-

On this page

Publication date: 8 August 2023

Imprint page

The OAIC is an independent statutory agency established to promote and uphold privacy and information access rights. We have a range of regulatory responsibilities and powers under the Privacy Act 1988, Freedom of Information Act 1982 and Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010.

Our research helps to inform our approach to regulation, law reform, strategy and education. OAIC research is available at: oaic.gov.au/research

For enquiries about OAIC research, please contact corporate@oaic.gov.au

The OAIC acknowledges Traditional Custodians of Country across Australia and their continuing connection to land, waters and communities. We pay our respect to First Nations people, cultures and Elders past and present.

The OAIC would like to thank Lonergan Research who conducted this research on our behalf and co‑developed this report.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence, with the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, logos, any third-party material, any material protected by a trademark and any images and photographs.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (2023) Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey 2023, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, Australian Government.

Commissioner’s foreword

Three years since our last Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey (ACAPS), several significant events have pushed privacy into the community spotlight, including the COVID-19 pandemic, high-profile data breaches and the speed of tech innovation.

Three years since our last Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey (ACAPS), several significant events have pushed privacy into the community spotlight, including the COVID-19 pandemic, high-profile data breaches and the speed of tech innovation.

These events have intensified the focus on the role privacy plays in our sense of control and autonomy, human dignity, freedom and other key values.

As we release our latest ACAPS, we are at a pivotal moment for privacy in Australia, where we can seize the opportunity to ensure laws and practices uphold this fundamental human right into the future.

Our survey provides a valuable window into the sentiment of the community and a snapshot of how recent events have impacted them. For example, just under half of Australians surveyed told us they were affected by a data breach in the previous year, and three-quarters experienced harm as a result.

The advent of technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and facial recognition have introduced the potential for new privacy risks, some that deeply intersect with our human rights. While AI has the potential to provide major economic benefits, we know Australians are cautious about the use of AI to make decisions that might affect them, and there are low levels of comfort in the use of the technology.

Despite the heightened awareness and concern about privacy among the community, there is limited knowledge of what to do about it.

Nine in ten Australians have a clear understanding of why they should protect their personal information, up from 85% in 2020.

Some take action out of concern for their privacy, like checking emails, texts and calls are not scams before providing their information and using unique passwords and not sharing them.

But only 21% say their privacy knowledge is ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’, and 57% say they care about their data privacy, but do not know what to do about it.

Providing Australians with the right information and offering real privacy choices will empower them to protect their privacy.

Only 2 in 5 people feel most organisations they deal with are transparent about how they handle their information, and 58% say they do not understand how it is used.

Half of Australians surveyed believe that if they want to use a service, they have no choice but to accept what the service does with their data.

Yet 84% want more control and choice over the collection and use of their information.

This highlights the need to support individuals to take control of their privacy, for example, through privacy education and being clear about how their information is used, so they can make informed choices. However, it also emphasises the need for personal information handling practices to be inherently fair and reasonable.

Not only is good privacy practice the right thing to do and what the community expects, it is a precondition for the success of an innovative economy and gaining Australians’ trust and confidence.

The findings point to several areas where organisations can do more to build consumer trust. Trust is essential, as we know from our survey the level of trust in an industry sector impacts what information the community considers fair and reasonable to provide.

The most trusted sectors are also more likely to be relied on to do the right thing when it comes to specific practices, such as only collecting the information necessary to provide the service.

And consumers place a high value on privacy when choosing a product or service, with it ranking only after quality and price. They are even prepared to experience some inconvenience if their privacy is guaranteed.

We are on the cusp of the most significant changes to our privacy framework in over a decade, which presents an opportunity to ensure the protections the community expects are reflected in the law.

The survey points to ongoing opportunities to enhance Australia’s privacy framework, and there is strong support for government legislation that protects personal information.

We need to consider the laws and practices that will uphold our fundamental human right to privacy and meet community expectations, while enabling innovation and economic growth.

The OAIC will use the findings of ACAPS 2023 to inform our ongoing input into the review of the Privacy Act and to target our activities at areas of high concern among the community. We look forward to working closely with regulated entities to increase community trust and confidence in the protection of their personal information.

Angelene Falk

Australian Information Commissioner and Privacy Commissioner

Overview

ACAPS is a longstanding study commissioned by the OAIC to evaluate the awareness, understanding, behaviour and concerns about privacy among Australians. The research was first conducted in 1990 and took on its current form in 2001. It provides longitudinal information on Australians’ attitudes to key privacy issues, their experiences and perspectives around the use and protection of their personal information and the action they take to safeguard their privacy.

Since the last report in 2020, there have been some notable shifts in Australians’ awareness and attitudes towards privacy, driven by several events.

High-profile data breaches have drawn attention to the collection, retention and protection of personal information.

New applications and the increasing prevalence of technologies such as artificial intelligence and facial recognition have also presented new privacy considerations.

ACAPS 2023 has continued to evolve from earlier surveys. In particular, this survey explores biometrics and data breaches and harms that can result in more detail.

The main objectives of the 2023 survey are to:

- provide insights on Australians’ privacy attitudes and behaviours

- identify Australians’ awareness of and concerns about key and emerging privacy issues

- understand how Australians’ privacy awareness, attitudes and behaviours have changed over time

- collect data to assist the OAIC as the national privacy regulator across enforcement, compliance, policy, education and communications initiatives.

The OAIC commissioned Lonergan Research to undertake ACAPS 2023. The survey was conducted in March 2023 with a nationally representative sample of 1,916 unique respondents aged 18 and older.

Main findings

Watch our animated video or see our infographic for some of the key findings of ACAPS 2023.

Introduction to privacy

Three in five (62%) Australians see the protection of their personal information as a major concern in their life.

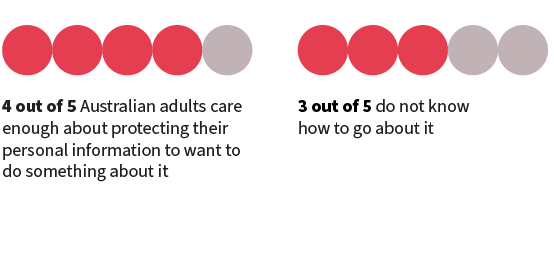

Eight in ten (82%) people care enough about protecting their personal information to do something about it, however 57% do not know what to do.

Only a third (32%) of Australians feel in control of their data privacy, and 84% want more control and choice over the collection and use of their personal information.

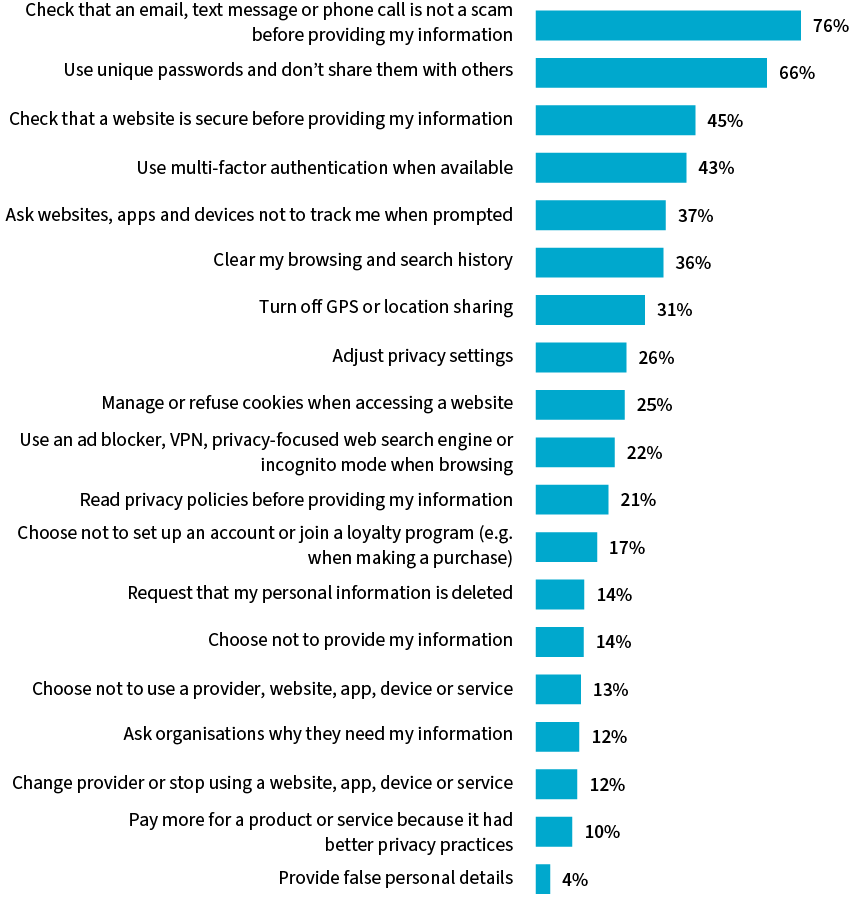

The 2 most common steps Australians are taking out of concern for their data privacy are checking an email, text message or phone call is not a scam before providing their information, and using unique passwords and not sharing them.

Three-quarters (74%) of Australians feel data breaches are one of the biggest privacy risks they face today. This has increased by 13 percentage points since 2020.

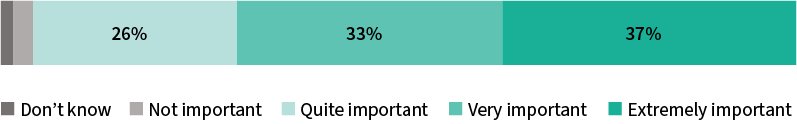

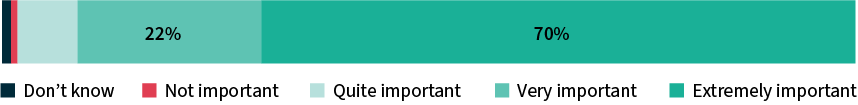

Most Australians place a high level of importance on their privacy when choosing a product or service, with 70% saying it is extremely or very important and another 26% stating it is quite important.

After quality and price, data privacy is the third most important factor when choosing a product or service.

Privacy legislation

While many Australians do not know exactly how they can protect their own personal information, the majority would like business and government agencies to do more in this area.

Seven in ten (69%) Australians said they are aware of the Australian privacy law that promotes and protects the privacy of individuals, and 89% want the government to provide more legislation in this area.

Almost all Australians think they should have additional rights under the Australian Privacy Act. These include the right to:

- ask a business to delete their personal information (93% believe they should have this right)

- object to certain data practices while still being able to access and use the service (90%)

- seek compensation in the courts for a breach of privacy (89%)

- know when their personal information is used in automated decision-making if it could affect them (89%)

- ask a government agency to delete their personal information (79%).

Australians are generally unaware some organisation types are exempt from the Privacy Act. The majority believe political parties and representatives (82%), businesses collecting work‑related information about employees (81%), media organisations in relation to their journalism activities (78%) and small businesses (77%) should be required to protect personal information in the same way as federal government agencies and larger businesses.

The role of organisations

Three in five (58%) Australians do not know what organisations do with their data. People often feel they have no choice but to hand over their personal information if they want to access a service (50% agree or strongly agree).

Australians trust health service providers and federal government agencies the most and social media companies and real estate agencies the least when it comes to the protection and use of their personal information.

Less than half of people trust organisations to only collect the information they need, use and share information as they state, store information securely, give individuals access to their personal information and delete information when no longer needed.

Most Australians (91%) are concerned about the prospect of their personal data being sent overseas.

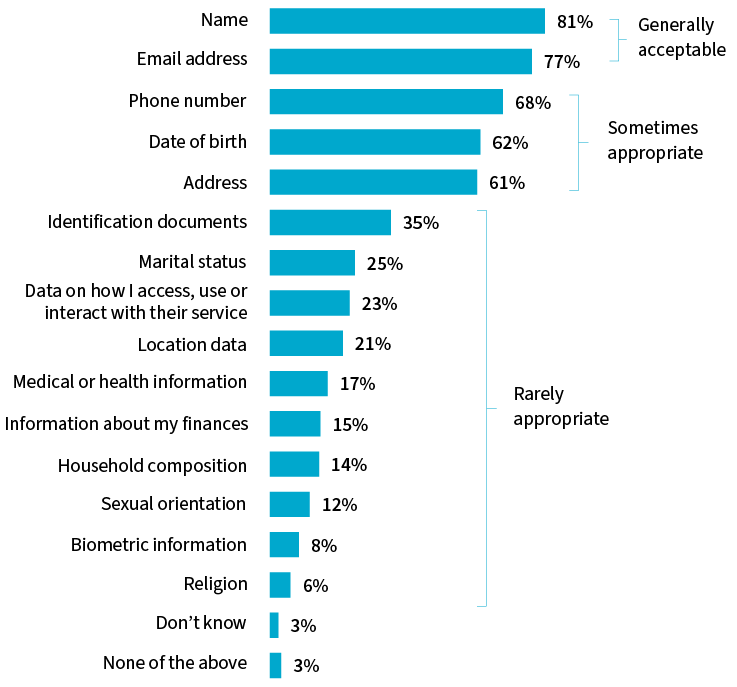

Over half (55%) of Australians consider having to share some personal information if they want to use a service fair enough. However, they generally only consider it fair and reasonable to provide their name (81%) and email address (77%) to organisations and, to a lesser extent, their phone number (68%), date of birth (62%) and physical address (61%).

There are certain practices Australians consider not fair and reasonable, including the online tracking, profiling and targeting of advertising to children (89% not fair and reasonable).

Privacy breaches and harm

Almost half (47%) of Australians said they had been informed by an organisation that their personal information was involved in a data breach in the 12 months prior to completing the survey in 2023.

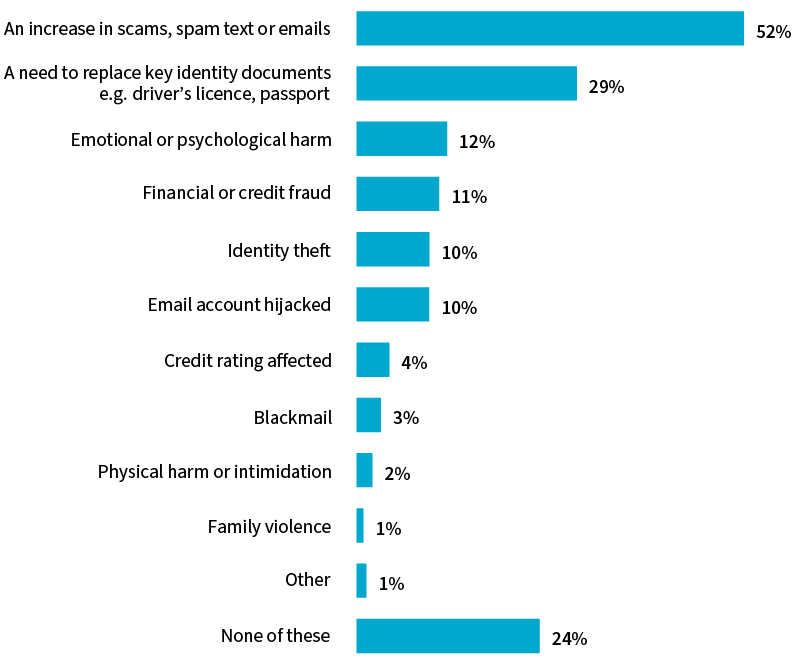

Three-quarters (76%) said they experienced harm as a direct result. Half (52%) saw an increase in scams and spam and almost a third (29%) said they had to replace key identity documents, such as a driver’s licence or passport. One in ten (12%) experienced emotional or psychological harm.

Almost half (47%) of people say they would stop using a service if their data was involved in a breach, but this drops to a third for people who have recently experienced a breach.

When it comes to dealing with the impacts of a breach, only 1 in 10 (12%) people said there was nothing an organisation could do to appease them. Most Australians are willing to remain with an organisation that has suffered a data breach, provided the organisation quickly takes action, such as putting steps in place to prevent customers from suffering harm.

A quarter (26%) of Australians believe the most important way an organisation can protect their personal information is by only collecting the information necessary to provide the product or service. Australians view the second most important action organisations can take is proactive steps to protect the information they hold (24%).

Digital technologies

Australians’ level of comfort with biometric information being collected and used depends largely on the type of organisation and the context.

People are generally more comfortable with one-to-one uses of their biometric information (such as to go through passport control at an airport) than they are with one-to-many uses and biometric analysis.

Australians are most comfortable with the collection and use of their biometric information in border security and law enforcement contexts, and they are more likely to trust the public sector to collect and use this kind of information than businesses.

When it comes to artificial intelligence (AI), 96% of Australians want some conditions in place before the technology is used to make a decision that might affect them, such as the right to have a human review the decision.

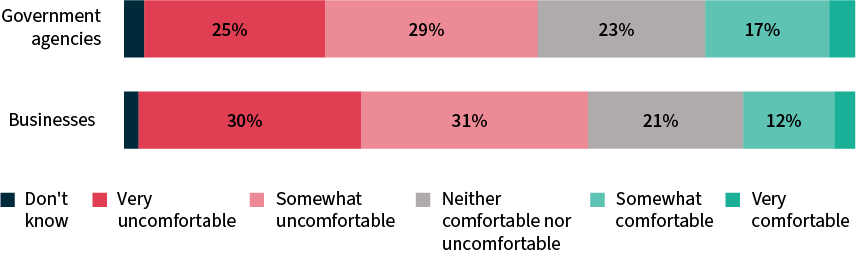

Australians are more comfortable with government agencies using AI to make decisions about them that use personal information than they are with businesses (20% comfortable for government agencies, cf. 15% for businesses).

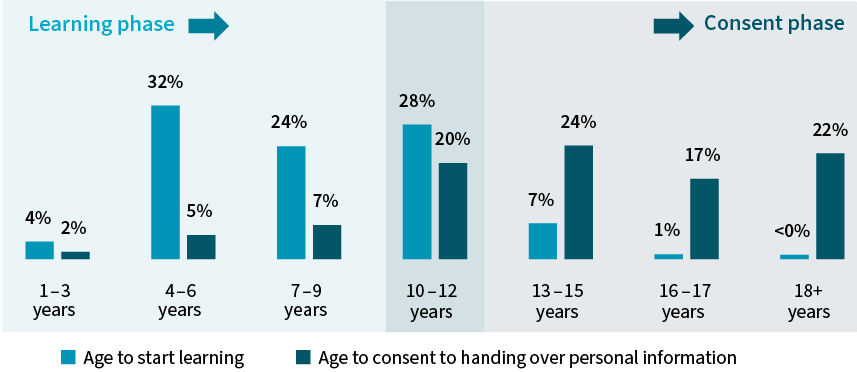

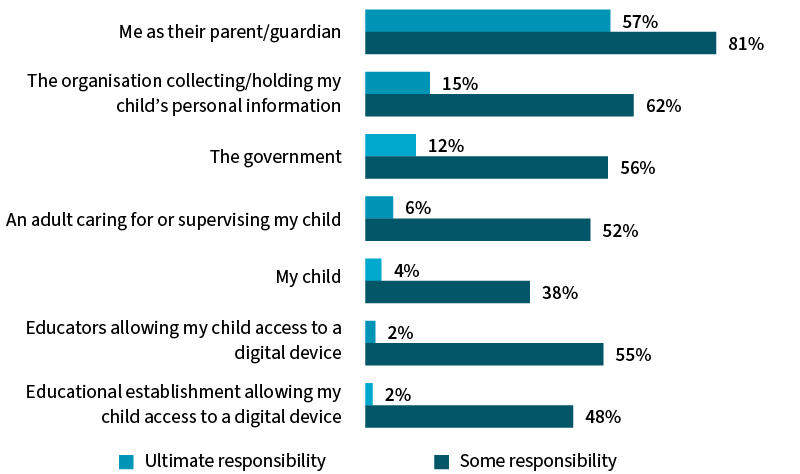

Children’s privacy

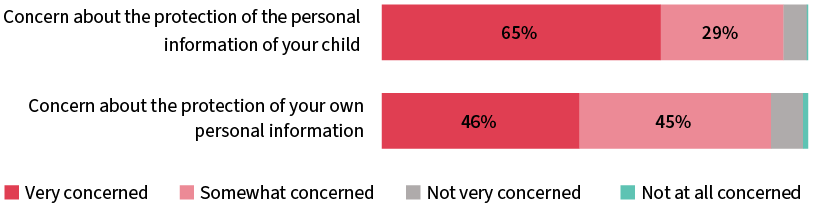

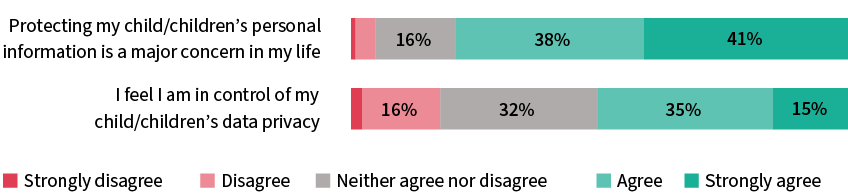

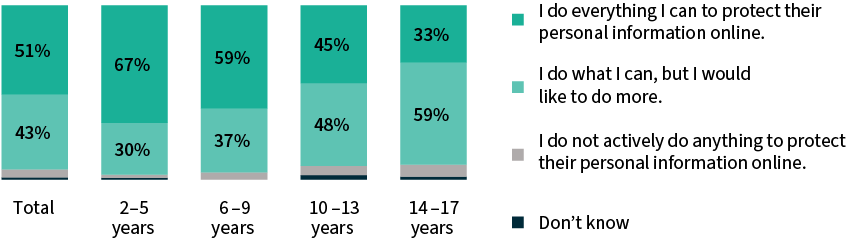

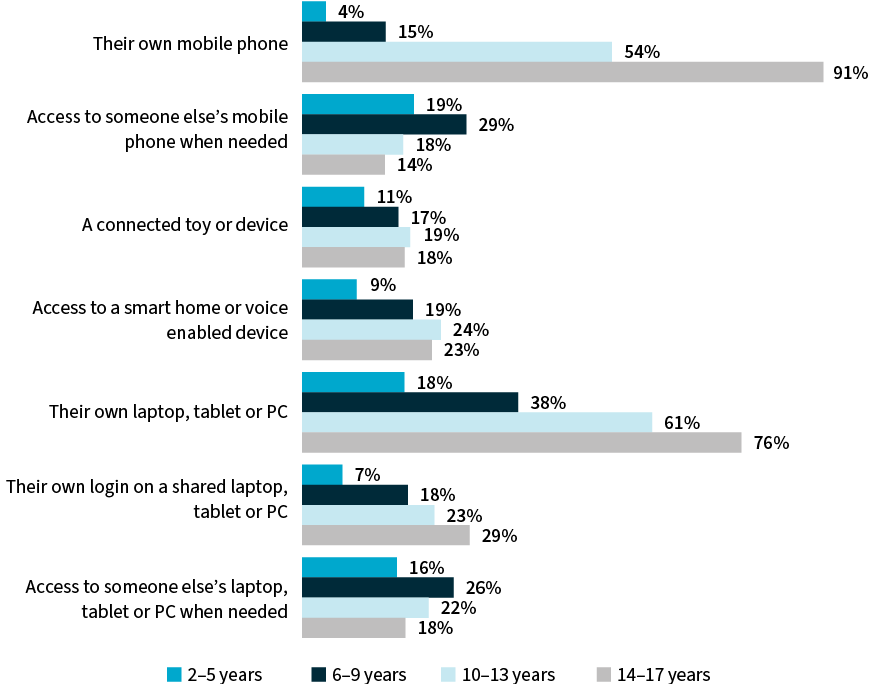

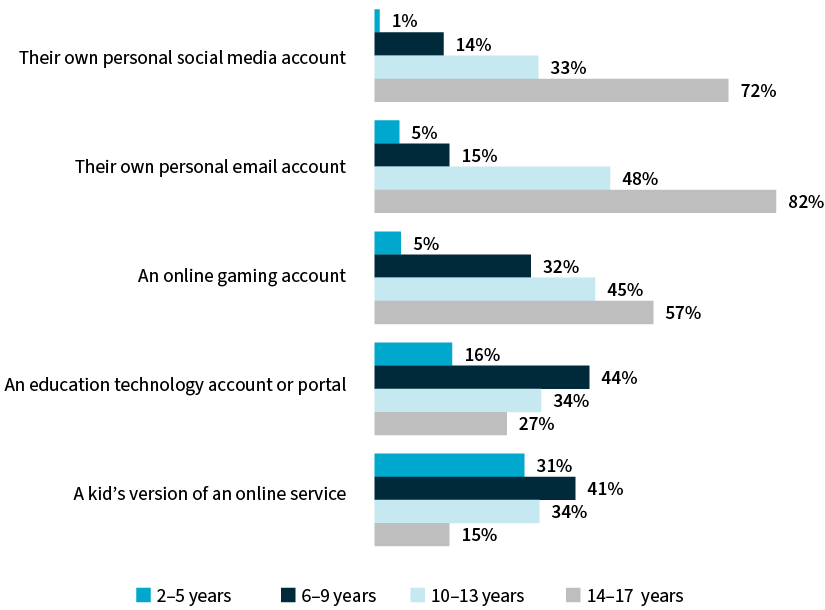

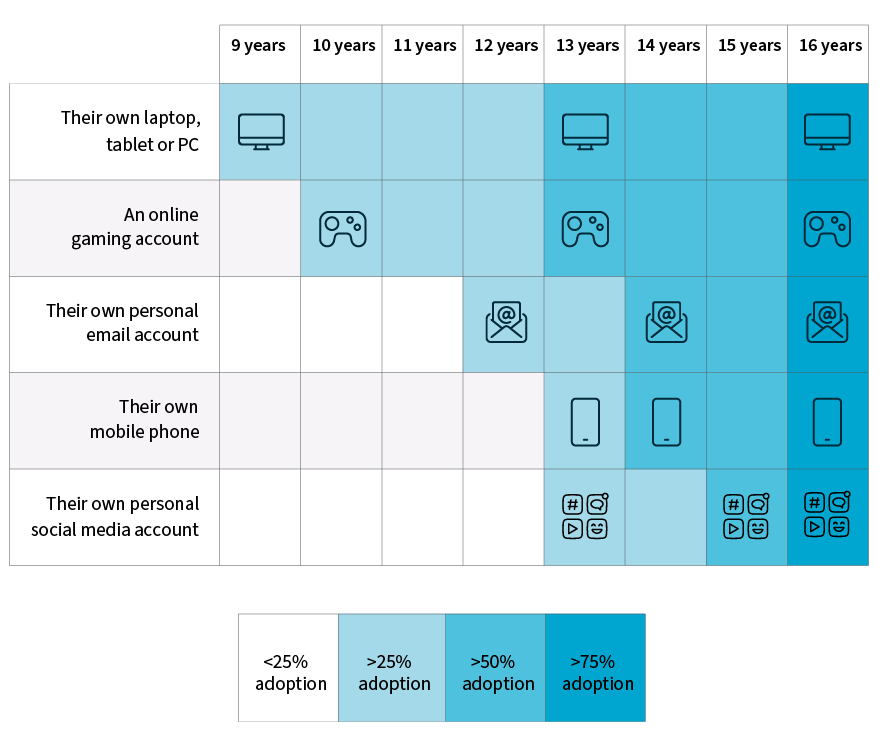

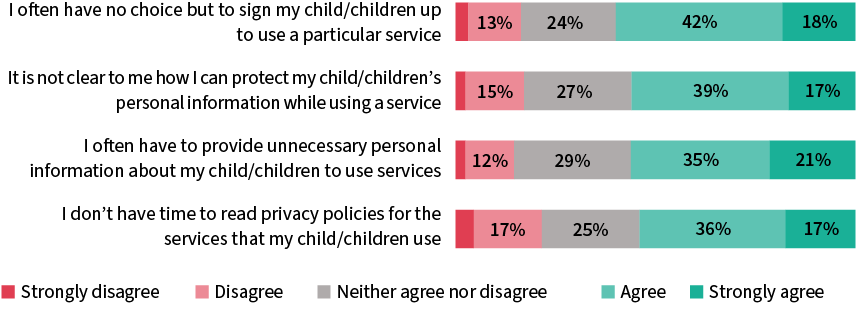

Protecting their child’s personal information is a major concern for 79% of parents. However, only half (50%) feel they are in control of their child’s data privacy.

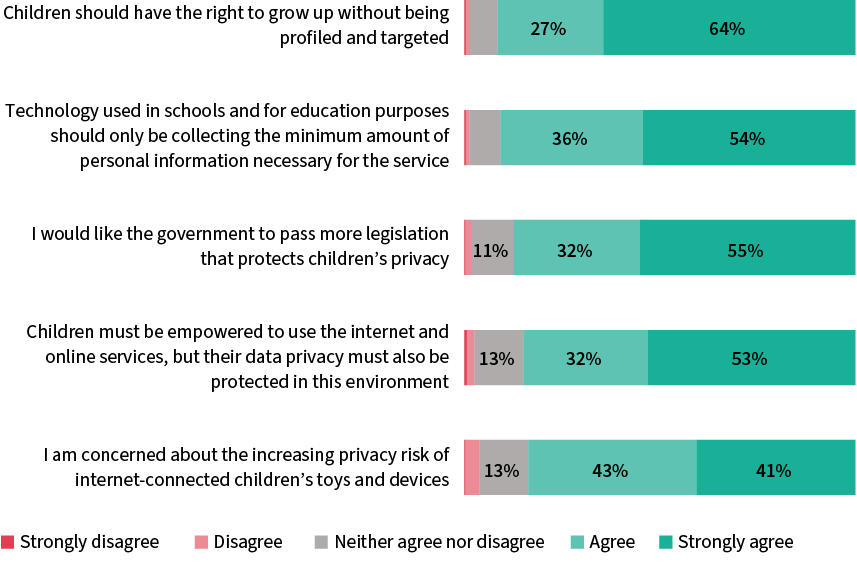

Eighty-five per cent of parents agree children must be empowered to use the internet and online services, but their data privacy must be protected.

For 91% of parents, the privacy of their child’s personal information is of high importance when deciding to provide their child with access to digital devices and services.

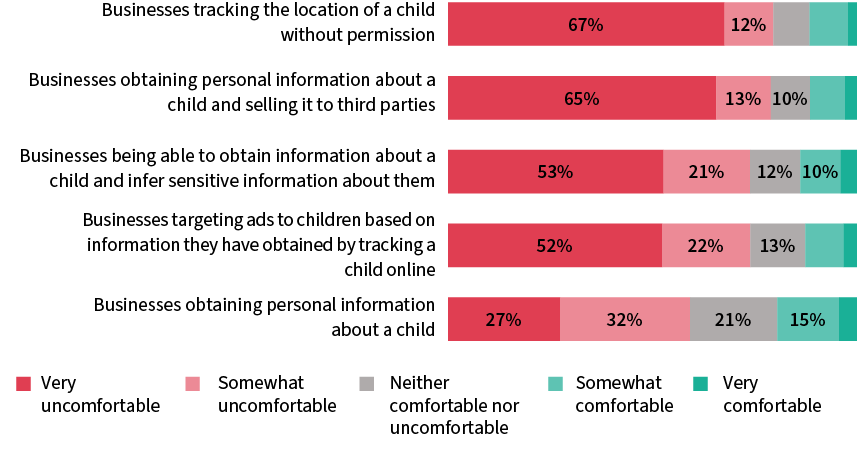

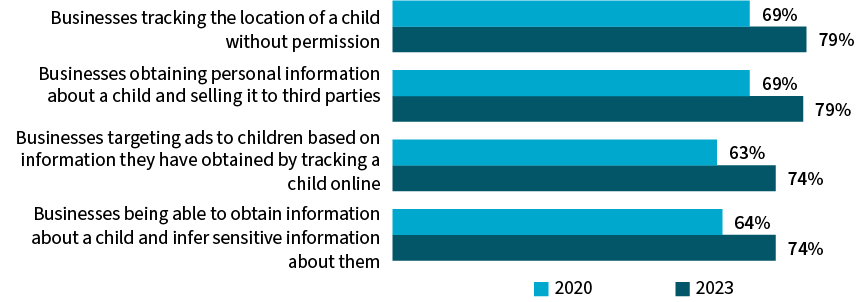

There is a great deal of discomfort around children’s privacy, especially with businesses tracking a child’s location without permission (79% uncomfortable) and businesses obtaining a child’s personal information and selling it to third parties (79% uncomfortable). Parents overwhelmingly (92%) believe children should have the right to grow up without being profiled or targeted.

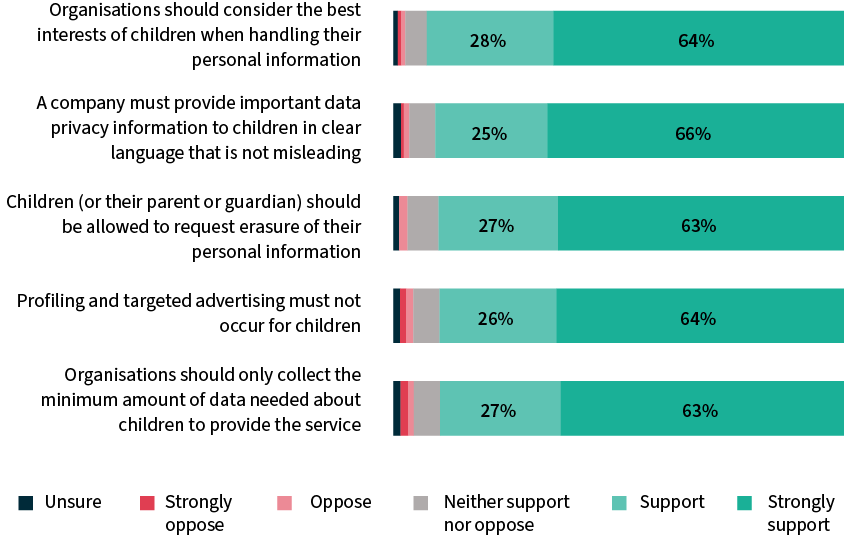

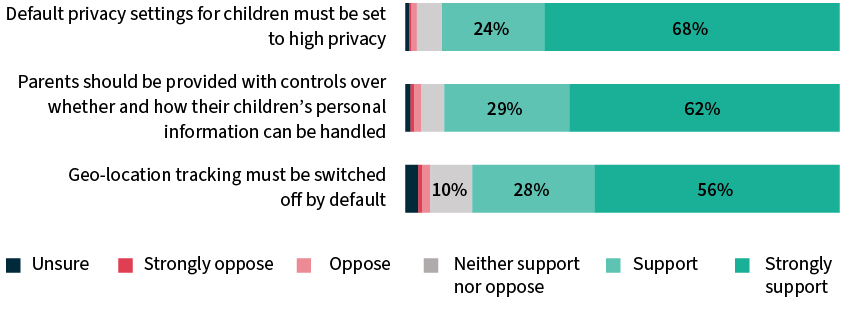

The vast majority of parents support organisations adopting a child-centric approach to handling personal information about children. This includes organisations considering what is in the best interests of children when handling their personal information (93% support) and providing important data privacy information to children in clear language that is not misleading (91% support).

Part 1: Introduction to privacy

Australians understand why they should safeguard their personal information and care enough about their privacy to do something about it, taking a variety of actions to protect themselves.

At the same time, only half of people say they have a clear understanding of how to protect their personal information, and only a third feel in control of their privacy.

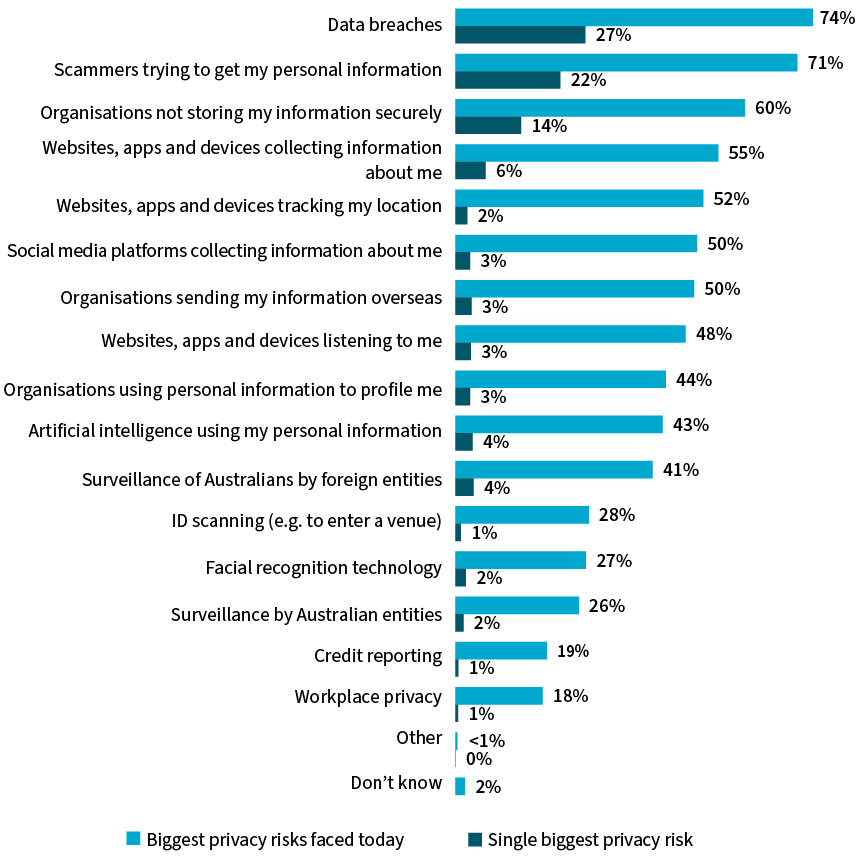

People are mainly concerned about data breaches and organisations not storing their personal information securely, as well as scammers trying to get their personal information.

Australians see privacy as important when they are looking to purchase products and services, rating it as the third most significant factor after quality and price.

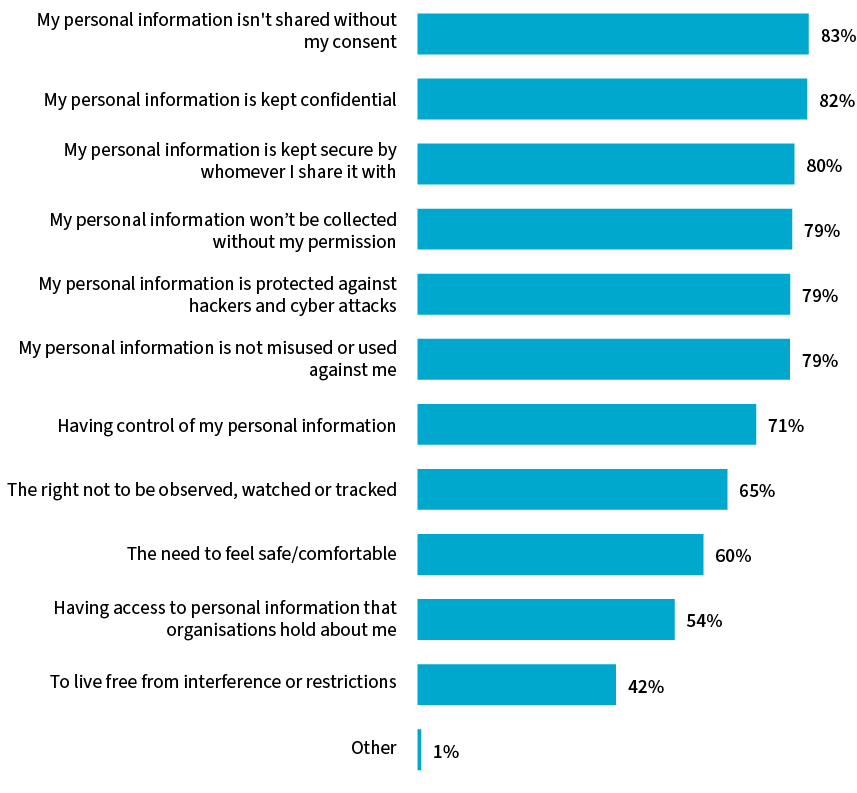

What privacy means to Australians

Primarily, when Australians think about the privacy of their personal information, they identify a framework for how their information should be handled by others. Most Australians consider privacy to mean their information is kept confidential and secure, not collected without their permission and not used against them.

Figure 1: What privacy means to Australians

G1. Thinking specifically about your personal information, what does ‘privacy’ mean to you. Select all that apply. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Older Australians are more likely to express a wider range of ideas when defining privacy. Those aged 65 and over are significantly more likely to select more responses to the question compared to the those aged under 65 (8.8 responses on average for 65+ years, cf. 7.7 for 35–64 years, 7.1 for 18–24 years).

Age also impacts people’s definition of privacy. Ninety-one per cent of people aged 65 and over say privacy should mean their information is not shared without their consent, compared to 84% of those aged 35 to 64 and 76% of those aged 18 to 34.

Similarly, 89% of people aged 65 and over define privacy as their information being kept confidential, compared to 82% of those aged 35 to 64 and 78% of those aged 18 to 34.

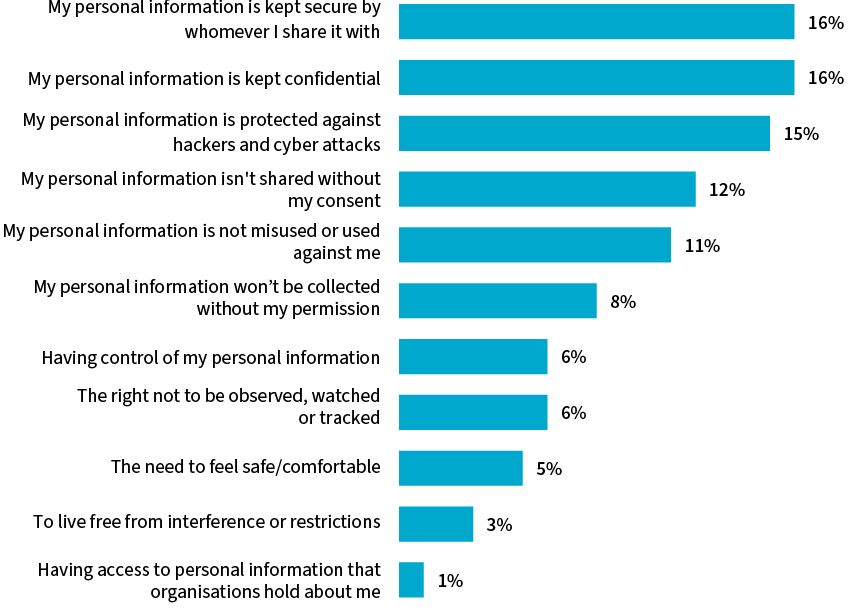

From the initial list of definitions, respondents were then asked to select the aspect of privacy of most importance to them.

This elevated the significance of the protection of personal information, with the key definitions selected being the need for their personal information to be kept secure, confidential and protected against hackers and cyber attacks, with 47% of Australians choosing one of these 3 options.

Figure 2: The most important aspects of privacy

G2. And which one is the most important to you? Select one. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Australians hold consistent views on the most important aspects of privacy, with no significant variation based on their age, gender or other demographics.

Watch our video where 5 Australians share their views on what privacy means to them.

Beliefs about protecting personal information

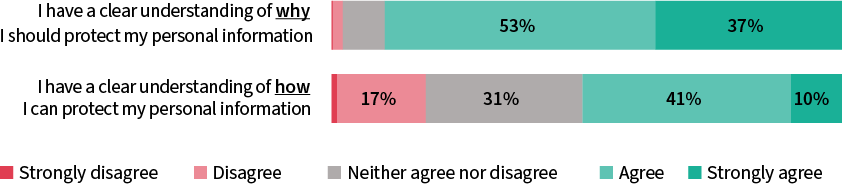

Nine out of ten (90% ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’) Australians say they have a clear understanding of why they should protect their personal information, but only half (51% ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’) understand how they can protect it.

This creates a gap of 39% between those who understand why they should protect their personal information and those who know how.

The proportion of people who understand why they should protect their information increased from 85% in 2020, while the understanding of how to protect their information remained relatively steady (51%in 2023, cf. 49% in 2020).

Figure 3: Beliefs about protecting personal information

G4. Thinking about data privacy, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

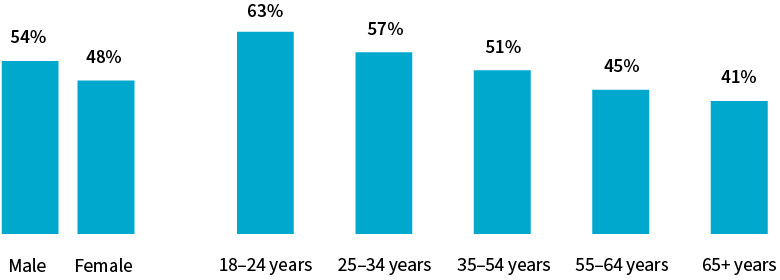

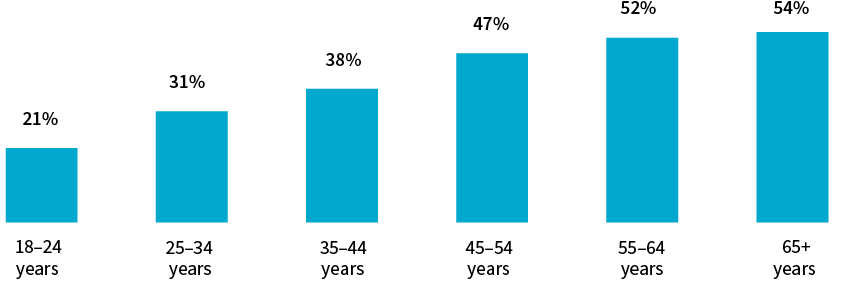

Younger Australians are more likely to consider they know how to protect their personal information compared to older age groups (63% ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ 18–24 years, cf. 41% 65+ years).

Males are more likely to say they know how to protect their privacy than females (54% ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ males, cf. 48% females).

Figure 4: Percentage that understand how to protect personal information by gender and age

G4. Thinking about data privacy, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following: I have a clear understanding of how I can protect my personal information? ‘Agree’ and ‘strongly agree’. Base: Australians 18+ years, males (n=936), females (n=978), 18–24 years (n=211), 25–34 years (n=352), 35–54 years (n=677) 55–64 years (n=278), 65+ years (n=398)

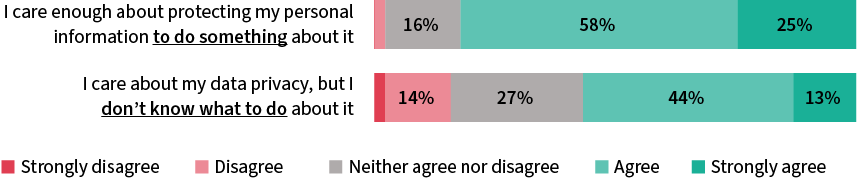

There was an increase in the proportion of Australian adults (82% in 2023, up from 75% in 2020) who care enough about protecting their personal information to do something about it. However, 3 out of 5 (57%) said they care about their data privacy, but do not know what to do about it.

Figure 5: Concern about protecting personal information

G4. Thinking about data privacy, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Similar to the beliefs around protecting their information, females are more likely than males to acknowledge they do not know what to do to protect their personal information (60% females, cf. 53% males). This data should be considered in the context of males claiming a higher level of privacy knowledge than females, while scoring lower when tested.

Beliefs around control over personal information

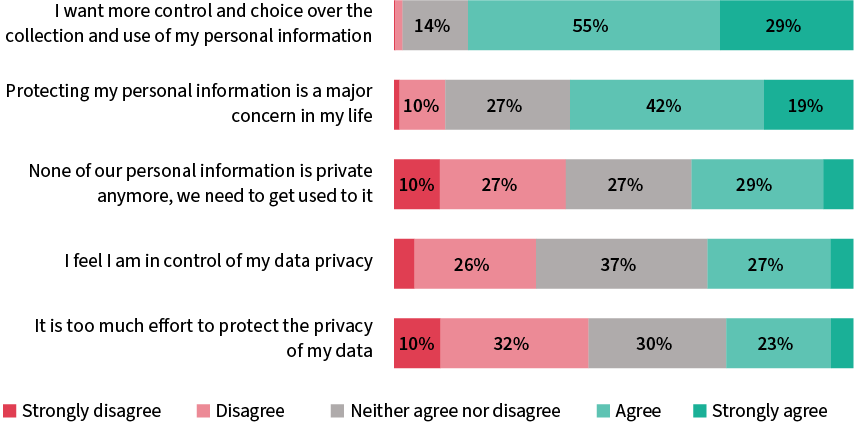

More than 4 out of 5 (84%) Australians want more control over the collection and use of their personal information, and this proportion is consistent across all demographic segments. This is a slight decline from 2020 when 87% ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ with this statement.

Three out of five (62%) said protecting their personal information is a major concern in their life.

Figure 6: Beliefs around control over personal information

G5, G6. Thinking about data privacy, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Younger Australians are most likely to feel in control of their data privacy (40% 18–34 years ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 32%), but often find it is too much effort to protect the privacy of their data (35% ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 28%).

Older Australians are least likely to feel in control of their data privacy (25% 55+ years ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 32%) and are less likely to say it is too much effort to protect their data (19% 55+ years ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 28%).

People aged 35 and older have an increasing perception of wanting more control and choice over the collection and use of their personal information (86% 35+ years ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 84%).

Knowledge of privacy rights

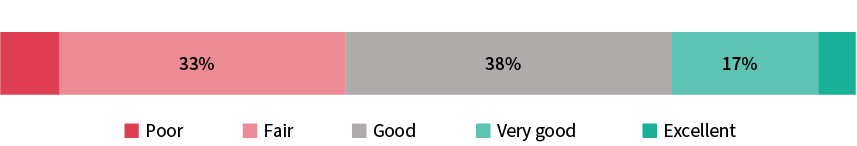

One in five (21%) Australians claim to have ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ knowledge of data protection and privacy rights, down slightly from 23% in 2020.

Figure 7: Self-rated knowledge of data protection and privacy rights

G3. Before today, how would you rate your knowledge of data protection and privacy rights? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

The perceived level of knowledge decreases with age, with younger adults claiming to have the most knowledge (29% 18–24 years claim ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ knowledge, cf. 13% 65+ years).

Males are also more likely to claim a better understanding of privacy rights, with 26% saying they have ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ knowledge (cf. 17% females).

Self-rated early adopters of technology are also more likely to claim a better understanding of privacy rights compared to the rest of the population. Sixty-six per cent of people who said they are ‘generally the first to try a new technology product’ stated they have ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ knowledge, compared to 21% of those who said they are ‘generally the last to try a new technology product’.

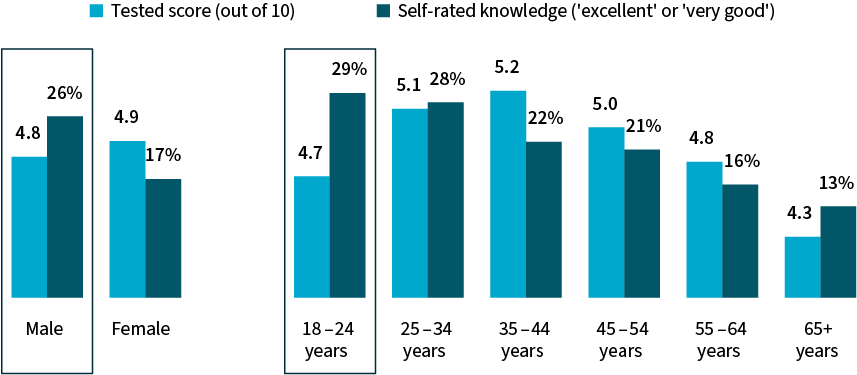

In addition to being asked to self-rate their knowledge of privacy rights, respondents were tested on their understanding of organisations’ obligations under the Australian Privacy Act.

Respondents were shown 10 statements and were asked to indicate whether each statement was true, false or they did not know either way. Out of the 10 statements, 7 were true and 3 were false. This was not disclosed to the respondent, and the order of the statements was randomised for each person.

Figure 8: Self-rated and tested knowledge of privacy rights by gender and age

G3. Before today, how would you rate your knowledge of data protection and privacy rights? ‘Very good’ or ‘excellent’.

G14. Thinking about your privacy rights, which of the following do you think are true and which are false? Respondents were show 10 statements about organisations’ responsibilities under the Australian Privacy Act.

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Respondents who had completed higher education and those with annual household incomes over $100,000 scored higher on average when tested.

People who classed themselves as early adopters of technology also scored higher on average than those who are the least likely to try new technology products, in line with the self-rated scores.

However, when viewed by respondent age and gender, there was disparity between the self‑rated and tested results.

Younger Australians (18–24 years) rated their knowledge the highest (29% claiming ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ knowledge), but scored lower than most other age groups.

A similar discrepancy exists between males and females, with males claiming a higher level of knowledge than females (26% males claiming ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ knowledge, cf. 17% females), but with the tested scores coming in almost on par (4.8 males, cf. 4.9 females).

Actions Australians take to protect their privacy

Out of concern for their data privacy, the 2 most common steps Australians take are checking an email, text message or phone call is not a scam before providing their information and using unique passwords and not sharing them.

Figure 9: Actions Australians always or often take out of concern for their data privacy

G8, G9 and G10. How frequently do you do the following out of concern for your data privacy. ‘Always or often’. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

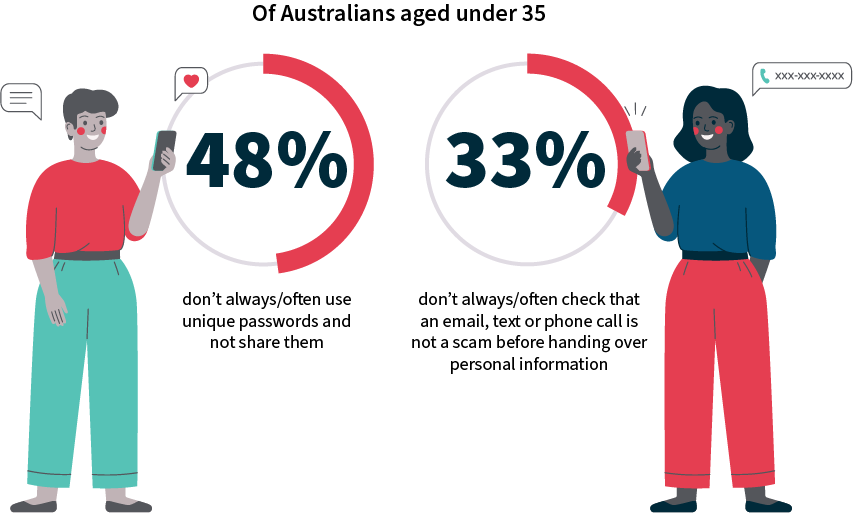

Both precautions are more likely to be taken by older Australians, with younger adults less likely to engage in these practices. Eighty-seven per cent of Australians aged 55 and older are ‘always or often’ taking precautions against scams, compared to 66% of those aged under 35. Similarly, 76% of Australians aged 55 and older ‘always or often’ use unique passwords compared to half (52%) of people under 35.

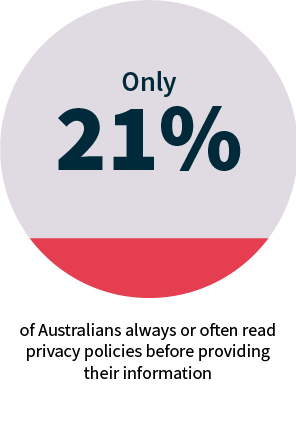

People under 35 are also less likely to read privacy policies before providing information compared to older Australians (17% <35 years, cf. 26% 65+ years).

Males and females also differ slightly in the way they protect their information. Females are more likely to check for scams before handing over information (80% females, cf. 71% males) and are also more likely to turn off GPS or location sharing (36% females, cf. 26% males) and ask websites, apps and devices not to track them when prompted (41% females, cf. 33% males).

Perceived privacy risks

Australians view data breaches and scammers as the top privacy risks they face.

Three-quarters (74%) of Australians feel data breaches are one of the biggest privacy risks they face today. This has increased by 13 percentage points since 2020 and is the most selected single biggest risk to privacy (27%).

Figure 10: Perceived privacy risks

P1. What do you think are the biggest privacy risks that you face today? Select all that apply.

P2. And of these, which one do you think is the biggest privacy risk? Select one.

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

Concern about the risk of data breaches increases to 78% for Australians aged 35 and over, compared to 66% among those aged 18 to 34.

Seven in ten (71%) Australians say one of their biggest concerns is scammers trying to trick them into giving out personal information. This increases to 83% among Australians aged 55 and over, compared to 61% of those aged 18 to 34. One in five (22%) consider scammers the single biggest risk to privacy.

Watch our video where 5 Australians discuss their feelings about these risks and other privacy concerns they have.

Role of privacy in purchasing decisions

Most Australians place a high level of importance on their privacy when choosing a product or service, with 70% saying it is ‘extremely’ or ‘very important’ and another 26% stating it is ‘quite important’.

Figure 11: Importance of privacy when choosing a product or service

F9. Overall, how important is the privacy of your information when choosing a product or service? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Australians aged 18 to 34 are less likely to consider privacy ‘extremely important’ compared to those aged 45 and older (29% 18–34 years, cf. 43% 45+ years). This is in line with the younger cohort’s indifference towards taking measures to protect themselves, including regularly changing passwords and checking communications are not scams before interacting with them.

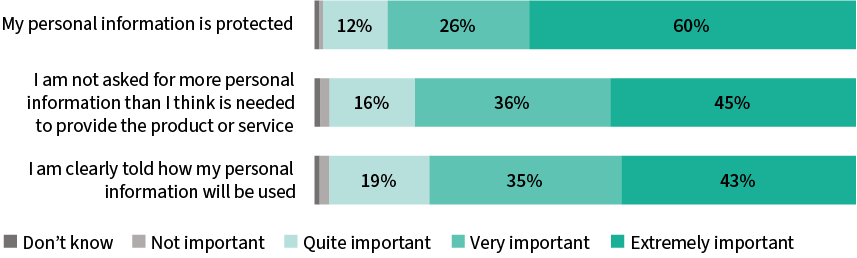

The most important aspect of privacy Australians consider when selecting a product or service is that their information is protected. Three in five (60%) Australians say this component is ‘extremely important’ for them, with a further quarter (26%) saying it is ‘very important’.

Four in five Australians place high importance on not being asked for more personal information than they think is needed to provide the product or service (81% ‘extremely’ or ‘very important’) and being clearly told how their personal information will be used (79% ‘extremely’ or ‘very important’).

Figure 12: Influences of privacy practices on choosing products and services

F10. How important are the following when choosing a product or service? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Females are more likely to place higher importance on the protection and amount of information required compared to males (information protected 89% ‘extremely’ or ‘very important’ for females, cf. 84% males; amount of information 84% females, cf. 79% males).

Figure 13: Influences of privacy practices by age group

F10. How important are the following when choosing a product or service? ‘Extremely important’ and ‘very important’. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

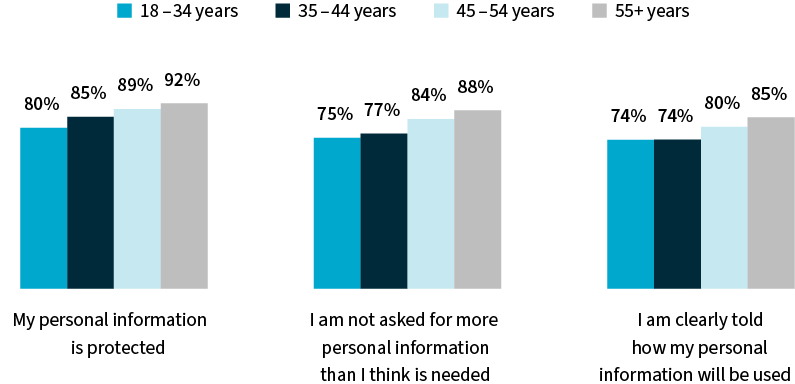

As with other privacy measures, the importance when choosing a product or service of how data is collected, used and protected varies with age. Younger Australians still place a great deal of emphasis on privacy practices when choosing a product or service, with around three-quarters of those aged 18 to 34 indicating the aspects tested have a high level of importance to them.

However, as age increases, so does the importance of these privacy practices. For people aged 45 and over, there is a significant increase in the importance of their personal information being protected, not being asked for more information than they consider necessary and being clearly told how their information will be used.

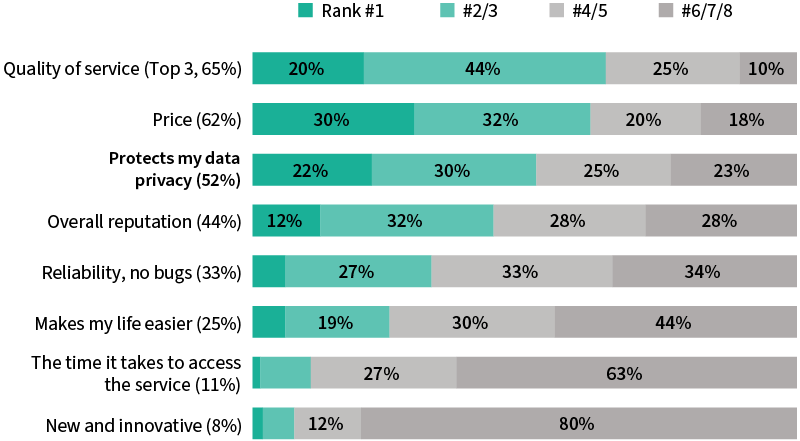

Where privacy sits among other purchase factors

Quality and price are the key considerations for Australians when choosing a product or service. Half of Australians (52%) ranked data privacy in their top 3 considerations.

Privacy is seen as more important than ‘makes my life easier’ and ‘the time it takes to access the service’, indicating many people are prepared to experience some inconvenience in exchange for their privacy being protected.

Figure 14: Important factors when choosing a product or service

F8. Please rank each of the following in order of importance when choosing a product or service. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Younger age groups and males are less likely to rank privacy as high as older age groups and females, but regardless of demographic profile, it remains in the top 3 considerations for all segments.

Among Australians aged 65 and over, privacy becomes more important than price (63% ranked privacy in the top 3, cf. 57% price).

Part 2: Privacy legislation

Australians have low awareness of privacy legislation, notably around their rights to access information organisations hold about them and organisation types that are exempt from the Australian Privacy Act.

Most want more rights to control the way their personal information is collected, used and stored.

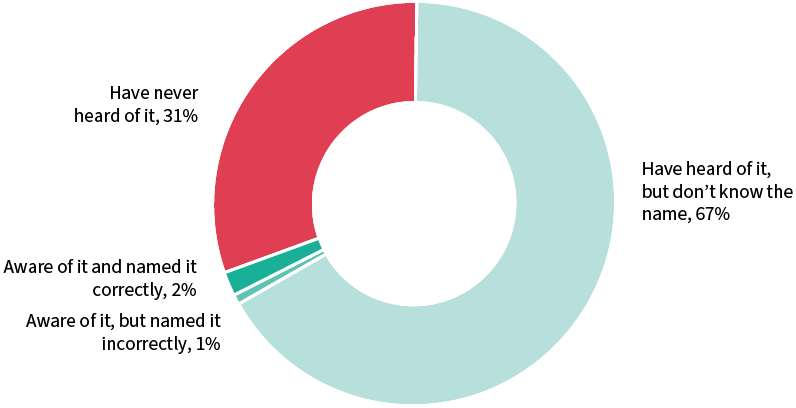

Awareness of the Privacy Act

Seven in ten (69%) Australians said they are aware of the Australian privacy law that promotes and protects the privacy of individuals, a 3 percentage point increase from 2020, but only 2% correctly named it as the ‘Privacy Act’ or ‘Australian Privacy Principles’.

Figure 15: Awareness of the Privacy Act

G11. Are you aware of the Australian privacy law that promotes and protects the privacy of individuals? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Australians aged 18 to 24 are the least likely to be aware of the Privacy Act, with 2 out of 5 (42%) saying they have never heard of it.

People in full-time employment have a higher awareness than the average Australian (70%), as do those who have completed a bachelor’s degree or post-graduate qualification (72%) and early adopters of technology (70%).

Awareness and engagement with the Privacy Commissioner

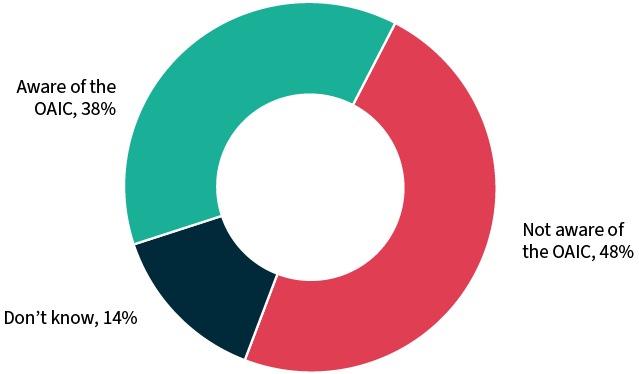

Awareness of the Privacy Commissioner has decreased 10 percentage points since 2020 (38% in 2023, cf. 48% in 2020, 44% in 2017). However, the wording of the question in the 2023 survey changed slightly to include a reference to the ‘Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’, making statistical tracking of this measurement unpredictable.

Figure 16: Awareness of the Privacy Commissioner (OAIC)

G12. Are you aware that the Privacy Commissioner (the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner) exists to uphold privacy laws and to investigate complaints about the misuse of personal information? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Males are more likely to be aware of the OAIC than females (41% males, cf. 35% females). There is also higher awareness of the OAIC among Australians who have completed tertiary education and who are tech savvy.

Twenty-nine per cent of Australians with no tertiary education are aware of the OAIC, compared to 44% of those with a bachelor’s or postgraduate qualification. Thirty per cent of people who consider themselves to be late adopters of technology are aware of the OAIC, compared to 53% for early adopters.

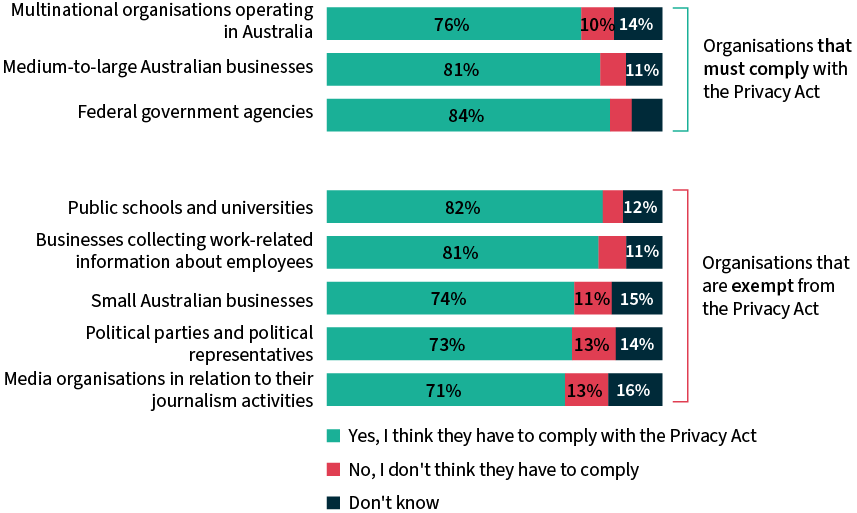

Awareness of organisation types covered by the Privacy Act

Australians have limited understanding of which organisation types have to comply with the Privacy Act.

Federal government agencies, medium-to-large Australian businesses and multinational organisations operating in Australia have responsibilities under the Act. Public schools and universities, businesses collecting work-related information about employees, small Australian businesses (with a turnover of less than $3 million), political parties and representatives, and media organisations in relation to their journalism activities do not.

Most Australians think all organisation types tested are covered by the Privacy Act.

Figure 17: Awareness of organisation types covered by the Privacy Act

L1. The Australian Privacy Act determines how organisations must handle your personal information. Which of the following do you think have to comply with the Privacy Act? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

The organisation type most likely to be incorrectly identified as having to comply with the Privacy Act is public schools and universities (82%), however public schools and public universities may be covered under state or territory privacy legislation. Parents of children aged 2 to 17 are more likely to believe public schools and universities are covered (86%) compared to those without children in this age bracket (80%).

Awareness of exempt organisation types has decreased from 2020. In 2023, the proportion of people who could correctly identify exempt organisation types ranged between 6% and 13%, compared to between 12% and 17% in 2020.

The majority of people thought the exempt organisation types were covered by the Privacy Act, which is consistent with a population simply assuming most organisations are covered.

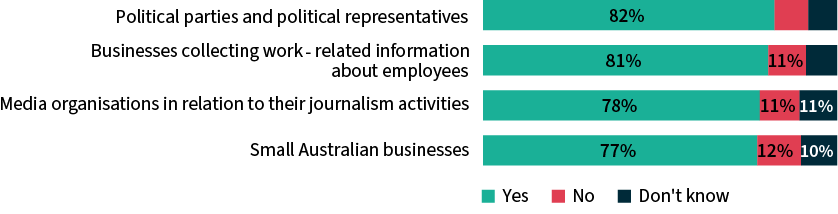

Belief that organisation types should be covered by the Privacy Act

Four out of five people feel political parties and representatives (82%), businesses collecting work‑related information about employees (81%) and media organisations in relation to their journalism activities (78%) should be required to protect personal information in the same way as federal government agencies and larger businesses. Three-quarters (77%) of Australians feel the same about small business.

Figure 18: Belief that organisation types should be covered by the Privacy Act

L2. The following sectors are currently exempt from the Australian Privacy Act. Should they have to handle your personal information in the same way as federal government agencies and larger businesses? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

People aged 35 and over are more likely than younger Australians to think small businesses and businesses collecting work‑related information about employees should be held to the same standards as larger businesses and government agencies (small businesses 80% 35+ years, cf. 71% 18–34 years; businesses collecting work-related information 83% 35+ years, cf. 75% 18–34 years).

The proportion of people who think all specified organisation types should not have the same obligations as federal government agencies and larger businesses has not changed significantly since 2020. However, fewer people responded ‘don’t know’, resulting in a higher proportion of people in favour of removing the exemptions.

The share of people who think political parties and representatives should be held to the same standards as federal government agencies and larger business increased from 74% in 2020 to 82% in 2023, and for businesses collecting work-related information went from 73% to 81%. Media organisations and small businesses saw a 6 percentage point increase (media organisations 78% in 2023, cf. 72% in 2020; small businesses 77% in 2023, cf. 71% in 2020).

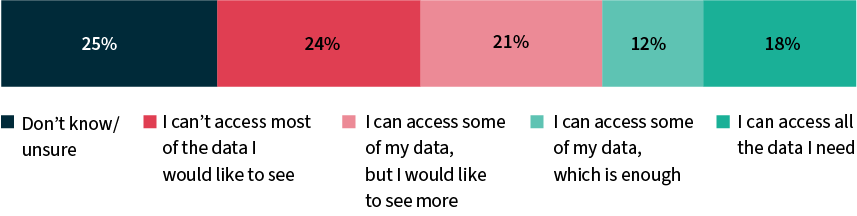

Extent Australians can access and use data

Only 3 in 10 (30%) Australians are satisfied that they can access and use the data organisations hold about them.

A quarter (25%) of Australians do not know or are unsure about the extent they can access and use data organisations hold about them, and a quarter (24%) say that they cannot access most of the data they would like to see. A further fifth (21%) say they can access some of their data, but would like to see more.

Figure 19: Extent Australians can access and use data

L3. To what extent do you feel you can access and use the data organisations hold about you (e.g. your account and transaction/usage data held by banks, energy providers and telcos)? Select one. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

Dissatisfaction is similar across age and gender, however satisfaction is higher among those aged 18 to 34 compared to those aged 35 and older (can access all the data they need or some data, which is enough 37% 18–34 years, cf. 26% 35+ years).

Australians aged 35 and older are twice as likely as those aged 18 to 34 to not know the extent to which they can access and use their personal data (30% 35+ years, cf. 15% 18–34 years).

Access to personal information

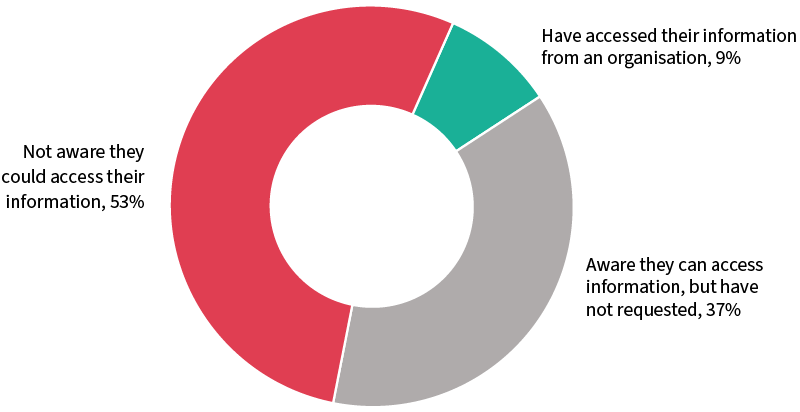

Less than half (47%) of Australians are aware they can request to access their personal information from an organisation, and only 1 in 10 (9%) Australians have requested access.

Figure 20: Access to personal information held by organisations

L4. Are you aware that you can request to access your personal information from organisations?

L5. Have you ever requested to access your personal information from an organisation?

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

Half (51%) of males are aware they can request access, compared to 43% of females. Similarly, 52% of those aged 18 to 34 are aware compared to 44% for those aged 35 and over.

Australians aged 18 to 34 are twice as likely as people aged 35 and over to have made a request (15% 18–34 years, cf. 7% 35+ years). Age differences become even greater when comparing the youngest and oldest cohorts, with 16% of those aged 18 to 24 having requested access to personal information from organisations compared to 4% of those aged 65 and older.

Additional rights under the Privacy Act

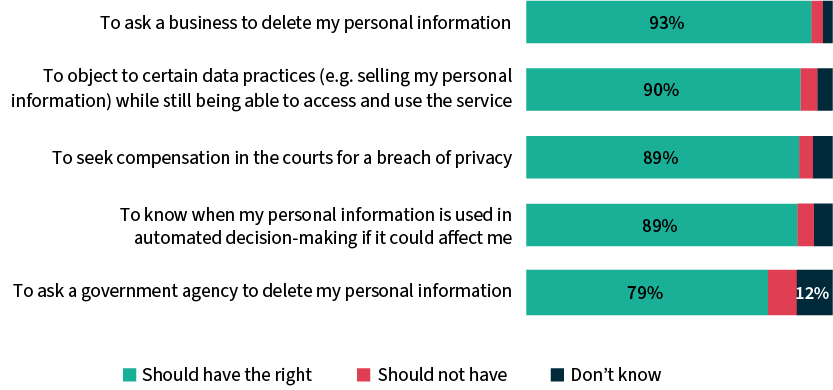

Australians strongly believe they should have extra rights under the Privacy Act.

They are most likely to believe they should have the right to ask a business to delete their personal information (93%). This has strong and consistent support across age groups and genders.

Nine in ten Australians say they should have the right to object to certain data practices while still being able to access and use a service (90%), to seek compensation in the courts for a breach of privacy (89%) and to know when their personal information is used in automated decision-making if it could affect them (such as when information about their race is used to determine what information they see in their social media feed) (89%).

Figure 21: Beliefs that Australians should have specific privacy rights

L6. Do you believe you should have these rights under the Australian Privacy Act? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

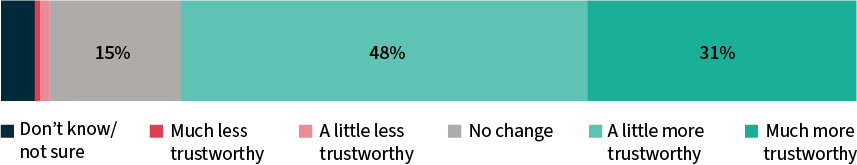

Privacy certification

A privacy certification system, where an independent body rates how well an organisation protects personal information, would make certified organisations more trustworthy to 4 in 5 (79%) Australians.

Figure 22: Impact of privacy certification on trust in organisations

L7. Consider if a privacy certification system was introduced in Australia, where an independent body rates how well an organisation protects your personal information. To what extent would this make certified organisations more or less trustworthy? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

Females would see certified organisations as more trustworthy than males (83% females, cf. 75% males).

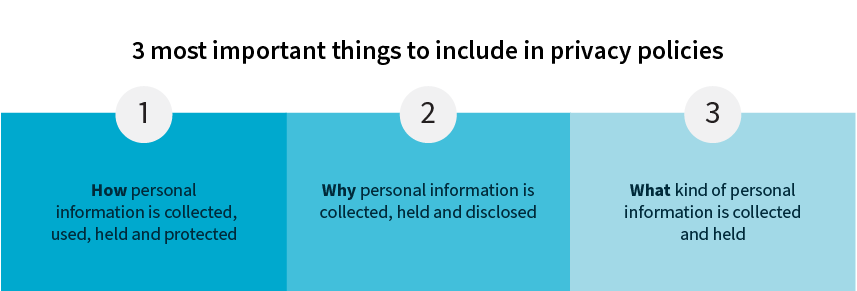

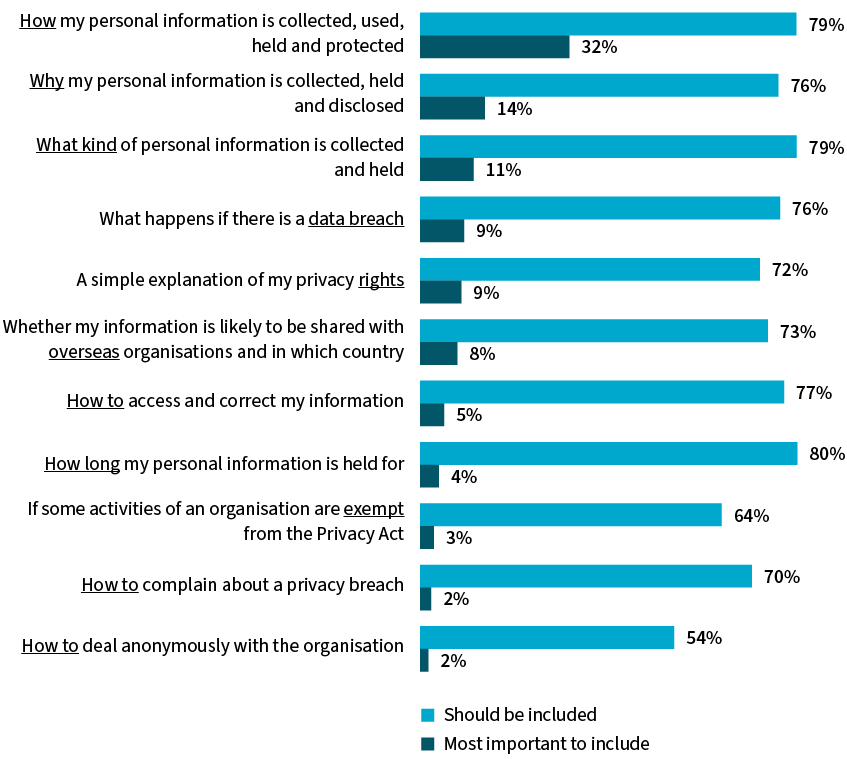

Desired content in privacy policies

Australians want a wide range of information to be included in privacy policies. Of the options provided, ‘how my personal information is collected, used, held and protected’ is the ‘most important’ inclusion for a third (32%) of people.

There is also a strong desire for transparency around ‘why’ the data is being collected, held and disclosed (14% most important), as well as ‘what kind’ of information is being collected and held (11% most important).

Three in ten (29%) Australians believe all aspects listed should be included in privacy policies. Among this cohort, 35% believe ‘how’ the information is collected, used, held and protected is the most important thing to include.

Figure 23: Desired content in privacy policies

L8. Some people think that privacy policies should be as short as possible, others think they should be comprehensive. With this in mind, which of the following do you think should be in all privacy policies? Select all that apply.

L9. Which of the following do you think is the most important thing to be in all privacy policies? Select one.

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

Australians aged 18 to 34 are nearly twice as likely as people aged 35 and over to say a simple explanation of their privacy rights is the most important inclusion (13% 18–34 years, cf. 7% 35+ years).

Part 3: The role of organisations

Australians want organisations to do more to protect their data and be transparent about what they do with their personal information. They frequently do not know what organisations do with their data and often feel they have no choice but to hand over personal information if they want to access a service.

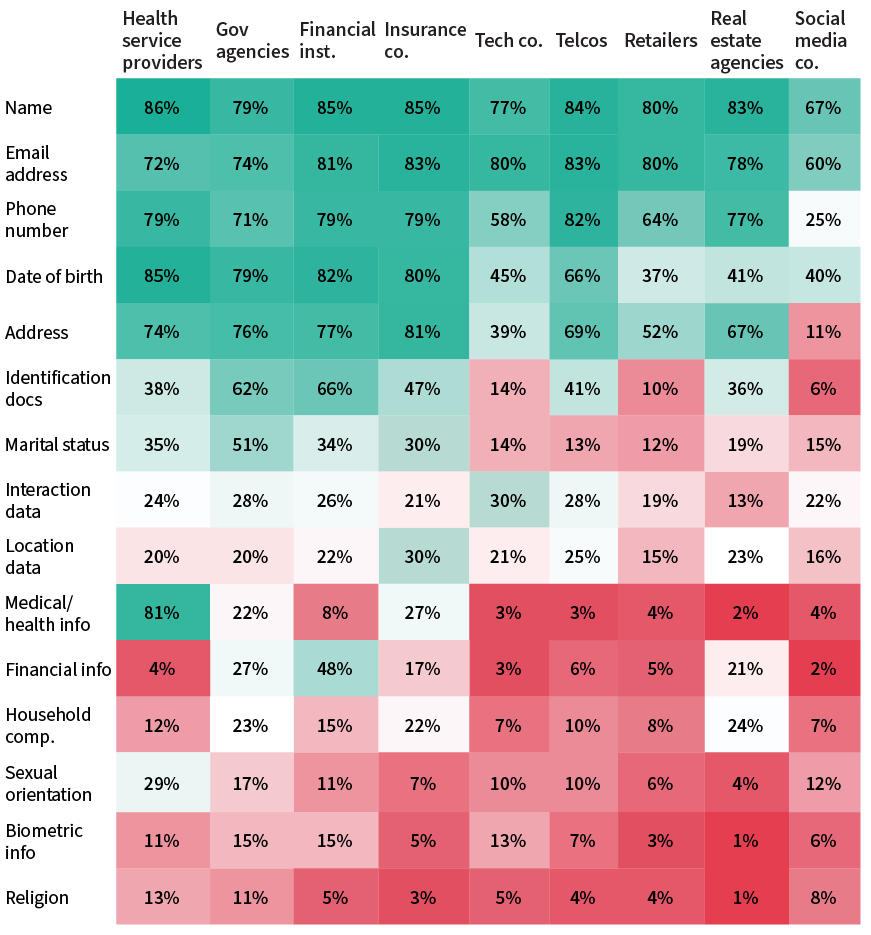

While most Australians expect they might need to share some level of personal information to access a service, they generally only consider it fair and reasonable to provide their name and email address. The information considered fair and reasonable to provide varies by how trustworthy they consider the industry sector to be.

Health service providers and federal government agencies are generally considered the most trustworthy organisations when it comes to handling personal information, while social media companies and real estate agencies are the least trusted.

Most Australians are concerned about the prospect of their personal data being sent overseas, and the level of concern increases with age. It is also reflected in the trust associated with where an organisation is based. Australian businesses are more trusted than those based overseas, even if they have a presence in Australia.

Watch our video where 5 Australians share their thoughts on how organisations protect personal information.

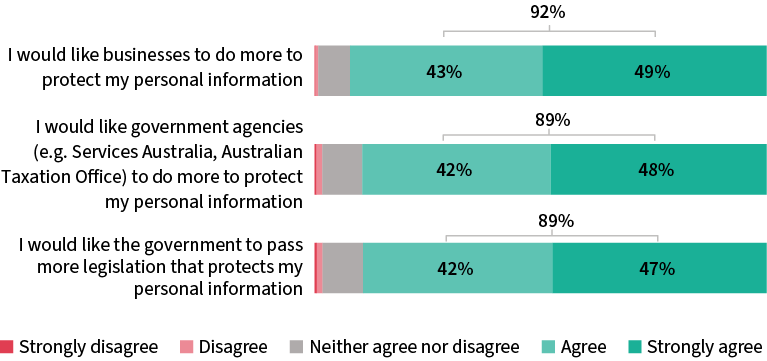

Responsibility for protecting personal information

While many Australians do not know exactly how they can protect their own personal information, the majority would like organisations to do more in this area.

There is a common view that businesses should do more to protect Australians’ personal information (92% ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’), as should government agencies (89%).

Nine in ten (89%) respondents would like government to pass more legislation that protects their personal information.

Figure 24: Beliefs that organisations should do more to protect personal information

G7. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? ‘Agree’ and ‘strongly agree’. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

The only significant variation in this view lies with Australians aged 18 to 24, who see a similar need for government to pass more legislation to protect them (87%), but are less likely to expect businesses (84%) and government agencies (82%) to do more.

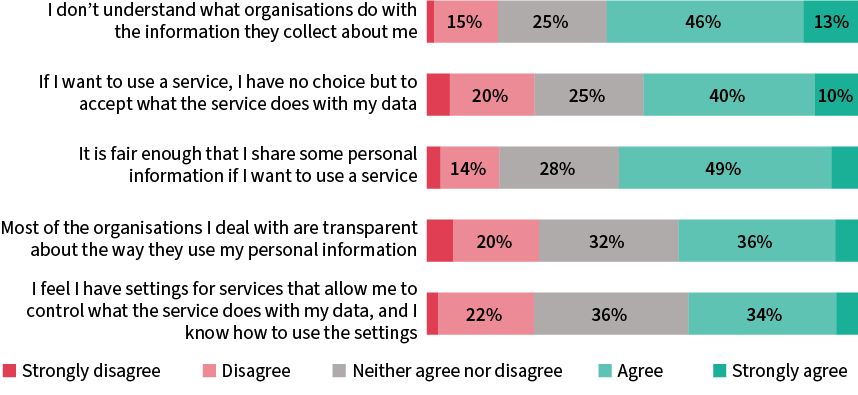

Beliefs about organisations’ personal information handling practices

Three in five (58% ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’) Australians do not understand what organisations do with the information that is collected about them.

Around half of people agree it is fair enough to share some information to use a service (55% ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’), but a similar proportion (50%) feel they have no choice but to accept what a service does with their data.

Figure 25: Beliefs about organisations’ personal information handling practices

G6. Thinking about data privacy, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,916)

Australians aged 25 to 34 are more likely to believe if they want to use a service, they have no choice but to accept what the service does with their data (58% ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 50%).

Those aged 18 to 34 are more likely to feel they are able to control what the service does with their data through the use of settings (50% ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, cf. average 39%).

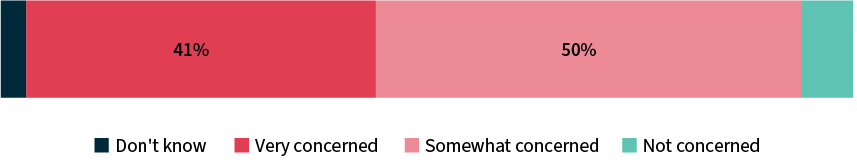

Concern about information being sent overseas

Most Australians (91%) are concerned about organisations sending their customers’ information from Australia to overseas, with 2 in 5 (41%) ‘very concerned’. Only 6% of people are ‘not concerned’.

Figure 26: Concern about organisations sending personal information overseas

F4. How concerned are you about organisations sending their customers’ personal information from Australia to overseas? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

The higher levels of concern about privacy among older Australians can also be seen in their attitude to organisations sending their customers’ personal information from Australia to overseas.

Over half (53%) of Australians aged 55 and over are ‘very concerned’ about Australians’ personal information being sent overseas, decreasing to 21% among people aged 18 to 24.

Figure 27: Concern about organisations sending personal information overseas by age

F4. How concerned are you about organisations sending their customers’ personal information from Australia to overseas? ‘Very concerned’. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

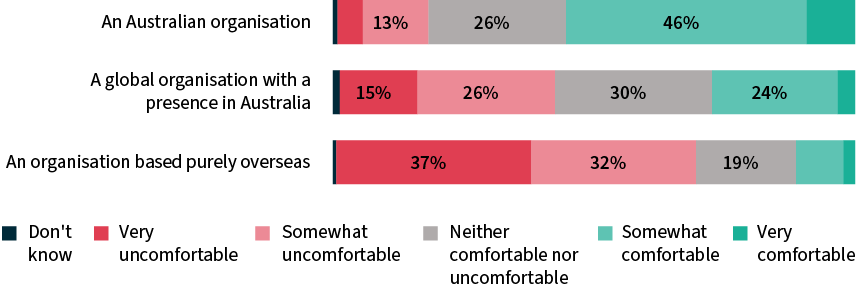

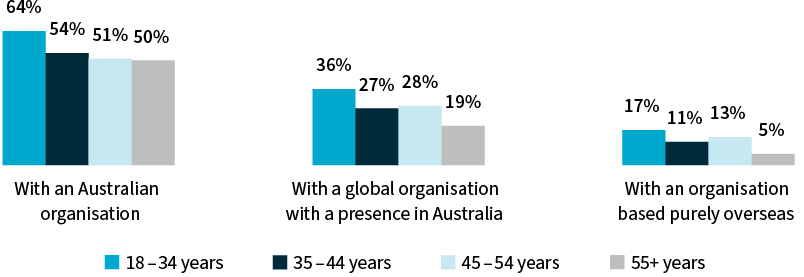

Comfort dealing with local vs overseas organisations

Most Australians (55%) are comfortable sharing their personal information with local organisations, but that level of comfort falls when dealing with overseas organisations, even if they have a local presence (27% global with an Australian presence, cf. 11% based purely overseas).

Figure 28: Comfort sharing personal information with local and overseas organisations

F5. How comfortable are you with sharing your personal information with the following? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Again, age has an impact on how at ease people feel. Australians aged 18 to 34 more likely to be comfortable sharing their data with local and overseas organisations (including those with a presence in Australia), although the majority (56%) are uncomfortable sharing data with an organisation based purely overseas.

Figure 29: Comfort sharing personal information with local and overseas organisations by age

F5. How comfortable are you with sharing your personal information with the following? ‘Very comfortable’ and ‘somewhat comfortable’. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

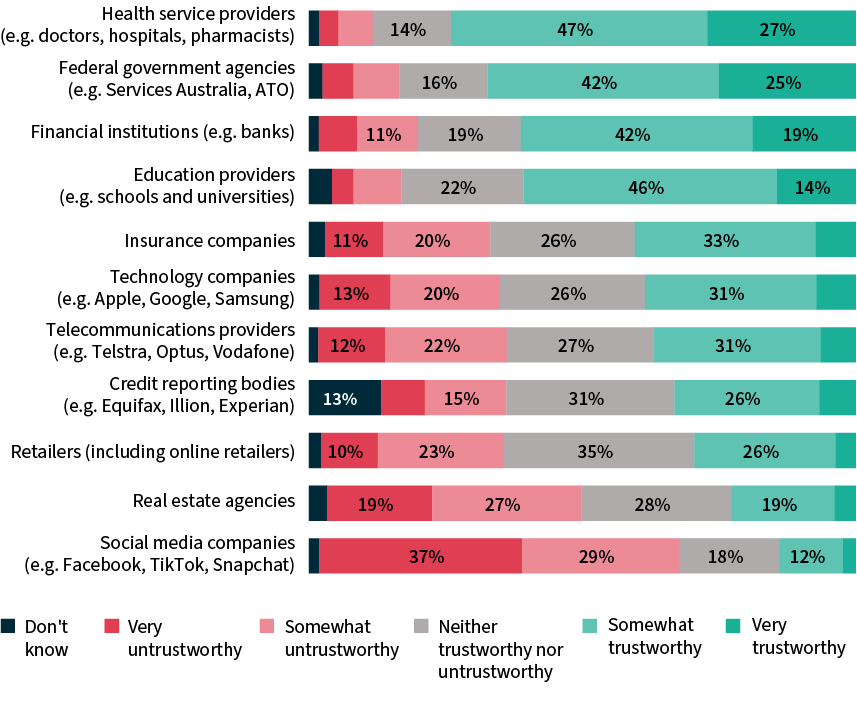

Trust in organisations

Trustworthiness by industry sector

Health service providers are the most trusted industry sector when it comes to the protection and use of personal information. This is especially true for older Australians, with those aged 55 and over more likely to rate health service providers as ‘very’ or ‘somewhat trustworthy’ (78% 55+ years, cf. 74% all adults).

Social media companies and real estate agencies are the least trusted industry sectors from the list surveyed. Two-thirds (66%) of Australians say they find social media companies to be ‘very’ or ‘somewhat untrustworthy’, with half (46%) saying the same of real estate agencies.

Figure 30: Trustworthiness by industry sector

F1. How trustworthy would you say the following organisations are with regard to how they protect and use your personal information? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Australians aged 55 and older are more likely to trust federal government agencies, financial institutions and telecommunications providers than the average person.

Australians under 35 are more likely to trust real estate agencies and social media companies than those aged 35 and older – although they still classify them as the least trustworthy on the list.

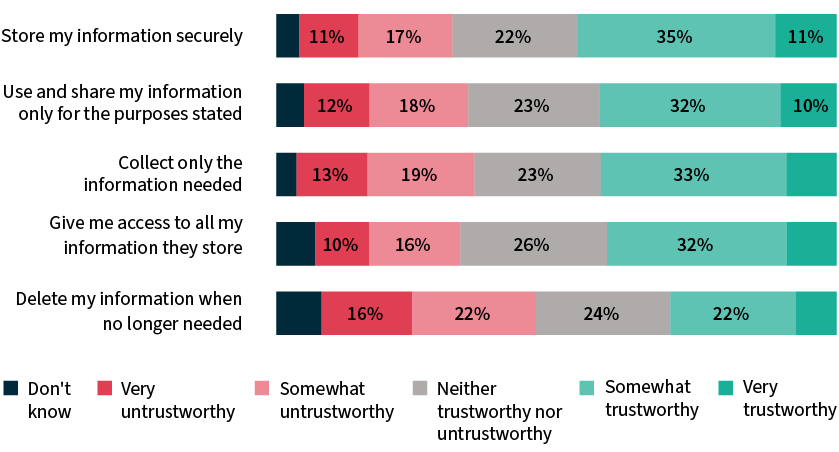

Trust in aspects of personal information handling

There is a high level of distrust that organisations will do the right thing by Australians when it comes to the handling of personal information. Less than half of people trust organisations to:

- store their information securely (46% ‘very trustworthy’ or ‘somewhat trustworthy’)

- use and share their information only for the purposes stated (42%)

- collect only the information needed (42%)

- give people access to all their personal information stored (41%)

- delete their information when no longer needed (30%).

Figure 31: Trust in aspects of personal information handling

F3. How trustworthy would you say <sector> are with regard to the following? Aggregated across 9 industry sectors. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

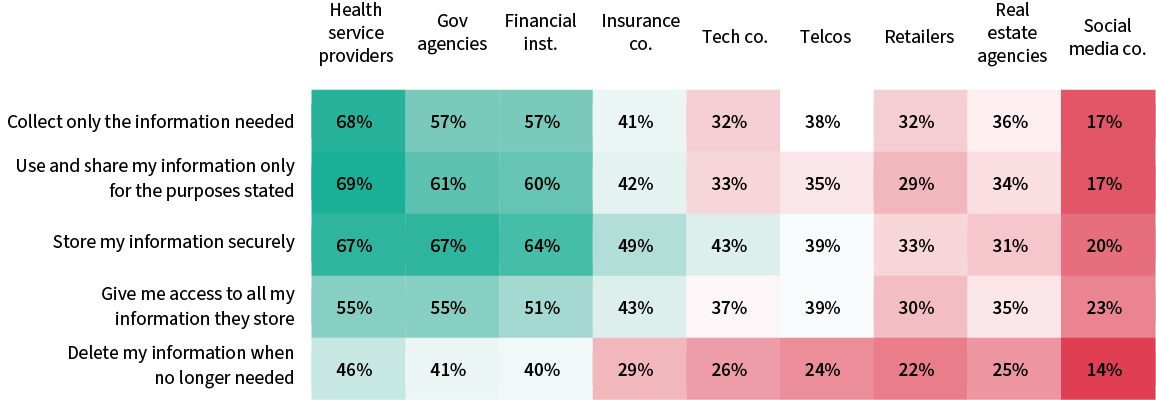

There is a widely held belief that health service providers, federal government agencies and financial institutions are trustworthy across most aspects of personal information handling tested.

Most sectors are not trusted to only collect the information they need, use and share information as they state, store information securely, give individuals access to their personal information and delete information when no longer needed. Retailers and social media companies are perceived as the least likely to do these things.

Figure 32: Trust in aspects of personal information handling by industry sector

F3. How trustworthy would you say <sector> are with regard to the following? ‘Very trustworthy’ and ‘somewhat trustworthy’. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Information considered fair and reasonable to provide

Australians are usually happy to divulge their name and email address when accessing a service, then, dependent on the type of organisation, generally consider providing their phone number, date of birth and address as fair and reasonable.

Figure 33: Information considered fair and reasonable to provide when accessing services

F2. What information would you consider to be fair and reasonable to provide <sector> when accessing services? Aggregated across 9 industry sectors. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

While the majority of Australians consider it fair and reasonable to supply their name, email, phone number, date of birth and address when accessing services, this varies by industry sector.

There is more reluctance to supply some of these details, especially date of birth, to technology companies, retailers, real estate agencies and social media companies.

While real estate agencies are generally viewed with distrust, Australians consider a range of information is fair and reasonable to provide to them.

Figure 34: Information considered fair and reasonable to provide when accessing services by industry sector

F2. What information would you consider to be fair and reasonable to provide to <sector> when accessing their services? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Government use of personal information for research and service and policy development

There has been a growing level of comfort with the government using personal information for research and service and policy development over the last 6 years.

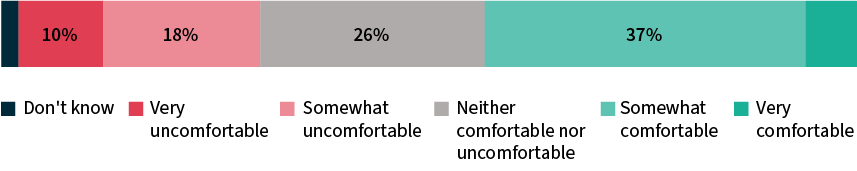

Around two-fifths (44%) of Australians are ‘very’ or ‘somewhat comfortable’ with the government using their personal information for research and service and policy development, up from 38% in 2017 and 40% in 2020.

Figure 35: Comfort with the use of personal information for government research and development

F7. How comfortable are you with the personal information that you’ve provided to government agencies being used for research, service development or policy development purposes? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

People aged 65 and older are more comfortable than the average Australian, with 53% ‘very’ or ‘somewhat comfortable’.

Beliefs about whether certain practices are fair and reasonable

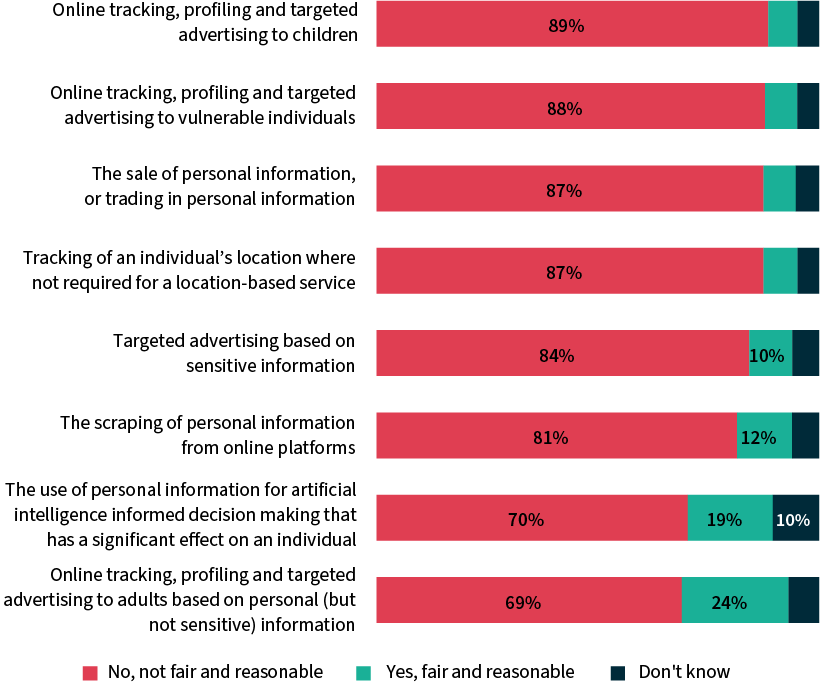

The definition of what is fair and reasonable can vary when it comes to the sharing of personal information, depending on the industry sector of the organisation the data is being shared with. However, there are some strong opinions around certain practices generally.

The majority of Australians consider the practices tested to be not fair and reasonable. The practices most likely to be considered ‘not fair and reasonable’ are the online tracking, profiling and targeting of advertising to children (89%) and vulnerable individuals (such as gambling companies targeting gamblers) (88%).

Figure 36: Beliefs about whether certain practices are fair and reasonable

F6. Do you consider the following to be fair and reasonable practices? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,642)

Part 4: Privacy breaches and harm

New to ACAPS for 2023 is this section on privacy breaches and associated harms.

Most Australians had an issue with how their personal information was handled and almost half were directly impacted by a data breach in the 12 months prior to completing the survey.

Three-quarters of those who were involved in a data breach said they experienced some form of harm as a result. The most common harm experienced was an increase in scams or spam emails and texts. One in ten experienced emotional or psychological harm.

Almost half of people say they would stop using a service if their data was involved in a breach, but this drops to a third for people who have recently experienced a breach.

When it comes to dealing with the impacts of a breach, only 1 in 10 people said there was nothing an organisation could do to appease them. Most Australians are willing to remain with an organisation that has experienced a data breach, provided the organisation quickly takes action, such as putting steps in place to prevent customers from suffering harm.

To protect their data, Australians want organisations to only collect the data they need, take proactive steps to protect personal information they hold, and delete it when it is no longer needed.

Privacy breaches

The term ‘privacy breach’ is used in this report to refer to a wide range of problems experienced with the handling of personal information. It is distinct from ‘data breach’ – respondents were shown a definition of ‘data breach’ before the relevant section of the survey.

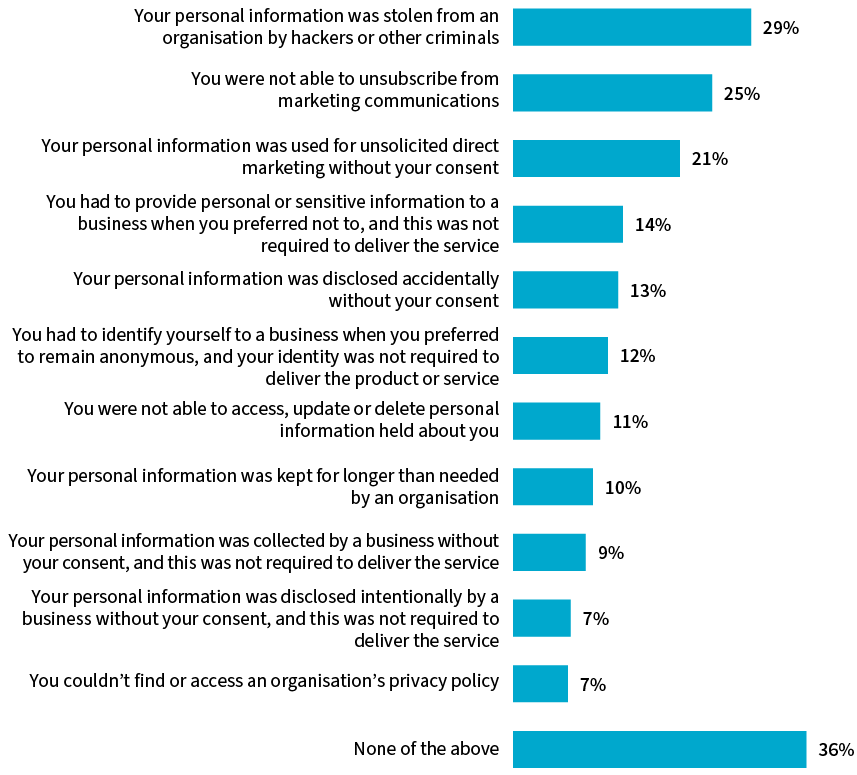

Problems experienced with the handling of personal information

Almost two-thirds (64%) of Australians experienced at least one problem with the handling of their personal information in the 12 months prior to completing the survey.

Figure 37: Problems experienced with the handling of personal information

P3. Have you experienced any of the following in the past 12 months. Select all that apply. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

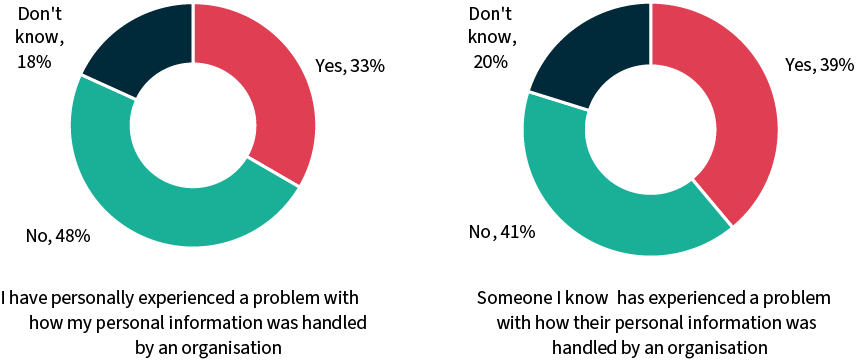

Incidence of privacy breaches

A third (33%) of Australians personally experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation in the 12 months prior to completing the survey. This drops to a quarter (26%) among Australians aged 65 and over, compared to 35% for those aged 18 to 64.

Figure 38: Incidence of privacy breaches

P4. In the past 12 months, have you personally experienced a problem with how your personal information was handled by an organisation?

P5. Has someone you know experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation?

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

Two in five (39%) Australians know someone who has experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation. Like personal experience, this is lower among those aged 65 and over (26%) compared to those aged 18 to 64 (42%).

A quarter (25%) of Australians have both had a problem with how their personal information was handled and know someone else who has experienced this.

Harms experienced from privacy breaches

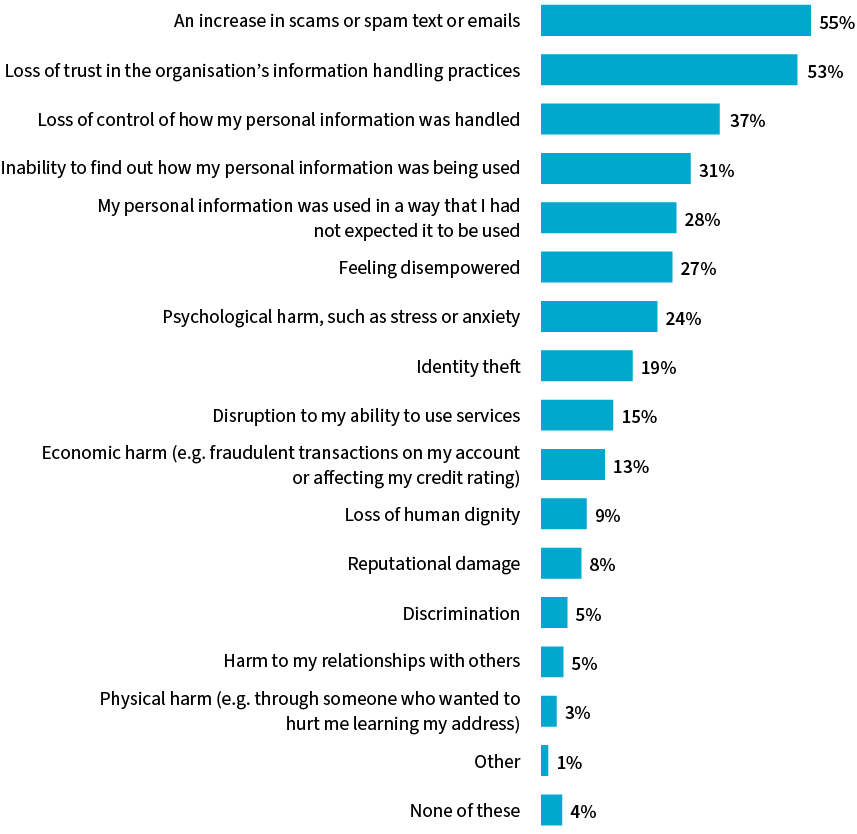

Among Australians who personally experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation in the 12 months prior to completing the survey, more than half (55%) reported an increase in scams or spam texts or emails. More than half (53%) said they lost trust in the organisation’s information handling practices.

Two in five (37%) experienced a loss of control of how their data was being handled, while nearly a third (31%) reported an inability to find out how their personal information was being used.

Figure 39: Harms experienced from privacy breaches

P6. Which of the following have you experienced because of a problem with how your personal information was handled by an organisation? Select all that apply. Base: Australians who have experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation (n=540)

More females reported an inability to find out how their information was being used than males (38% females, cf. 24% males). Females are also more likely to say they feel disempowered because of a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation (32% females, cf. 22% males).

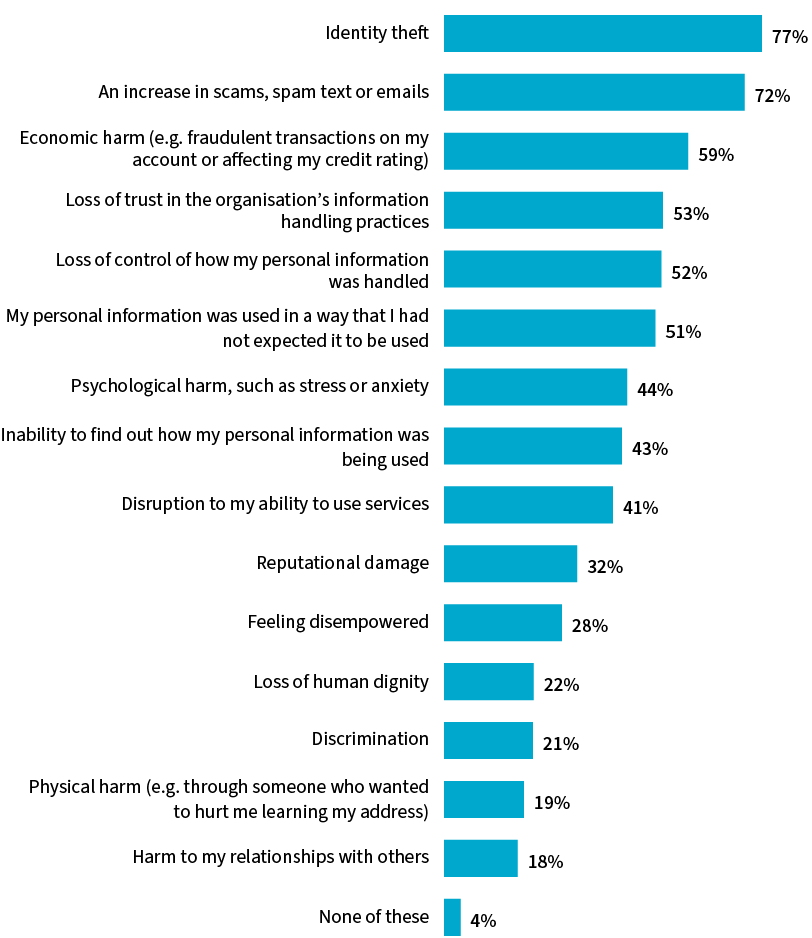

Harms Australians perceive could result from a privacy breach

Among Australians who had not experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation in the 12 months prior to completing the survey, around three-quarters believe identity theft (77%) and an increase in scams or spam texts or emails (72%) could result from their information being mishandled. The belief that identity theft could result from mishandled personal information increases with age (86% 55+ years, cf. 76% 35–54 years, 67% 18–34 years).

Females are much more likely to cite potential problems like loss of trust in the organisation’s information handling practices (57%, cf. 48% males), loss of control (57%, cf. 48% males), psychological harm, such as stress or anxiety (50%, cf. 38% males), feeling disempowered (33%, cf. 23% males) and physical harm (23%, cf. 15% males).

For Australians who have not recently had their personal information mishandled, there is an inflated expectation that a privacy breach is likely to result in identity theft (77% perceived harm, cf. 19% harm experienced) and economic harm (59% perceived harm, cf. 13% harm experienced).

An increase in scams, spam texts or emails was most likely to be experienced and the second highest perceived harm (72% perceived harm, cf. 55% harm experienced).

Figure 40: Harms Australians perceive could result from a privacy breach

P7. Which of the following do you think could result from a problem with how your personal information was handled by an organisation? Select all that apply. Base: Australians who haven’t experienced a problem with how their personal information was handled by an organisation (n=1,086)

Data breaches

A data breach is a type of privacy breach that occurs when personal information held by an organisation is accessed or disclosed without authorisation, or is lost. Data breaches may result from malicious actors, human error or errors in business or technology processes.

Awareness and impact of data breaches

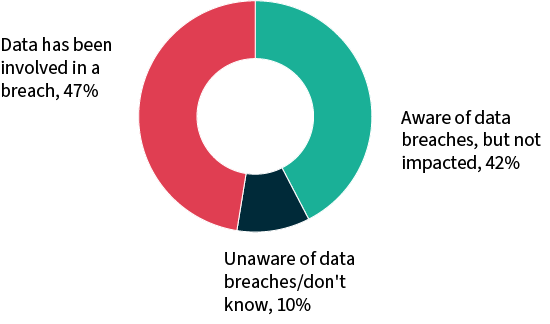

The majority (90%) of Australians were aware of data breaches occurring in Australia in the 12 months prior to completing the survey.

Almost half (47%) said they had been told by an organisation that their data was involved in a data breach in the prior year. A similar proportion (51%) know someone who was affected by a data breach in the same period.

Figure 41: Awareness and impact of data breaches

P9. Are you aware of any data breaches occurring in Australia in the last 12 months?

P10. In the past 12 months, has an organisation told you that your information was involved in a data breach?

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626

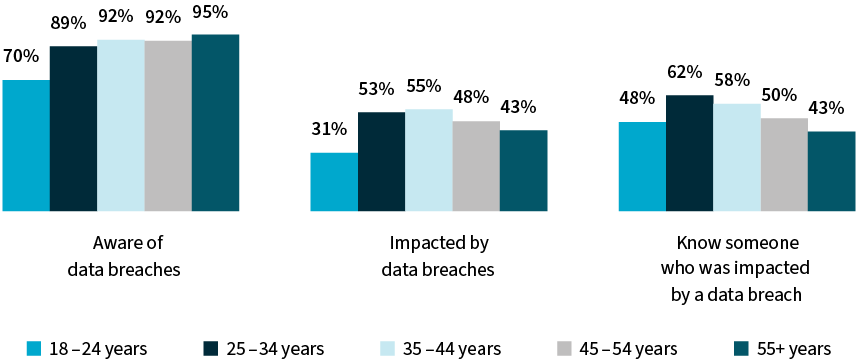

Awareness of data breaches is much higher among older Australians compared to the youngest age group (95% awareness 55+ years, cf. 70% 18–24 years). However, the age group most likely to be impacted directly by a data breach was Australians aged 25 to 44 (54%, cf. 43% 55+ years).

Figure 42: Awareness and impact of data breaches by age

P9. Are you aware of any data breaches occurring in Australia in the last 12 months?

P10. In the past 12 months, has an organisation told you that your information was involved in a data breach?

P11. Was someone you know affected by a data breach in the last 12 months?

Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

Harms experienced from data breaches

Three-quarters (76%) of Australians whose data was involved in a breach said they experienced harm as a result.

More than half (52%) of Australians whose data was compromised in a breach reported an increase in scams, spam texts or emails. This is consistent with the experiences of those whose data was involved in a privacy breach.

Around 1 in 10 experienced significant issues such as emotional or psychological harm (12%), financial or credit fraud (11%) or identity theft (10%).

Figure 43: Harms experienced from data breaches

P12. Which, if any, of the following have you personally experienced because of a data breach of an organisation? Select all that apply. Base: Australians whose information was involved in a data breach (n=760)

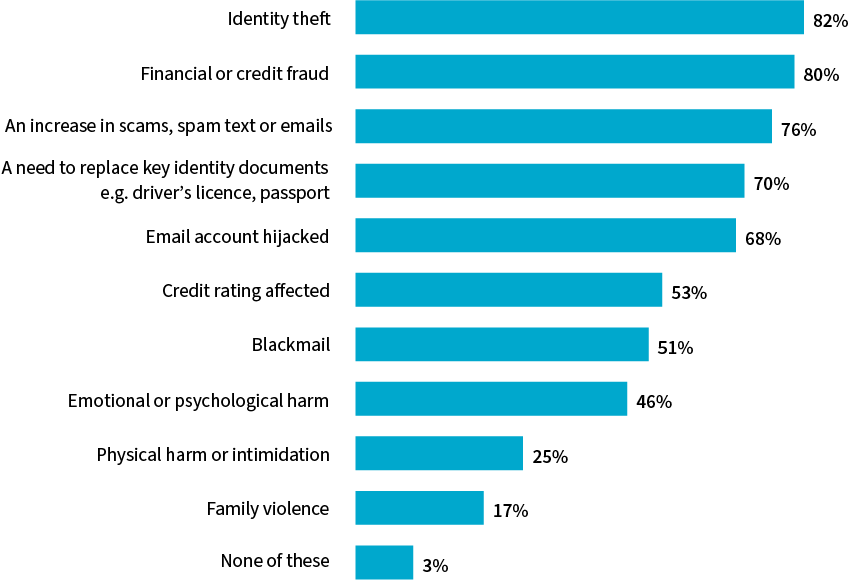

Harms Australians perceive could result from a data breach

Four in five people who have not been affected by a data breach believe identity theft (82%) or financial or credit fraud (80%) could result from such a breach.

Australians aged 18 to 34 are much less likely than those aged 35 and over to think identity theft (70% 18–34 years, cf. 88% 35+ years) or financial or credit fraud (70% 18–34 years, cf. 85% 35+ years) could result from a data breach.

As with privacy breaches, the harms experienced from a data breach are different to the harms people think could result. The expectations are similar in that they often focus on identity theft and financial fraud.

Figure 44: Harms Australians perceive could result from a data breach

P13. Which of the following do you think could result from a data breach of an organisation? Select all that apply. Base: Australians who haven’t had personal information involved in a data breach (n=866)

Reactions to data breaches

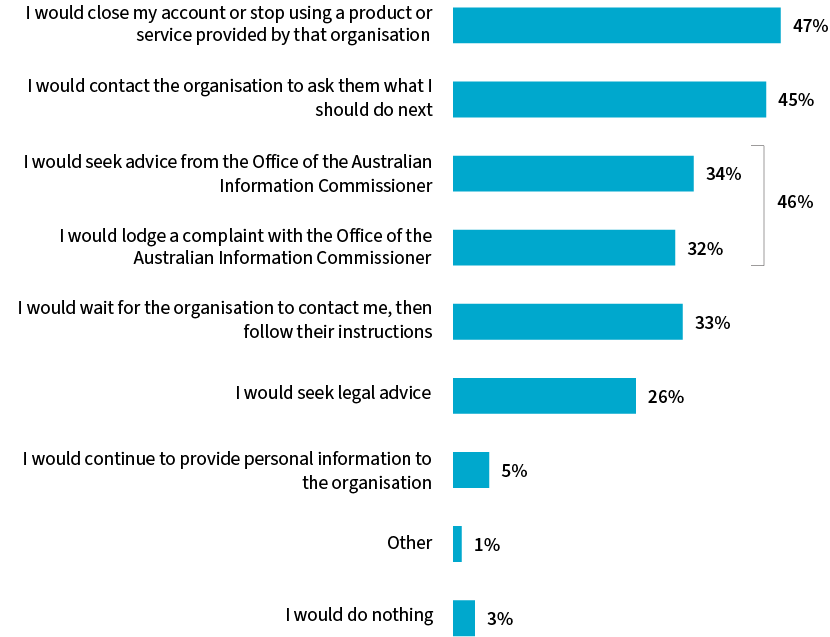

Nearly half (47%) of Australians would close their account or stop using a product or service provided by an organisation that experienced a data breach, 45% would contact the organisation to ask them what to do next and a third (33%) would wait for the organisation to contact them, then follow their instructions.

Almost half (46%) of Australians say they would either seek advice from or lodge a complaint with the OAIC in the event of a data breach. This is driven by those aged 65 and over (55% 65+ years, cf. 44% 18–64 years).

However, this measure should be viewed in the context of completing the online survey, which had earlier probed awareness of the OAIC as an organisation that ‘exists to uphold privacy laws and to investigate complaints about the misuse of personal information’. This creates a situation where respondents have been educated while completing the survey, highlighted within the group of respondents who were previously unaware of the OAIC, of whom 42% now state they would seek advice from or lodge a complaint with the OAIC in the event of a data breach.

Figure 45: Reactions to a data breach

P14. How would you react if your personal information was involved in a data breach of an organisation? Select all that apply. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

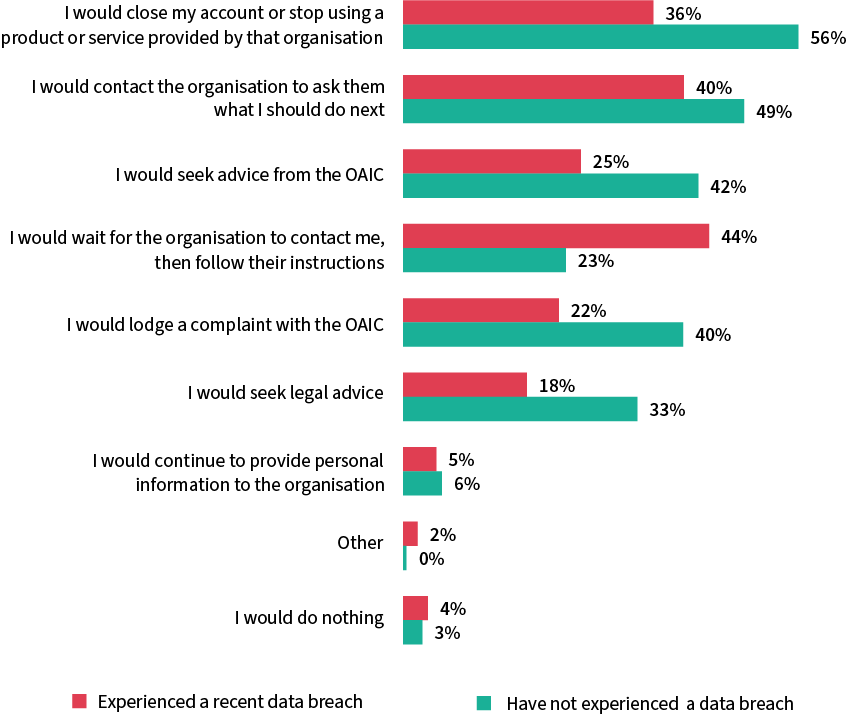

These views vary for people who have experienced a data breach compared to those who have not.

Australians who have experienced a data breach are most likely to say they would wait for the organisation to contact them and follow their instructions (44% experienced a data breach, cf. 23% not experienced a data breach).

People who have not experienced a data breach are most likely to report they would stop using the organisation’s product or service (56% not experienced a data breach, cf. 36% experienced a data breach).

Figure 46: Reactions to a data breach by experience of data breach

P14. How would you react if your personal information was involved in a data breach of an organisation? Select all that apply. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

P10. In the past 12 months, has an organisation told you that your information was involved in a data breach?

Base: Australians 18+ years, experienced a data breach in the previous 12 month (n=760), did not experience a data breach (n=866)

Factors that influence Australians to remain with organisations

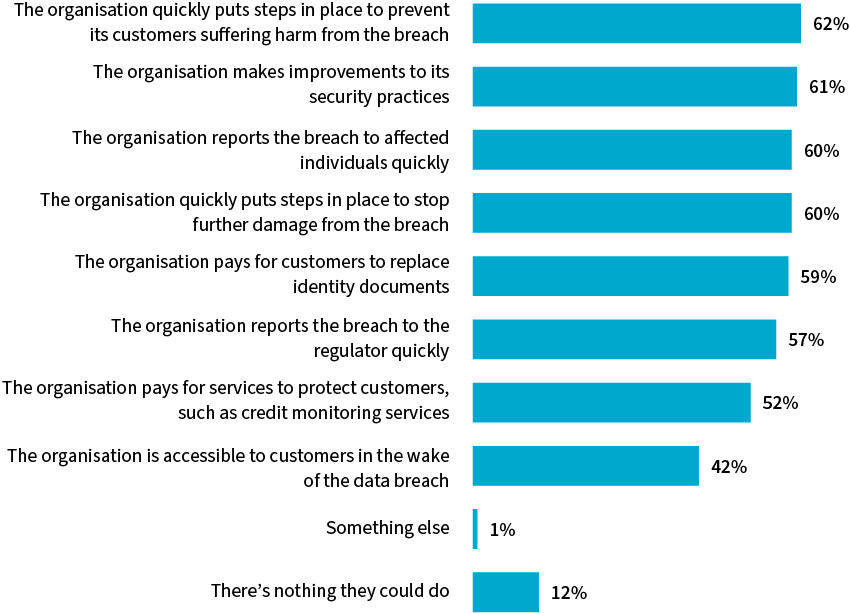

Most Australians are willing to remain with an organisation that has suffered a data breach, provided the organisation quickly takes action.

From a list of 8 factors that may influence an individual to remain with an organisation, respondents on average picked 4 or 5 options.

The actions most likely to influence an individual to remain with an organisation are the organisation quickly putting steps in place to prevent customers experiencing further harm from the breach (62%) and making improvements to its security practices (61%).

For 12% of Australians, there is nothing an organisation could do that would influence them to stay after a data breach.

Figure 47: Factors that influence people to remain with an organisation after a data breach

P15. Which of the following factors would influence you to remain with an organisation that suffered a data breach? Select all that apply. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

Younger Australians are more open to staying with an organisation that takes steps to address a data breach, with only 8% of those aged 18 to 34 saying there is nothing an organisation can do, compared to 15% of people aged 35 and over.

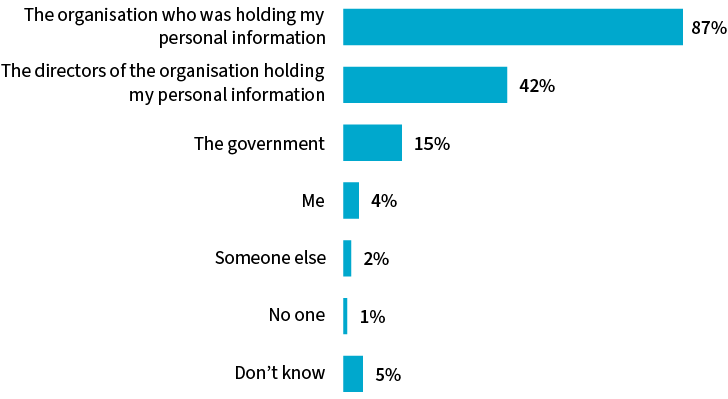

Responsibility for data breaches

The majority (87%) of Australians say organisations should be held responsible if they experience a data breach and individuals’ information is affected.

Two in five (42%) Australians believe the directors of those organisations should be held accountable – this increases to 47% among males, compared to 37% among females.

Figure 48: Responsibility for data breaches

P16. If an organisation that you used was affected by a data breach and your information was affected, who do you think should be held responsible? Select all that apply. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

Australians aged 18 to 24 are less likely to hold organisations accountable, with three-quarters (76%) saying the organisation should be held responsible compared to 88% of those aged 25 and over.

The youngest cohort is more likely to think the government should be held accountable (23% 18–24 years, cf. 14% 25+ years), which is in line with their opinion that the government should be legislating more to protect their privacy.

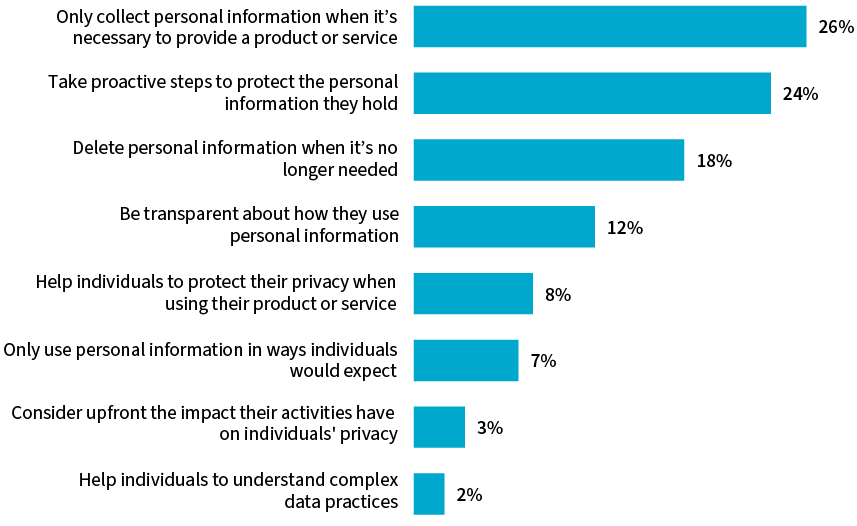

Ways for organisations to protect personal information

A quarter (26%) of Australians believe the most important way an organisation can protect their personal information is by only collecting the information necessary to provide the product or service. Australians view the second most important thing organisations can do is take proactive steps to protect the information they hold (24%).

Figure 49: Most important action organisations should take to protect personal information

P8. There are many ways an organisation can protect your personal information, which of these do you think is the most important? Select one. Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,626)

Part 5: Digital technologies

This section of the report covers biometrics, artificial intelligence and targeted advertising.

Biometric technology

Australians’ level of comfort with biometric information being collected and used depends largely on the type of organisation and the context.

Australians are the most comfortable with the collection and use of their biometric information in border security and law enforcement contexts. There is moderate support for its use by the private sector for safety and security reasons.

The main areas of concern for Australians when it comes to uses of their biometric information are targeting and profiling for commercial purposes, or when the information is needed to access non‑sensitive services like entertainment.

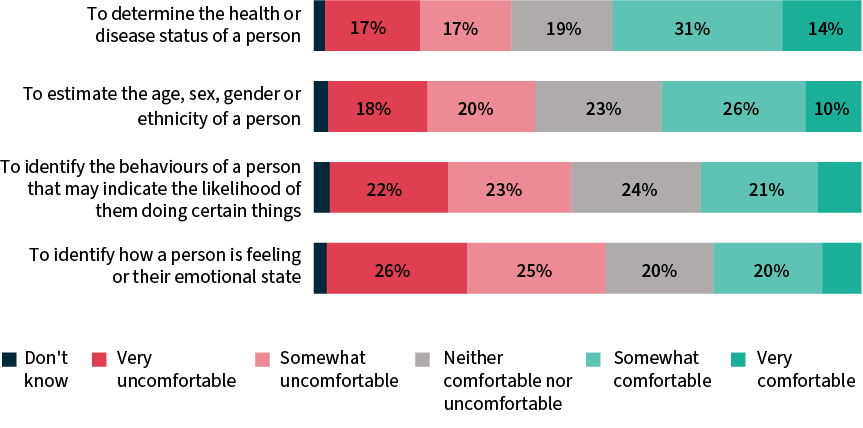

Comfort with biometric analysis

The majority of Australians are not comfortable with biometric analysis, which is defined as the use of a wide variety of techniques, such as AI, to make assumptions or predictions about the characteristics of an individual from their biometric data.

Less than half (45%) are ‘very’ or ‘somewhat comfortable’ with the use of biometric analysis to determine someone’s health or disease status. Australians aged 18 to 34 are the most comfortable with this use of biometric data (56%), compared to 41% for those aged 35 and over.

Australians are divided when it comes to using biometric analysis to estimate a person’s age, sex, gender or ethnicity (36% ‘very’ or ‘somewhat comfortable’, cf. 38% ‘very’ or ‘somewhat uncomfortable’).

Three in ten (29%) Australians are comfortable with biometric analysis being used to predict someone’s behaviour, while 44% are not comfortable.

The use of biometric analysis to identify how a person is feeling or their emotional state has the highest discomfort score (51% uncomfortable, including 26% ‘very uncomfortable’).

Figure 50: Comfort with biometric analysis

B1. Biometric analysis uses a wide variety of techniques, such as artificial intelligence, to make assumptions or predictions about the characteristics of an individual from their biometric data. How comfortable are you with the use of biometric analysis for the following? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

A little more than a third (36%) of Australians aged 18 to 34 are comfortable with biometric analysis being used to predict behaviour, compared to a quarter (26%) of those aged 35 and older.

Comfort with one-to-one uses of biometric information

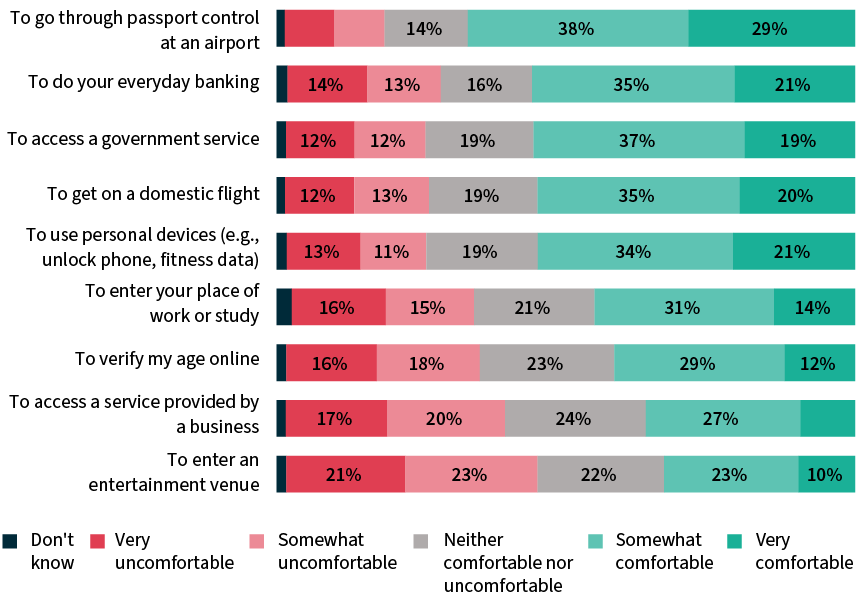

A common use of biometric information is to confirm a person is who they say they are by comparing their biometric information to their existing information. Based on an aggregation of the 9 measures tested, half (49%) of Australians are comfortable with this kind of use of their biometric information.

However, comfort levels vary depending on the organisation and reason for verifying their identification.

Two in three (67%) Australians are comfortable with the use of their biometric information in this way to go through passport control at an airport. More than half are comfortable with its use in the contexts of doing their everyday banking (56%), accessing government services (56%), getting on a domestic flight (55%) and using personal devices, such as to unlock a phone or record fitness data (55%).

Australians are not as comfortable with the use of their biometric information for identity confirmation to access their place of work or study (45%) or verify their age online (42%).

Only a third are comfortable with it being used when they want to access a service provided by a business (36%) or enter an entertainment venue (33%).

Figure 51: Comfort with one-to-one uses of biometric information

B2. A common use of biometric information is to confirm you are who you say you are by comparing it to existing information. How comfortable are you with the use of your biometric information to confirm you are who you say you are in the following situations? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

Comfort with one-to-many uses of biometric information

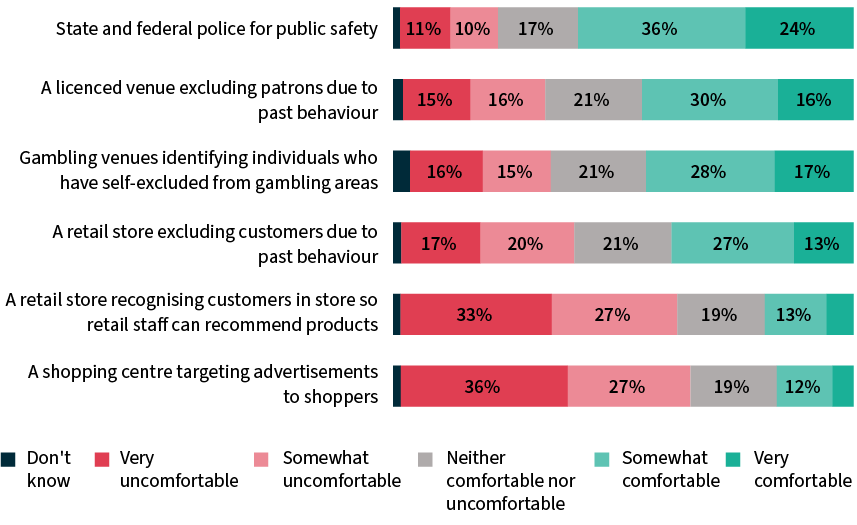

Biometric information can also be used to figure out who a person is by comparing their biometric information to large databases containing many people’s biometric information. In those circumstances, a person’s biometric information may be collected even if they are not the person being identified.

Comfort with this use of biometric information varies significantly depending on the context. There is a reasonable level of comfort with law enforcement using it for public safety, a mixture of opinions around using it to identify people for behavioural-related reasons and discomfort with the commercial use of biometric information in this way.

Australians are most comfortable with their biometric information being used in this way by state and federal police for public safety (60% comfortable, including 24% ‘very comfortable’). This has greater support among Australians aged 55 and older than those aged 18 to 54 (66% 55+ years, cf. 56% 18–54 years).

Nearly half of Australians are comfortable with one-to-many uses of their biometric information by a licenced venue to exclude patrons due to past behaviour (46%) and by gambling venues to identify individuals who have self-excluded from gambling areas (45%).

The majority of Australians are uncomfortable with their biometric information being used by shopping centres for targeted advertising (63% uncomfortable, including 36% ‘very uncomfortable’) and by retail stores to recognise customers in store so staff can recommend products (60% uncomfortable, including 33% ‘very uncomfortable’).

Figure 52: Comfort with one-to-many uses of biometric information

B3. Biometric information can also be used to figure out who a person is by comparing the biometric information to large databases containing many people’s biometric information. Often, your biometric information will be collected even if you are not the person being identified. Sometimes this involves collecting the biometric information of everyone who enters a space, such as a venue, and automatically comparing it to the database. How comfortable are you with the use of your biometric information in the following situations? Base: Australians 18+ years (n=1,653)

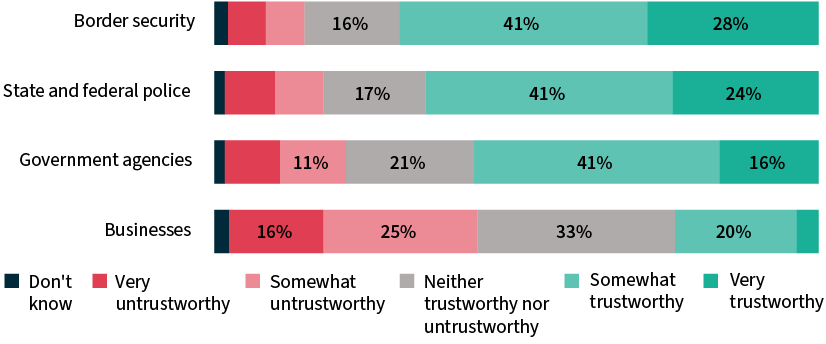

Trust in organisations’ handling of biometric information

Australians are much more likely to trust the public sector to collect and use biometric information than they are businesses.

Seven in ten (69%) Australians consider border security trustworthy, and two-thirds (65%) consider the state and federal police trustworthy.

More than half (57%) of Australians trust government agencies to collect and use biometric information.

Only a quarter (24%) of Australians say businesses are trustworthy when it comes to the collection and use of biometric information.

Figure 53: Trust in organisations’ handling of biometric information

B4. In your opinion, how trustworthy are the following to collect and use biometric information? Base: Australians 18+ (n=1,653)

Australians aged 65 and older are more likely to consider border security (80%) and state and federal police (75%) trustworthy than those aged under 65 (67% border security, 63% state and federal police). Females are also more likely to consider border security (72%) and state and federal police (68%) trustworthy than males (67% border security, 62% state and federal police).

Australians aged 65 and older are more likely than those under 65 to say government agencies are trustworthy (66% 65+ years, 55% 18–64 years).

Australians aged 18 to 34 are more likely to consider businesses trustworthy (30%) compared to people aged 35 and over (21%).

Artificial intelligence

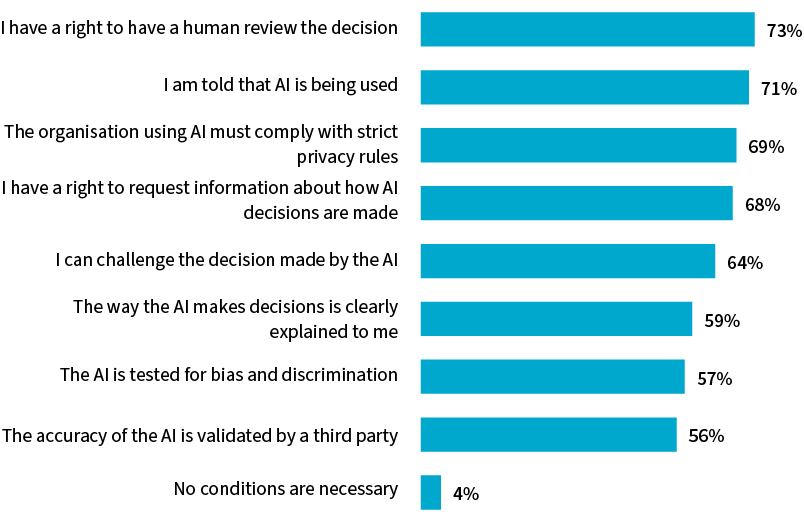

Conditions for the use of artificial intelligence

Australians are cautious about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to make decisions that might affect them, with 96% saying there should be some conditions in place before AI is used in this way.

The conditions considered to be most essential before an organisation uses AI are that people have a right to have a human review the decision (73%) and they are told AI is being used (71%).

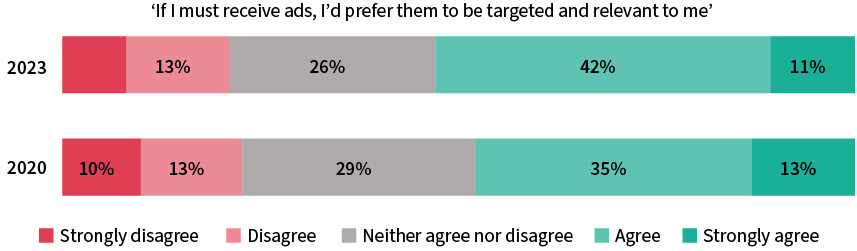

Figure 54: Conditions for the use of artificial intelligence