIDM by publishing the program protocol on its website, in accordance with Guideline 5 of the Data Matching Guidelines. In particular, Guideline 5.3 states that a ‘public notice of the data match activity is considered a ‘reasonable’ step for an agency to take to satisfy APP 5 obligations’. In addition to the public notification, DHS staff attempt to reach customers by telephone if they do not respond to the initial letter within 28 days.

3.117 There is a low risk that a customer providing personal information to DHS in these circumstances may not be aware of why it is be being collected. The OAIC suggests that DHS includes a brief explanation of the NEIDM program and/or a link to the program protocol within the collection notice, to ensure that customers are provided with information to help them determine whether they should provide their personal information, and what will be done with that information.

Data analytics – secondary use of customer data

Observations

3.118 The OAIC notes that the NEIDM PIA and legal advice did not consider potential secondary uses of matched NEIDM personal information. As mentioned earlier, the customer provides information to DHS in order to receive various services and payments via hard copy application, over the phone or online. This information is placed in a customer file, and this file can potentially be used for a number of data analytics purposes across DHS.

Analysis

3.119 Similar to ‘collection by creation’, DHS needs to be aware of the potential privacy risks arising from the secondary use of personal data, such as undertaking new data analytic projects using current NEIDM data sets. Use of large data sets of personal information is becoming a common trend as entities find new ways to use data to provide analytical insights. While under the DHS privacy policy there is a ‘no use except for explicitly stated’ policy, NEIDM and other data matching program outputs have the potential to be used in data analytics to assist DHS in the improvement of services, identify fraud patterns, and track social services trends.

3.120 The OAIC suggests that DHS considers if the NEIDM program will lead to any secondary uses of matched NEIDM personal information that may not be reasonably expected by DHS customers, for example, application of data analytics to derive trends, insights and other information from matched NEIDM data. If this occurs, it is important that DHS continues to comply with the Privacy Act. This includes ensuring that customers are aware of any potential secondary uses of their data through its NEIDM related collection notices (discussed above) as well as DHS’s APP 1 privacy policy.

Part 4: Recommendations and responses

Recommendation 1

4.1 The OAIC recommends that DHS develop and implement the following policy documents:

- a privacy management plan articulating DHS’s overall goals and objectives for privacy. This will also become a mandatory requirement under the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code, which commenced 1 July 2018.

- a clear and cohesive data breach response plan. Having a single streamlined document will enable staff to follow clear identification and mitigation procedures and escalation channels in the event of a breach involving the NEIDM program.

DHS response

4.2 Agreed. The Department’s Legal Services Division has developed both a Privacy Management Plan and a Data Breach Response Plan in keeping with the requirements of the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code.

Recommendation 2

4.3 The OAIC recommends that DHS review the program protocol to identify what additional information should be included, in accordance with the APPs and the Data Matching Guidelines. Specifically, DHS should expand on the use of business rules and filtering within the program protocol. Should these details be considered sensitive in nature, the OAIC suggests that DHS consider also creating an internal, more detailed version of the protocol for auditing, monitoring and quality control purposes.

DHS response

4.4 Agreed. DHS undertakes regular reviews of the program protocol including the business rules to ensure the program delivers on the objectives of the program while remaining aligned to the APPs and the OAIC Guidelines on Data Matching in Australian Government Administration. The issues identified in this recommendation have been addressed.

Recommendation 3

4.5 The OAIC recommends that DHS develop a process for monitoring the implementation of PIA recommendations, in particular the recommendations from the NEIDM PIA to ensure their relevance to the current NEIDM operating processes. This could involve the process currently being developed by the DHS privacy team.

DHS response

4.6 Agreed. The Department’s Legal Services Division is currently developing monitoring processes for PIA recommendations and undertakes to apply this recommendation.

Recommendation 4

4.7 The OAIC recommends that DHS ensures the requirements of its operational privacy policy, including requirements for business areas to conduct twice-yearly audit checks of information in the public-facing APP 1 privacy policy, are followed.

DHS response

4.8 Agreed. The department requires all officials to comply with its operational privacy policy.

Part 5: Description of assessment

Objective and scope of the assessment

5.1 The assessment was conducted under s 33 C(1)(a) of the Privacy Act, which allows the OAIC to assess whether an entity maintains and handles the personal information it holds in accordance with the APPs.

5.2 The objective of this assessment was to determine whether DHS maintains personal information, under the NEIDM program, in accordance with its obligations under the APPs.

5.3 The scope of this assessment was limited to the consideration of DHS’s handling of personal information against the requirements of APP 1 (open and transparent management of personal information), APP 3 (collection of solicited personal information) and APP 5 (notification of collection of personal information). Specifically, the assessment examined whether DHS:

- is taking reasonable steps to implement practices, procedures and systems in accordance with APP 1.2

- is collecting solicited personal information in accordance with APP 3

- is taking reasonable steps to notify individuals of the collection of personal information (APP 5.1)

- has privacy notices that address the matters listed in APP 5.2 (specifically, that describe DHS’s data matching activities under the NEIDM program)

Privacy risks

5.4 Where the OAIC identified privacy risks and considered those risks to be high or medium risks, according to OAIC guidance (Appendix A refers), the OAIC made recommendations to DHS about how to address those risks. These recommendations are set out in Part 4 of this report.

5.5 OAIC assessments are conducted as a ‘point in time’ assessment; that is, our observations and opinion are only applicable to the time period in which the assessment was undertaken. However, during the assessment, DHS advised the OAIC that the NEIDM program may change in the future. With this in mind, the OAIC also considered where appropriate, possible future uses of data within the NEIDM program when making recommendations to help DHS pursue best privacy practices going forward.

5.6 For more information about privacy risk ratings, refer to the OAIC’s ‘Risk based assessments – privacy risk guidance’. Chapter 7 of the OAIC’s Guide to privacy regulatory action provides further detail on this approach.

Timing, location and assessment techniques

5.7 The OAIC conducted a risk-based assessment of DHS’s NEIDM program and focused on identifying privacy risks to the effective handling of personal information in its relation to the APPs.

5.8 The assessment involved the following:

- review of relevant policies and procedures provided by DHS

- fieldwork, which included interviewing key members of staff and reviewing further documentation, at the DHS office in Canberra on 24 October and 25 October 2017.

Reporting

5.9 The OAIC publishes final assessment reports in full, or in an abridged version, on its website. All or part of an assessment report may be withheld from publication due to statutory secrecy provisions, privacy, confidentiality, security or privilege. This report has been published in full.

Appendix A: Privacy risk guidance

| Privacy risk rating | Entity action required | Likely outcome if risk is not addressed |

|---|---|---|

|

High risk

Entity must, as a high priority, take steps to address mandatory requirements of privacy legislation | Immediate management attention is required This is an internal control or risk management issue that if not mitigated is likely to lead to the following effects |

|

Medium risk Entity should, as a medium priority, take steps to address Office expectations around requirements of privacy legislation | Timely management attention is expected This is an internal control or risk management issue that may lead to the following effects |

|

Low risk Entity could, as a lower priority than for high and medium risks, take steps to better address compliance with requirements of privacy legislation | Management attention is suggested This is an internal control or risk management issue, the solution to which may lead to improvement in the quality and/or efficiency of the entity or process being assessed. |

|

Footnotes

[1] Office of the Australian Information Commission Guidelines on Data Matching in Australian Government Administration, June 2014, Key terms section.

[2] Department of Human Services, Non-Employment Income Data-Matching (NEIDM) Program Protocol, August 2016, p.3.

[3] Department of Human Services, Non-Employment Income Data-Matching (NEIDM) Program Protocol, August 2016, p.4.

[4] For the full list of information fields sent to the ATO by DHS, please refer to the technical standards section of the DHS NEIDM program protocol, available via https://www.humanservices.gov.au/organisations/about-us/publications-and-resources/centrelink-program-data-matching-activities.

[5] For the full list of information fields sent from the ATO to DHS, please refer to the technical standards section of the DHS NEIDM program protocol, available via https://www.humanservices.gov.au/organisations/about-us/publications-and-resources/centrelink-program-data-matching-activities.

[6] Guideline 1 provides that the Guidelines apply to data matching programs that include the comparison of two or more data sets, and at least two of the data sets each contain information about more than 5000 individuals.

[7] Department of Human Services, Non-Employment Income Data-Matching (NEIDM) Program Protocol, August 2016, p.3.

[8] Version 2.0 - provided during fieldwork.

[9] Department of Human Services, Privacy policy.

[10] DHS privacy information: Your right to privacy; Access to information; Reviews and Appeals

[11] Please see the Department of Human Services, Review and appeal section for further information.

[12] The OAIC is developing a privacy management plan template and a privacy self-assessment tool, to assist agencies to assess the current state of their privacy practices and set privacy goals and targets. The OAIC website will be updated when this resource is available.

[13] For more information on the voluntary requirements outlined in the OAIC’s Guidelines on Data Matching in Australian Government Administration, please refer to Appendix B of the Guidelines.

[14] See Guideline 3.3 of the Guidelines.

[15] Commonwealth Ombudsman’s report into Centrelink's automated debt raising and recovery system.

[16] For a full list of personal information collected by DHS, see its collection of personal information document, which complements its APP 1 privacy policy.

[17] Chapter 3 of the OAIC’s APP Guidelines, paragraph 3.63.

[18] According to the OAIC’s Data matching guidelines, data analytics describes processes or activities, which are designed to obtain and evaluate data to extract useful information while data mining is the process of discovering meaningful patterns and trends by sifting through large amounts of data stored in repositories.